No edit summary |

|||

| (84 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

__NOTOC__ | |||

<!-- //////////////////////////////////////////// --> | |||

<div id="cover"> | |||

<div id="cover-title"> | |||

Publishing as Collective Infrastructure</div> | |||

</div> | |||

<div class="page_break"></div> | |||

<!-- //////////////////////////////////////////// --> | <!-- //////////////////////////////////////////// --> | ||

<div id="publication-details-page"> | <div id="publication-details-page"> | ||

{{ :PublicationDetails }} | {{ :PublicationDetails }} | ||

| Line 10: | Line 20: | ||

<!-- //////////////////////////////////////////// --> | <!-- //////////////////////////////////////////// --> | ||

<div id="foreword-page"> | <div id="foreword-page"> | ||

{{ : | {{ :Preface }} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 19: | Line 29: | ||

<div id="index-page"> | <div id="index-page"> | ||

== | == Content Index == | ||

< | <div id="toc"> | ||

* [[#chapter-1|Being Book]] | |||

* [[#chapter-2|Ambulant Infrastructure]] | |||

* [[#chapter-3|Feminist Networking]] | |||

* [[#chapter-4|Designing with wiki4print]] | |||

* [[#chapter-5|Praxis Doubling]] | |||

* [[#chapter-6|Angels of Our Better Infrastructure]] | |||

* [[#chapter-7|Referencing]] | |||

* [[#bibliography|Bibliography]] | |||

* [[#contributors|Contributors]] | |||

<!--* [[#statement|Collective Statement]]--> | |||

* [[#colophon|Colophon]] | |||

</div> | |||

</div> | |||

<!-- //////////////////////////////////////////// --> | |||

<div class="chapter" id="chapter-1"> | |||

{{ :Chapter_1:_Collectivities_and_Methods}} | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class=" | |||

<div class="chapter" id="chapter-2"> | |||

{{ :Chapter_2a:_Server_Issues:_Platform_Infrastructure }} | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

< | <div class="chapter" id="chapter-3"> | ||

{{ :Chapter_2b:_Server_Issues:_Networked_Infrastructure }} | |||

</div> | |||

<div class="chapter" id="chapter- | <div class="chapter" id="chapter-4"> | ||

{{ : | {{ :Chapter_4b:_Public:_FLOSS_Design }} | ||

| Line 44: | Line 80: | ||

<!-- //////////////////////////////////////////// --> | <!-- //////////////////////////////////////////// --> | ||

<div class=" | <div class="chapter" id="chapter-5"> | ||

{{ :Chapter_3:_Praxis_Doubling}} | |||

</div> | |||

<div class="chapter" id="chapter- | <!-- //////////////////////////////////////////// --> | ||

<div class="chapter" id="chapter-6"> | |||

{{ : | {{ :Chapter_4 }} | ||

| Line 55: | Line 98: | ||

<!-- //////////////////////////////////////////// --> | <!-- //////////////////////////////////////////// --> | ||

<div class=" | <div class="chapter" id="chapter-7"> | ||

{{ :Chapter_5b:_Distribution }} | |||

</div> | |||

<div id="bibliography"> | |||

<!-- //////////////////////////////////////////// --> | |||

<div class="chapter" id="bibliography"> | |||

== Bibliography == | == Bibliography == | ||

| Line 63: | Line 114: | ||

<!-- Need to actually include each one's content for each chapter --> | <!-- Need to actually include each one's content for each chapter --> | ||

{{ :Chapter_9 }} | |||

</div> | |||

<div class="chapter" id="contributors"> | |||

== Contributors == | |||

<!-- Need to actually include each one's content for each chapter --> | |||

{{ :Chapter_10 }} | |||

</div> | |||

<!-- //////////////////////////////////////////// --> | |||

<div class="chapter" id="colophon"> | |||

{{ :Chapter_6:_Infrastructure_Colophon }} | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

Latest revision as of 10:14, 9 January 2026

Author: [Author Name]

Publisher: [Publisher Name]

ISBN: [ISBN Number]

Publication Date: [Publication Date]

Edition: [Edition Number, if applicable]

Foregrounding the Social and Affective Life of Open Access Publishing

Experimental Publishing Group (Open Book Futures)

Since 2019, the Copim community – a network of scholars, open access publishers, librarians, infrastructure providers, and others interested in building a more equitable and diverse ecosystem for scholarly publishing – has developed and sustained new infrastructures for open access (OA) book publishing. Through the Community-led Open Publication Infrastructures for Monographs (COPIM) project (2019–2023) and the Open Book Futures (OBF) project (2023–2026), they have created and maintained cooperative organisations, non-for-profit funding models, and decentralised systems that support community-led OA publishing.[1]

As part of this, the OBF Experimental Publishing Group – within a number of experimental book pilot projects – has supported authors, publishers, and developers to experiment with the forms, formats, practices, processes, and relationalities of OA monograph publishing in the humanities beyond single-authored, print-based models.[2]

Besides providing editorial, technical, and conceptual support, during OBF, the Experimental Publishing Group took on a grant-giving role, offering small amounts of funding to three pilot projects selected via an open call, among them "ServPub – An Infrastructure to Serve and Publish" resulting in this book. Crucially, this experiment in funding was itself conceived as part of the research process: The aim was to create space for participating groups to define what was meaningful and relevant to them. Beyond minimal baseline requirements aligned with OBF’s values – such as the use of open-source tools, the implementation of Diamond OA, and open documentation – we prioritised community agency over directing experimentation.[3]

We see this work as important because many scholars lack the support, time, and energy to explore alternative publishing models (within or beyond OA publishing) – even when they are aware of the limitations of prevailing systems and express a desire to work differently.[4] The para-academic and non-academic communities involved in this book face parallel constraints that take the form of precarity, unpaid labour, and chronic infrastructural under-resourcing. In the academic sphere specifically, these pressures are intensified by an environment in which prestige is, as Aileen Fyfe et al.[5] note, increasingly concentrated in the hands of a few large commercial publishers who have expanded and centralised control over editorial systems, peer-review governