ServPub

Author: [Author Name]

Publisher: [Publisher Name]

ISBN: [ISBN Number]

Publication Date: [Publication Date]

Edition: [Edition Number, if applicable]

Foreword

Lorem ipsum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed non risus. Suspendisse lectus tortor, dignissim sit amet, adipiscing nec, ultricies sed, dolor. Cras elementum ultrices diam. Maecenas ligula massa, varius a, semper congue, euismod non, mi. Proin porttitor, orci nec nonummy molestie, enim est eleifend mi, non fermentum diam nisl sit amet erat. Duis semper. Duis arcu massa, scelerisque vitae, consequat in, pretium a, enim. Pellentesque congue.

Praesent vitae arcu tempor neque lacinia pretium. Nulla facilisi. Aenean nec eros. Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Suspendisse sollicitudin velit sed leo. Ut pharetra augue nec augue.

Fusce euismod consequat ante. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer adipiscing elit. Pellentesque sed dolor. Aliquam congue fermentum nisl. Mauris accumsan nulla vel diam.

Table of Contents

Collectivities and Working Methods

Pad for working https://ctp.cc.au.dk/pad/p/servpub_methods

Coordinator: Winnie & Geoff

Contributors: In-grid, CC, Systerserver, Winnie & Geoff, Christian and Pablo

What does it mean to publish? Publishing is the act of sharing and passing on knowledge, creating a dynamic relationship between authors/writers/producers and readers. It makes space for others to tune in a particular theme or topic, shaped by a specific medium, format, approach, structure and content. At its core, publishing is inherently a social and political process—it builds communities, invites action, and inspires new ways of thinking. To put simply, publishing means making something public, but in this apparently simple act, there’s a lot at stake, not simply what we publish, but how we publish. The process involves mindful and reflexive thinking of resources, tools, people, technology and infrastructures. In other words, publishing also entails recognizing the post-digital landscape and understanding the political and economic forces that shape that practice.

This book is an intervention in these ongoing debates, emerging out of a particular history and practice of experimental publishing[1]and shaped by the collaborative efforts of various art-tech collectives, operating both within and beyond academic contexts, who are all invested in how to make things public and find ways to publish outside of commercial and institutional norms.[2]. Crucially, the ethics of Free/Libre and Open Source Software (FLOSS), in particular emphasis on the freedom to study, modify and share, operate as core principlesfor this book, enabling modification and versioning with a broader community in mind.[3] What links these traditions is the need to address the social relations that experimental publishing can help to expose and activate differently.[4]

Our working premise is that despite the widespread adoption of open access principles,[5] relatively little has really changed in academic publishing and scholars still distribute their work through paywall enclosures, and follow a production model that is largely unchanged since industrialism. This book is an attempt to draw attention to these historical and material conditions for the production and distribution of books, and to strengthen the possibility of working alternatives.[6] Our concern is that books, and academic books in particular, follow a model of production that belies their criticality. By criticality, we mean to go beyond a criticism of conventional publishing and acknowledge the ways in which we are implicated at all levels in political choices when we engage in how to publish books. It's this kind of reflexivity that has guided our approach. In summary, the book you are now reading is both a book about making and publishing a book, and a kind of manual for thinking and creating one. It seeks to acknowledge and register its own process of coming into being as a book — an onto-epistemological object, if you will. It highlights the interconnectedness of its contents and the form through which it has been created.

Background

The reflexive, collaborative, and experimental forms of publishing underscore our approach to creating this book, and highlight its processual nature [7] and challenge the convention of treating books as if they were discrete objects. Such an approach necessitates thinking beyond standarized platforms, normalized tools, and linear workflows in book publishing and calling upon previous projects and collaborations, including, for instance, Aesthetic Programming in which the authors developed a book about software as if it were software.[8] In FLOSS culture, more than one programmer contributes to writing and documenting code. Contributors might be unknown and are able to update or improve the software by forking — making changes and submitting merge requests to incorporate updates — in which the software is built together as part of a community. To merge, in this sense, is to agree to make a change, to approve it as part of a process of collective decision-making and with mutual trust. This is common practice in software development particularly in the case of FLOSS in which developers place versions of their programs in version control repositories (such as GitLab) so that others can download, clone, and fork them.[9] We were curious to explore how the concept of forking in software practice might inspire new practices of writing by offering all contents as an open resource on a git repository, with an open invitation for other researchers to fork a copy and customize their own versions of the book, with different references, examples, reflections and new chapters open for further modification and re-use. By encouraging new versions to be produced by others, the book set out to challenge publishing conventions and make effective use of the technical infrastructures through which we make ideas public. Clearly wider infrastructures are especially important to understand how alternatives emerge from the need to configure and maintain more sustainable and equitable networks for publishing.

link=File:Rosa2022.jpg|frameless

It is with this in mind that we have tried to engage more fully with the politics of infrastructure that not only supports alternative but also intersectional and feminist forms of publishing. A key inspirational project for this book is "A Transversal Network of Feminist Servers" (ATNOFS) [10]which involved six collectives: Varia (Rotterdam), Hypha (Bycharaest), LURK (Rotterdam), esc mkl (Graz), FHM (Athens) and Constant (Brussels), [11]. The project explores self-hosting infrastructural practices that addresses questions of autonomy and community in relation to technology. Specifically, rosa, is a feminist server, was collaboratively created as part of the project. It serves as a travelling infrastructure for documentation, collective note taking, and publishing to connect people and create relations. I was fortunate enough to be invited to their last event, hosted by Constant in 2022 and sponsored by FHM, where I experienced the workflow, discussions, and collaborative working environments, and saw a physical rosa that enabled me to engage technology differently:

we’ve been calling rosa ‘they’ to think in multiples instead of one determined thing / person. We want to rethink how we want to relate to rosa. (2024)

Trying to get access to the server when you arrive is always a difficult moment, this led to the audio experiment on rosa. We were wondering why it is always so hard to get access to a server? It was only at the end of the last day that it became playful. We needed another day… ALSO: “It feels like rosa always needs a re-introduction.” (2024, 160)

In this way we would argue that the project responds to the pressing need for publishing to acknowledge its broader apparatus.

[to be continued...]

Socio-technical form

An important principle is not to valorize free and open-source software but to stress how technological and social forms come together, and to encourage reflection on shared organizational processes and social relations. This is what Stevphen Shukaitis and Joanna Figiel have previously clarified in "Publishing to Find Comrades," a neat phrase which they borrow from Andre Breton: “The openness of open publishing is thus not to be found with the properties of digital tools and methods, whether new or otherwise, but in how those tools are taken up and utilized within various social milieus."[12] Their emphasis is not to publish pre-existing knowledge and communicate this to a fixed reader — as is the case with much academic publishing — but to work towards developing social conditions for the co-production of meaning. As they express it, "publishing is not something that occurs at the end of a process of thought, a bringing forth of artistic and intellectual labor, but rather establishes a social process where this may further develop and unfold".[13]

That one publishes to establish new social relations aligns with what Fred Moten and Stefano Harney have described as the "logisticality of the undercommons",[14] in contrast to the proliferation of capitalist logics exercised through the management of pedagogy and research publishing. The publishing project of Minor Compositions follows such an approach, perhaps unsurprisingly so, as the publisher of Moten and Harney's work (and our book of course) and the involvement of Stevphen Shukaitis who has coordinated and edited Minor Compositions since its inception in 2009 as an imprint of Autonomedia. In an interview published on their website, explicit connection is made to avant-garde aesthetics but also autonomist thinking and practice, which builds on the notion of collective intelligence, or what Marx referred to, in "Fragment on Machines", as general (or mass) intellect.[15] General intellect is a useful reference as it describes the coming together of technological expertise and social intellect, or general social knowledge, and although the introduction of machine under capitalism broadly oppress workers, they also offer potential liberation from these conditions. Something similar can be argued in the case of publishing, extending its potential beyond the functionary role to make books and generate surplus value for publishers, and instead engage with how thinking is developed with others as part of social relations. To quote from the interview, "not from a position of ‘producer consciousness’ ('we’re a publisher, we make books') but rather from a position of protagonist consciousness ('we make books because it is part of participating in social movement and struggle')."[16] We'd like to think that our book is similarly motivated, not to just publish our work or develop academic careers or generate value for publishers or Universities, but to exert more autonomy over the publishing process and engage more fully with publishing infrastructures that operate under specific socio-technical conditions.

Research content/form

The naming of 'minor compositions' resonates with this, alluding to Deleuze and Guattari's book on Kafka, the subtitle of which is "Towards a Minor Literature".[17] We have previously used this reference for our 'minor tech' workshop, held at transmediale in Berlin in 2023,[18] to question 'big tech' and to follow the three main characteristics identified in Deleuze and Guattari's essay, namely deterritorialization, political immediacy, and collective value. As well as exploring our shared interests and understanding of minor tech in terms of content, the approach was to implement these political principles in practice. This approach maps onto our book project well and its insistence on small scale production, as well as the use of the servpub infrastructure to prepare the publications that came out of the workshop and the shared principle to challenge the divisions of labour and workflows associated with academic publishing.

There's a longer history of these collaborative workshops co-organised by the Digital Aesthetics Research Center at Aarhus University and transmediale festival for art and digital culture based in Berlin. Since 2012, yearly workshops have attempted to make interventions how research is conducted and made public.[19] In brief, an annual open call is released based loosely on the festival theme of that year, targeting researchers from different positionalities and diverse geographical spread. All accepted participants are asked to share a short essay of 1000 words, and upload it to a wiki, and respond online using a linked pad, as well as in person at a research workshop, at which they offer feedback and reduce their texts to 500 words for publication in a “newspaper” that is presented and launched at the festival. Lastly, the participants are invited to submit full length articles of approximately 5000 words for the online open access journal APRJA.[20] The down/up scaling of the text is part of the pedagogy, condensing the argument to identify key arguments and then expanding it once more to substantiate claims. The final stage of the review process ensures that all articles adhere to conventional academic standards for scholarship such as double-blind review.

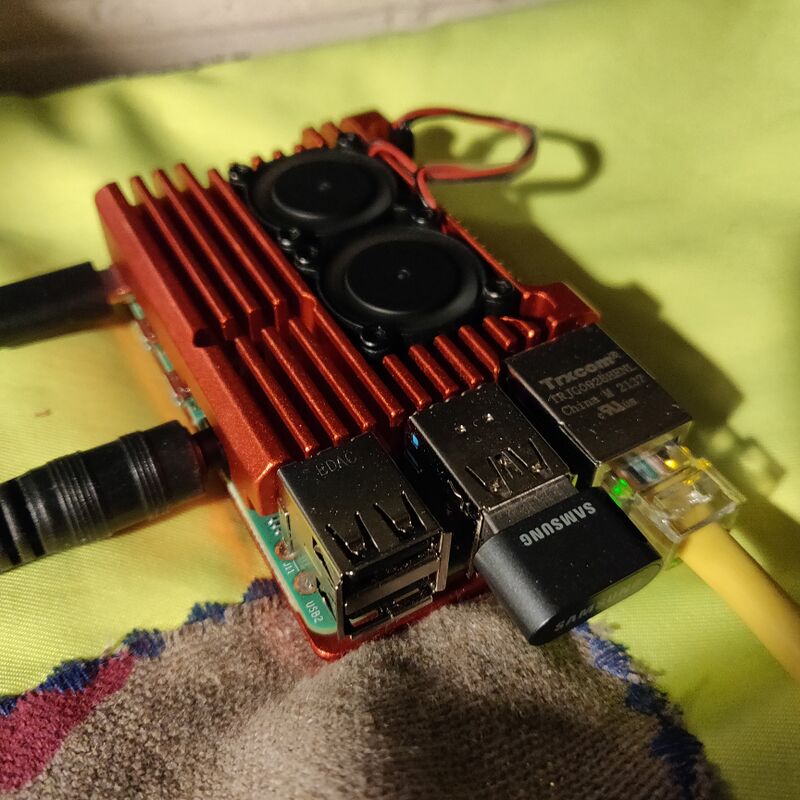

Workshop participants are encouraged to not only engage with research questions and offer critical feedback to each other, through an embodied peer review process, but also with the conditions for producing and disseminating their research. As already mentioned, Minor Tech in 2023 made this explicit, setting out to address alternatives to major (or big) tech by drawing attention to the institutional hosting, both in person and online.[21] In this way, the publishing platform developed for the workshop and its publications can be understood to take on a pedagogic function allowing for an iterative approach to thinking and learning together as part of a network of connected socio-technical organisational practices. The 2024 workshop Content/Form, further developed this approach using small, cheap, portable (raspberry pi) computers that acted as a server and ran the wiki-to-print software to exert more autonomy and to stress the material conditions.[22] Both technological and social forms are brought together as part of an affective infrastructure for collective research.

In contrast to the approaches to research described above, it remains an oddity that academic books in the arts and humanities are still predominantly produced as fixed objects written by individual authors and traditional publishers.[23] Experimental practices such as the ones described so far expand upon the processual character of research, and incorporate practices such as collaborative authorship, community peer review and annotation, updating and iterative processes of developing a set of versions over time, thus offering “an opportunity to reflect critically on the way the research and publishing workflow is currently (teleologically and hierarchically) set up, and how it has been fully integrated within certain institutional and commercial settings.”[24] An iterative approach allows for other possibilities that draw publishing and research closer together, and withing which the divisions of labor between writers, editors, designers, software developers are brought closer together in ways in a non-linear publishing workflow where form and content unfold at the same time, allowing one to shape the other. Put simply, our point is that by focussing on experimental publishing activities, the sharing of resources, modification of texts and versioning, other possibilities emerge for research practice that break out of old models constituted by tired academic procedures (and tired academics) that assume knowledge to be produced and imparted in particular ways. Clearly the tools and practices we use for our writing shape collaborative content.

book structure:

The book charts the development of a bespoke publishing infrastructure that draws together previously separated processes such as writing, editing, peer review, design, print, distribution. Each chapter unpacks practical steps alongside a discussion of some of the poltical implications of our approach.

[go on to describe each chapter in detail]

collectivities

- short semi-structured interviews with each collective

.......0. What characterizes your collective as collective?

.......1. What are your approaches in working together as a group and working with others?

.......2. How does your group work with infrastructure?

.......3. What do you want to work on Servpub?

.......4. How do social relations become transformed?

[minor composition]

Methods

Feminist, intersectionality, queer, radical referencing

doing and making and thinking

development of tools perhaps too

artistic practice/research/artivist approach

end chapter with idea of Book as reflexive practice - reiteratung this point - book about its own making.

Platform infrastructure

Coordinator: In-grid (Katie)

Contributors: Winnie, Becky, Batool, Katie

Wiki4print, the raspberry pi which hosts https://wiki4print.servpub.net/ travels with us. We have constructed our network of servers in such a way that we can keep it's hardware by our side as we use it, teach with it and share it with others. This chapter will consider the materiality of our particular network of nodes, our reasoning for arranging our infrastructure in this way and what it means to move through the world with these objects. By considering our movement from one place to another we can begin to understand how an ambulent server allows us to locate the boundaries of the software processes, the idiosyncrachies of hardware and estates issues, and how we fit into larger networked infrastructures. How we manage departures, arrivals, and points of transcience, reveals boundaries of access, permission, visibility, precarity and luck.

In this chapter we will explain our decision to arrange our physical infrastructure in this way; mobile and in view. To do this we will map our collective experiences in a series of types of space. These spaces are reflective of our relative positions as artist*technologist*activist*academic (delete as appropriate):

* EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS

* DOMESTIC SPACES

* CULTURAL SPACES

* INBETWEENS: BORDERS/TRAVEL

More complete sections of this section will be shared on this page, but you can watch us draft sections of this chapter here: https://pad.riseup.net/p/PlatformInfrastructure-keep

SECTION DRAFTING [WHY PI?]

- By bringing the pi in person to teaching moments, it allowed us to discuss ideas around the physicality of and physical caring for a server. There is trust and intimacy in proximity.

- Legible at borders - recognisable by border patrol officers

- Why the pi and not another single board computer

- Why pre owned/borrowed hardware

SECTION DRAFTING [Cultural spaces]

During it's existence in it's current state, Wiki4Print has been a physical presence at several public workshops and interventions. Although in many (if not all) cases, it would be more practical to leave the hardware at home, we opt to bring it with us. By dint of our artist*sysadmin*academic situations, this has included what we are calling cultural spaces. We are using this to describe spaces which primarily support or present the work of creative practicioners and their work: museums, galleries, artist studios, libraries.

As with our entrances and exits from institutional spaces (universities), domestic locations and moments traveling we need to spend some time feeling out the local situation, and the idiosyncracies of space. Not all two cultural spaces are built the same

We'll tell you about two spaces to explain what we mean.

1. An Artist run space, studio, meanwhile use, precarious

2. Public institution, museum, gallery

* Estates issues: ethernet ports, working plugs, access to extensions, locked doors, opening hours, previous bookings, cleaning regimens, central heating (or lack there of), security (theft), furniture.

* Shitty wifi, privacy

Coordinator: SysterServer

Contributors: xm (ooooo) and Mara

https://digitalcare.noho.st/pad/p/servpub

https://eth.leverburns.blue/p/servpub-2b

Index/Structure

positionality of feminist servers:

- data infrastructure literacy

- digital solidarity networks

- dependencies - alliancies - affinities

- troubleshooting /debugging vulgar marxism

politics of networks

- systerserver networking: internes/alliances/systerserver /....

- lan/wan/vlan

- regulatory bodies ICAN-RFC's develop/discuss standards (missing)

- routing / subnetting (missing)

- history of VPN

- proxy, tor as tools for accessing the web (missing)

- geolocation and network infrastructures

resources matter

- traffic costs and electricity (missing)

Chapter

positionality of feminist servers

In this chapter we will appropriate the tactics of Queercore: How To Punk A Revolution and introduce our feminist server's activities as a catalyst to push techno-feminism into existence and announce we are here to stay. The documentary explores the rise of the queercore cultural and social movement in the mid-1980s, which channeled punk angst into a biting critique of societal homophobia.

We as part of Systerserver and co-dependent on other feminist server projects (Anarchserver, Maadix, leverburns, digiticalcare...), will share ways of doing, tools & strategies to overcome/overthrow the monocultural, centralized oligopolic surveillance & technologies of control.

A server is a place where our data is hosted, the contents of our websites, where we are chatting, storing our stories and imaginaries and access the multiple online services we need to get organized (mailinglists, calendars, notes,...). We don't want to be served, we think a feminist server as an (online) space that we need to inhabit. As inhabitants, we contribute by nurturing a safe space and a place for creativity, experimentation and justice, a place for hacking heteronormativity and patriarchy. Feminist servers have the potential to learn together, to maintain and care for a space together in a non-hierarchical way, and in a non-meritocratic way.

To be able to setup server's we need to have hardware, a machine - a single board computer (like raspberry pi, olimex, an old refurbished laptop,...) or a server in a rack in a data center, a virtual machine (vps), and the will to self host (described in chapter 1). As Systerserver, our feminist server project, we relate and organize around these servers by adopting different roles, defined in conversations in Anarchaserver. [roles]

Besides from these roles we need to encourage “data infrastructure literacy” for the ability to account for, intervene around and participate in the wider socio-technical infrastructures through which data is created, stored and analyzed. Our intent is to make space for collective inquiry, experimentation, imagination and intervention around data. Data as in binary information, suitable for processing by computers, recognizing it's intrinsic (human)labour conditions, maintenance and hence care. In becoming more literate, we cultivate our sensibilities around data politics and as well engage a wider public with digital data infrastructures.

For this reason we need to make servers visible and physical as a crucial/critical space, we need a room of our own and we need a ‘connected room’ of our own.* or a network of one's own

- *(Spideralex) https://creatingcommons.zhdk.ch/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Transcript-Femkespider.pdf.

- *referring to the paranodal periodic publication and series of events and worksession in rotterdam revisting of Virgina Woolf's classic eesay.

By making infrastructures visible with the aid of drawings, diagrams, manuals, metaphors, performances, gatherings, systerserver traverses technical knowledge with an aim to de-cloud (Hilfling Ritasdatter, Gansing, 2024) our data, and redistribute our networks of machines and humans/species.

- ( public interface anarchaserver /calafou: https://zoiahorn.anarchaserver.org/physical-process/ )

- ( are being served - home is a server - https://areyoubeingserved.constantvzw.org/Home_server.xhtml )

A connected room, network of one's own, with allies as co-dependencies, attributes collectivities interacting as radical references which evades hierarchies of cognitive capital based on individuals and underlines the collective efforts to resist within the hegemonic technological paradigm.

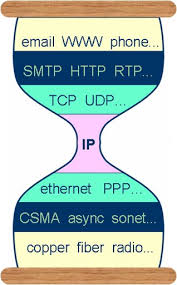

politics of networks

Being part of the Internet, or internets, is a combination of vast, complex and opaque technologies. In this section we look at the technicalities of the Internet, such as IP address, Local, private and virtual networks, routing and subnetting and the politics of scarcity, economy and institutional control.

systerserver networking

The software Tinc functions with (private) networks, and in our public facing server, jean, we configured two named as internes and alliances. While the first is for our backup and etherpad servers, the latter is for some local servers fron our community. And there is the network systerserver as our first attempt to install and configure Tinc. The servers that are connected to these networks are home based with usually dynamic Ips that change. Hence for these servers to be accessible in the Internet they need a fixed (or static) IP. With the creation of the Tinc networks, these servers are accessed via the IP of jean which is a fixed IP. Tinc (and other VPN) tunnels operate within private networks (10.0.0.0), and the machines inside these tunnels can connect to each other with the private IP’s that we assign within these private networks. In that case, we as system admininistators of jean and their allied servers, we have the agency to configure these private networks without the necessity to be given a fixed IP by the internet providers, which most often is an expensive service.

lan/wan/van

To understand somehow more the private and public IP’s and networks, we can look at them from their naming conventions. LAN is an abbreviation for LOCAL AREA NETWORK, and the reserved addresses for these networks are either 192.x.x.x, 169.x.x.x (DHCP) and 172.x.x.x. These addresses are distributed within one room, building that has a router. The router that broadcasts the WiFi or provides ethernet cable connections is the interface between the local network inside the room, and the WAN (WIDER ARE NETWORK), basically the Internet.

The addresses 10.x.x.x are reserved for the private networks, that are also called virtual. Since Virtual Private Networks are more complex to comprehend, here we want to introduce a little bit of their history, hoping that it will illustrate their purposes and functions more.

history and topology of VPN

After the WWW and http protocol, the question of secure connections became urgent as the ability to connect beyond institutional networks became wider. AT&T Bell Laboratories developed an IP Encryption Protocol (SwIPe), implementing encryption in the IP layer. This innovation had a significant influence on the development of IPsec, an encryption protocol that remains in widespread use today.

"IPsec, introduced around the mid-1990s, provided end-to-end security at the IP layer, authenticating and encrypting each IP packet in data traffic. Notably, IPsec was compatible with IPv4 and later incorporated as a core component of IPv6. This technology set the stage for modern VPN methodologies." ref https://www.paloaltonetworks.com/cyberpedia/history-of-vpn

By end of 90s Microsoft worked towards implementing a secure tunnel protocol, creating a virtual data tunnel to ensure more secure data transmission over the web. The encryption methods used in the PPPP was vulnerable to advanced cryptographic attacks. the MPPE (Microsoft Point-to-Point Encryption), only offers up to 128-bit keys which have been deemed insufficient for protecting against advanced threats. Later together with Cisco, they developed another protocol, the L2TP, for serving multiple types of internet traffic.

"L2TP (Layer 2 Tunneling Protocol) works by encapsulating data packets within a tunnel over a network. Since the protocol does not inherently encrypt data, it relies on IPsec (Internet Protocol Security) for confidentiality, integrity, and authentication of the data packets traversing the tunnel." ref https://www.paloaltonetworks.com/cyberpedia/what-is-l2tp

A later tunneling protocol is the openVPN, which has been designed as a more flexible protocol allowing port configuration, and more security.

Tinc protocol follows here...

the drawing of encapsulation from tunnel up/down

While https is another way to secure traffic over the internet, it is distingue from IPSec in that IPsec secures all data traffic within an IP network, suitable for site-to-site connectivity. HTTPS, the secure version of HTTP, using SSL, and its successor TLS secures individual web sessions, typically used for secure remote access to specific applications via the internet.

geolocation and network infrastructures

Now that hopefully we have a clearer idea of the local/private networks vs the public networks aka Internet, it’s important to dive into the distribution of addresses and the politics that stem from this. According an online article about the state of the Internet as of 2023, several factors have contributed to the decline in IPv4:

• Market Saturation: The Internet may have reached a point where there is no additional demand to drive further growth, leading to a natural plateau in IPv4 usage.

• Shift to Content Distribution Networks (CDNs): The transition to CDNs for digital services has reduced the demand for traditional content distribution methods, impacting IPv4 growth.

• IPv4 Address Exhaustion: The depletion of available IPv4 addresses has led to the adoption of address-sharing technologies and significant architectural changes in Internet services, further contributing to the decline.

Despite these trends, the article notes that the majority of the Internet user base (slightly under two-thirds as of the end of 2022) still relies exclusively on IPv4. The future trajectory of IPv4 and IPv6 usage remains uncertain, influenced by technical developments, economic factors, and global events, such as pandemics, economic crises and communications technology in different parts of the word. IPv6 adoption is scant in most of Africa, the Middle East, Eastern and Southern Europe, and the western part of Latin America. Due to the market saturation and the smaller pace of network growth (double check) in those regions appears, for the moment, be adequately accommodated in the continued use of IPv4 NATs. This means that ISP can charge higher prices for a declined number of IPv4 and the need for self or community based hosting that relies on static and fixed IPv4s can be obtained through VPN tunnels and reverse proxies, or Tor onions.

ref https://blog.apnic.net/2024/01/09/measuring-bgp-in-2023-have-we-reached-peak-ipv4/

In the art research project A Tour of Suspended Handshakes, artist Cheng Guo physically visits nodes of China’s Great Firewall. Using network diagnostic tools, he identifies the geolocations mapped to IP addresses of these critical gateways, based on data published by other researchers. At times, these geolocations correspond to scientific and academic centers, which seem like plausible sites for gateway infrastructure. Other times, they lead to desolate locations with no apparent technological presence. While Guo acknowledges that some gateways may be hidden or disguised—for example, antennas camouflaged as lamp posts—the primary reason for these discrepancies lies in the redistribution and subnetting of IP addresses, as well as their resale. These factors make it difficult to pinpoint exact geographical locations. Additionally, online IP location tools provide coordinates in the WGS-84 system (the global GPS standard), whereas locations in China must be converted to GCJ-02 (an encrypted Chinese standard). This further complicates geographic identification, as mapping activities have been illegal in mainland China since 2002. In the case of the Great Firewall, the combination of IP redistribution and encrypted coordinates obscures the true locations of its gateways, rendering the firewall a nebulous and elusive system. Similarly, for mobile (ambulant) servers, geolocating individual servers—beyond the main public-facing ones—remains a challenge. However, unlike the Great Firewall, the mobility of such servers is not enforced through top-down government control. This decentralization has the potential to counteract centralized policies and provide a means of circumvention.

ref https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Restrictions_on_geographic_data_in_China

Computational Publishing:

wiki-4-print, Pelican, paged.js, HTML, CSS, web to print production

CC has ideas: MediaWiki, wiki culture and existing/previous wiki printing practices/research + wiki4print as publishing environment

FLOSS Design principles and processes:

Choice of fonts, and design values/ethics/considerations, licensing, questions of openness, and federation, other ways of organising.

Link to pad that is being shared between design and computational publishing chapters. A record of meetings to get familiar with designing with wiki4print.

STRUCTURE:

Intro:

- This chapter is built upon reflections upon writing the technical docs. In that sense its a recursive text, a companion for another text and is written in tandem with us rewriting the technical text <3

- highlighting syntactical/technical lingo,

- eg using the star \* for transfeminist (reference the source)

- explaining the use of technical metaphors

Positioning/argument:

- Contextualise within "standard" doc-writing norms. Engineering work-flows, reliance on docs to standardise practice and erase human nuance, etc. - do we also want to talk about disobedience here? - ref: Geohackers text

- Importance of chainlinking a technical practice in one seemingly neutral spaces (docs) to other, more politically implicated contexts (work, efficiency, transparent methods, etc) - ref: Ahmed?

- Articulate our response to that. How can we offer a response, why? What is the percieved gap we are trying to fill with these proposed docs?

- Who can we reference as guides for this offering. Mentions of action research by other people

- ref. 'filing a bug report on bug reporting', writing technical docs that refelct on techincal docs

Context in servpub project:

- What do tech-docs do, What dont they do - poetic lists? - tell stories?

- How/why did we (in-grid specific) start making these docs?

- - learning through writing and sharing.

- means for getting more in-grid members on board. The project itself was a response to Winnie Soons call for creating a trans\*feminist research project in London. (We don't yet know what makes this one so London: deliberatly working outside of institutions, skimming resources and distrubution skills) - should talk & ask Winnie about that/perspective

- syster using it for other projects Les ask them about these strands!

- What emerged through that process, in terms of needs and processes?

- In depth explainaition of the technical practice (docs), and the social labour relations around it. highlighting where optimisation is prioritised and the industrial tools built around making that practice easy as possible

- learning / teaching? Self-teaching? how are the docs related to this?

Reflection on technical choices:

- short overview and use this refernce the colophon!

- might have or refere to the diagrams of relations

- mention readical referencing and point to colophon

- should mention the technical choices of the docs (not hardware) as that wont be in the colophon

ref:

- "Software does not come withour its world" - Maria Bellacasa quoted in geohackers text

Activating the docs

- Docs become active (used, referenced, relevant) when we the need for building is shared, and others want to expand independant infras.

- "_we are reminded collectively that technical knowledge is not the only knowledge suitable for addressing the situations we find our-selves in_" and yet technical knowledge is what we are trying to spread with docs. (Suchman, Lucy, Human-Machine Reconfigurations: Plans and Situated Actions)

- while we still needed and wanted to keep our docs legible, what are the necessary deviations from the doc-making tradition that we need in order to address our readers, who, decidedly, were not other engineers. How do we write docs DIFFERENTLY but not necessarily more simply. We do not assume the ignorance or simple-mindedness of a non-technically educated (conditioned) readership. How do we write for solidarity?

- docs are for linear processes, breaking linearity was a major challeng you m

- docs assume that you start somewhere and end somewhere, but as we are writing this its evident that we started many times in different places, and ended in many more, and some have not even ended even though that part of the project is technically "done"

- also how we make docs accessible, adding intros that overview and question practices in a way all can engage.

Annotating the Chapter with snippets from the docs

ref: https://time.cozy-cloud.net/

Graceful ending

Side note: dealing with deprecated tools!

References

Pad up to date: https://pad.riseup.net/p/PraxisDoublingChapterNotes-keep

STRUCTURE:

Intro:

- This chapter is built upon reflections upon writing the technical docs. In that sense its a recursive text, a companion for another text and is written in tandem with us rewriting the technical text <3

- highlighting syntactical/technical lingo,

- eg using the star \* for transfeminist (reference the source)

- explaining the use of technical metaphors

Positioning/argument:

- Contextualise within "standard" doc-writing norms. Engineering work-flows, reliance on docs to standardise practice and erase human nuance, etc. - do we also want to talk about disobedience here? - ref: Geohackers text

- Importance of chainlinking a technical practice in one seemingly neutral spaces (docs) to other, more politically implicated contexts (work, efficiency, transparent methods, etc) - ref: Ahmed?

- Articulate our response to that. How can we offer a response, why? What is the percieved gap we are trying to fill with these proposed docs?

- Who can we reference as guides for this offering. Mentions of action research by other people

- ref. 'filing a bug report on bug reporting', writing technical docs that refelct on techincal docs

Context in servpub project:

- What do tech-docs do, What dont they do - poetic lists? - tell stories?

- How/why did we (in-grid specific) start making these docs?

- - learning through writing and sharing.

- means for getting more in-grid members on board. The project itself was a response to Winnie Soons call for creating a trans\*feminist research project in London. (We don't yet know what makes this one so London: deliberatly working outside of institutions, skimming resources and distrubution skills) - should talk & ask Winnie about that/perspective

- syster using it for other projects Les ask them about these strands!

- What emerged through that process, in terms of needs and processes?

- In depth explainaition of the technical practice (docs), and the social labour relations around it. highlighting where optimisation is prioritised and the industrial tools built around making that practice easy as possible

- learning / teaching? Self-teaching? how are the docs related to this?

Reflection on technical choices:

- short overview and use this refernce the colophon!

- might have or refere to the diagrams of relations

- mention readical referencing and point to colophon

- should mention the technical choices of the docs (not hardware) as that wont be in the colophon

ref:

- "Software does not come withour its world" - Maria Bellacasa quoted in geohackers text

Activating the docs

- Docs become active (used, referenced, relevant) when we the need for building is shared, and others want to expand independant infras.

- "_we are reminded collectively that technical knowledge is not the only knowledge suitable for addressing the situations we find our-selves in_" and yet technical knowledge is what we are trying to spread with docs. (Suchman, Lucy, Human-Machine Reconfigurations: Plans and Situated Actions)

- while we still needed and wanted to keep our docs legible, what are the necessary deviations from the doc-making tradition that we need in order to address our readers, who, decidedly, were not other engineers. How do we write docs DIFFERENTLY but not necessarily more simply. We do not assume the ignorance or simple-mindedness of a non-technically educated (conditioned) readership. How do we write for solidarity?

- docs are for linear processes, breaking linearity was a major challeng you m

- docs assume that you start somewhere and end somewhere, but as we are writing this its evident that we started many times in different places, and ended in many more, and some have not even ended even though that part of the project is technically "done"

- also how we make docs accessible, adding intros that overview and question practices in a way all can engage.

Annotating the Chapter with snippets from the docs

ref: https://time.cozy-cloud.net/

Graceful ending

Side note: dealing with deprecated tools!

References

Pad up to date: https://pad.riseup.net/p/PraxisDoublingChapterNotes-keep

{{ :Chapter_4c:_Publishing_%26_Distribution }}

NOTES:

Distribution and computational readings (read/write) // need to make this fit better

Coordinator: Aarhus (Christian & Pablo)

Contributors: Christian & Pablo, Martino/Roel

Autonomous (research) libraries: building collective references (challenging conventional research referencing), and how to position autonomous libraries within larger instititional boundaries. [Pablo/Christian - coord will build a library as part of ServPub (potentially in collaboration with Martino/Roel] (distribution)

+ autonomous library within a non(?)-autonomous (university) platform

+ using the library as part of the coordination/revision/co-writing process (and also writing about this)

the reference list is here: https://wiki4print.servpub.net/index.php?title=References

Infrastructure Colophon

Pad for working https://ctp.cc.au.dk/pad/p/infra_colophon

Coordinator: Winnie & Geoff

Contributors: Everyone

Our book is derived from the larger project ServPub which uses wiki-to-print, a collective publishing environment based on MediaWiki software, Paged Media CSS techniques and the JavaScript library Paged.js, and which renders a preview of the PDF in the browser [1]. It builds on the work of others and wouldn’t be possible without the help of Creative Crowds [2], who themselves acknowledge the longer history which includes: the Diversions publications by Constant and OSP[3]; the book Volumetric Regimes by Possible Bodies and Manetta Berends[4]; TITiPI's wiki-to-pdf environments developed by Martino Morandi[5]; Hackers and Designers' version wiki2print that was produced for the book Making Matters[6]. As such our work is a continuation of a network of instances and interconnected practices that are documented and shareable[7].

Similarly the server infrastructure includes VPN server and static IP which are provided by Systerserver, Free and Open source software Tinc [8], VPN Server provided by Systerserver, Raspberry Pi mobile servers set up by In-grid, Domain registration and DNS management via TuxIC [9] based in the Netherlands.

For our communication and working tools:

- Monthly group meeting and discussion: jitsi, hosted by Greenhost [10];

- Etherpads hosted by riseup [11] and Critical Technical Practice (CTP) server from Aarhus University [12];

- Mailiing list provided by Systerserver;

- Poll system for meeting times by anarchaserver: https://transitional.anarchaserver.org/date/

- Git repository by Systerserver

Notes:

1. https://www.mediawiki.org + https://www.w3.org/TR/css-page-3/ + https://pagedjs.org

3. https://diversions.constantvzw.org + https://constantvzw.org & https://osp.kitchen

4. http://data-browser.net/db08.html + https://volumetricregimes.xyz, see https://possiblebodies.constantvzw.org & https://manettaberends.nl

5. http://titipi.org + https://titipi.org/wiki/index.php/Wiki-to-pdf

6. https://hackersanddesigners.nl + https://github.com/hackersanddesigners/wiki2print + https://hackersanddesigners.nl/s/Publishing/p/Making_Matters._A_Vocabulary_of_Collective_Arts

7. https://git.vvvvvvaria.org/CC/wiki-to-print

8. https://tinc-vpn.org/download/

10. https://meet.greenhost.net/

Bibliography

References

Adema, Janneke. Liquid Books, Cambridge MA: The MIT Press 2021.

Adema, Janneke. "Experimental Publishing as Collective Struggle: Providing Imaginaries for Posthumanist Knowledge Production," Culture Machine 23 (2024). https://culturemachine.net/vol-23-publishing-after-progress/adema-experimental-publishing-collective-struggle/.

Ciston, Sarah, and Mark Marino. "How to Fork a Book: The Radical Transformation of Publishing." Medium, 2021. https://markcmarino.medium.com/how-to-fork-a-book-the-radical-transformation-of-publishing-3e1f4a39a66c.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature [1975], trans. Dana Polan, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1986.

Goriunova, Olga. "Uploading Our Libraries: The Subjects of Art and Knowledge Commons." In Aesthetics of the Commons, edited by Cornelia Sollfrank, Felix Stalder, and Shusha Niederberger, 41–62. Diaphanes, 2021.

Graziano, Valeria, Marcell Mars, and Tomislav Medak. "Learning from #Syllabus." In State Machines: Reflections and Actions at the Edge of Digital Citizenship, Finance, and Art, edited by Yiannis Colakides, Marc Garrett, and Inte Gloerich, 115–28. Institute of Network Cultures, 2019.

Graziano, Valeria, Marcell Mars, and Tomislav Medak. "When Care Needs Piracy: The Case for Disobedience in Struggles Against Imperial Property Regimes." In Radical Sympathy, edited by Brandon LaBelle, 139–56. Errant Bodies Press, 2022.

Harney, Stefano, and Fred Moten. The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study. Wivenhoe/New York/Port Watson: Minor Compositions, 2013.

Kelty, Christopher M. Two Bits: The Cultural Significance of Free Software. Duke University Press, 2020.

Klang, Mathias. "Free software and open source: The freedom debate and its consequences." First Monday (2005). https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/121.

Kolb, Lucie. Sharing Knowledge in the Arts: Creating the Publics-We-Need. Culture Machine 23 (2024): https://culturemachine.net/vol-23-publishing-after-progress/kolb-sharing-knowledge-in-the-arts/.

Mansoux, Aymeric, and Marloes de Valk, Floss + Art. Poitiers: GOTO10 (2008).

Mars, Marcell. "Let’s Share Books." Blog post. January 30, 2011. https://blog.ki.ber.kom.uni.st/lets-share-books.

Mars, Marcell, and Tomislav Medak. "System of a Takedown: Control and De-commodification in the Circuits of Academic Publishing." In Archives, edited by Andrew Lison, Marcell Mars, Tomislav Medak, and Rick Prelinger, 47–68. Meson Press, 2019.

Shukaitis, Stevphen, and Joanna Figiel. "Publishing to Find Comrades: Constructions of temporality and solidarity in autonomous print cultures." Lateral 8(2), 2019. https://doi.org/10.25158/L8.2.3.

Soon, Winnie, and Geoff Cox. Aesthetic Programming. London: Open Humanities Press, 2020.

Sumi, Denise Helene. "On Critical 'Technopolitical Pedagogies': Learning and Knowledge Sharing with Public Library/Memory of the World and syllabus ⦚ Pirate Care." In APRJA 13, forthcoming 2024.

Udall, Julia, Becky Shaw, Tom Payne, Joe Gilmore and Zamira Bush, “An unfinished lexicon for autonomous publishing.” ephemera 20(4), 2021.

Weinmayr, Eva. "One publishes to find comrades." Publishing Manifestos: an international anthology from artists and writers, edited by Michalis Pichler. Cambridge MA: The MIT Press, 2018.

White, Daley. Historical Trends and Growth of OA (2023), https://blog.cabells.com/2023/02/08/strongopen-access-history-20-year-trends-and-projected-future-for-scholarly-publishing-strong/.

- ↑ Janneke Adema, "Experimental Publishing as Collective Struggle: Providing Imaginaries for Posthumanist Knowledge Production", Culture Machine 23 (2024), https://culturemachine.net/vol-23-publishing-after-progress/adema-experimental-publishing-collective-struggle/

- ↑ For example, influential here is the output of the Experimental Publishing master course (XPUB) at Piet Zwart Institute in Rotterdam, where students, guests and staff make 'publications' that extend beyond print media. See: https://www.pzwart.nl/experimental-publishing/special-issues/. Two other grassroot collectives based in the Netherlands, Varia and Hackers & Designers, have also focused on developing free and open source publishing tools, including web-to-print and chat-to-print techniques. See https://varia.zone/en/tag/publishing.html and https://www.hackersanddesigners.nl/experimental-publishing-walk-in-workshop-ndsm-open.html

- ↑ Klang, Mathias. "Free software and open source: The freedom debate and its consequences." First Monday (2005): https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/1211 and Mansoux, Aymeric and de Val, Marloes. 2008. Floss + Art. Poitiers: GOTO10

- ↑ See Christopher M. Kelty, Two Bits: The cultural significance of free software (Duke University Press, 2020), and Lucie Kolb, Sharing Knowledge in the Arts: Creating the Publics-We-Need. Culture Machine 23 (2024): https://culturemachine.net/vol-23-publishing-after-progress/kolb-sharing-knowledge-in-the-arts/.

- ↑ See Daley White, Historical Trends and Growth of OA (2023), https://blog.cabells.com/2023/02/08/strongopen-access-history-20-year-trends-and-projected-future-for-scholarly-publishing-strong/, and Butler, Leigh-Ann, Lisa Matthias, Marc-André Simard, Philippe Mongeon, and Stefanie Haustein. "The oligopoly’s shift to open access: How the big five academic publishers profit from article processing charges." Quantitative Science Studies 4, no. 4 (2023): 778-799, https://direct.mit.edu/qss/article/4/4/778/118070/The-oligopoly-s-shift-to-open-access-How-the-big

- ↑ For example the independent publisher Open Humanities Press, and especially the Liquid and Living Book series edited by Gary Hall and Clare Birchall, publishes experimental digital books under the conditions of both open editing and free content. Also published by OHP, in the Data Browser series, Volumetric Regimes edited by Possible Bodies (Jara Rocha and Femke Snelting) used wiki-to-print development and F/LOSS redesign by Manetta Berends. See http://www.openhumanitiespress.org/books/series/liquid-books/ and http://www.data-browser.net/db08.html

- ↑ See Adema Janneke, Versioning and Iterative Publishing 2021, https://commonplace.knowledgefutures.org/pub/5391oku3/release/1; Adema, Janneke and Kiesewetter, Rebekka. 2022. Experimental Book Publishing: Reinventing Editorial Workflows and Engaging Communities, https://commonplace.knowledgefutures.org/pub/8cj33owo/release/1; Octomode 2023 by Varia and Creative Crowds, https://cc.vvvvvvaria.org/wiki/Octomode; as well as Soon, Winnie, 2024 # Writing a Book As If Writing a Piece of Software, BiblioTech: ReReading the Library

- ↑ Winnie Soon & Geoff Cox, Aesthetic Programming (London: Open Humanities Press, 2021). Link to downloadable PDF and online version can be found at https://aesthetic-programming.net/; and Git repository at https://gitlab.com/aesthetic-programming/book.

- ↑ In response to the invitation to fork a copy, Mark Marino and Sarah Ciston added their chapter 8 and a half (sandwiched between chapters 8 and 9), Sarah Ciston & Mark C. Marino, “How to Fork a Book: The Radical Transformation of Publishing,” Medium, 2021, https://markcmarino.medium.com/how-to-fork-a-book-the-radical-transformation-of-publishing-3e1f4a39a66c. In addition, we consider the book’s translation into Chinese as a fork, on which we have been working closely with Taiwanese art and coding communities, and Taipei Arts Centre. See Shih-yu Hsu, Winnie Soon, Tzu-Tung Lee, Chia-Lin Lee, Geoff Cox, “Collective Translation as Forking (分岔)” Journal of Electronic Publishing 27 (1), pp. 195-221. https://doi.org/10.3998/jep.5377(2024).

- ↑ A Traversal Network of Feminist Servers, available at https://atnofs.constantvzw.org/

- ↑ The ATNOFS project draws upon the Feminist Server Manifesto.Are You Being Served? A Feminist Server Manifesto 0.01. Available at htps://areyoubeingserved.constantvzw.org/Summit_aterlife.xhtm. For a fuller elaboration of Feminist servers, produced as a collective outcome of a Constant meeting in Brussels, December 2013, see https://esc.mur.at/en/werk/feminist-server.

- ↑ Stevphen Shukaitis & Joanna Figiel, "Publishing to Find Comrades: Constructions of Temporality and Solidarity in Autonomous Print Cultures," Lateral 8.2 (2019), https://doi.org/10.25158/L8.2.3. For another use of the prase, see Eva Weinmayr, "One publishes to find comrades," in Publishing Manifestos: an international anthology from artists and writers, edited by Michalis Pichler. Cambridge MA: The MIT Press, 2018.

- ↑ Shukaitis & Figiel

- ↑ Stefano Harney & Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (Wivenhoe/New York/Port Watson: Minor Compositions, 2013).

- ↑ Fragment on Machines is a passge in Karl Marx, Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy (Rough Draft), Penguin Books in association with New Left Review, 1973, available at https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1857/grundrisse/.

- ↑ "About - Minor Compositions," excepted from an interview with AK Press, https://www.minorcompositions.info/?page_id=2.

- ↑ Gilles Deleuze & Félix Guattari, Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature [1975], trans. Dana Polan (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1986).

- ↑ A Peer-Reviewed Journal About Minor Tech 12 (1) (2023), https://aprja.net//issue/view/10332.

- ↑ A full list of these workshops and associated publication can be found at... ADD

- ↑ APRJA, https://aprja.net/

- ↑ Since 2022, newspaper and journal publications have been produced iteratively in collaboration with Simon Browne and Manetta Berends using wiki-to-print tools, based on MediaWiki software, Paged Media CSS techniques and the JavaScript library Paged.js, which renders the PDF.

- ↑ More details on the Content/Form workshop and tools as well as the newspaper publication can be found at https://wiki4print.servpub.net/index.php?title=Content-Form.

- ↑ See Janneke Adema’s “The Processual Book How Can We Move Beyond the Printed Codex?” (2022), LSE blog, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/lsereviewofbooks/2022/01/21/the-processual-book-how-can-we-move-beyond-the-printed-codex/.

- ↑ The Community-led Open Publication Infrastructures for Monographs research project, of which Adema has been part, is an excellent resource in this respect, including a section of Versioning Books from which the quote is taken. See https://compendium.copim.ac.uk/.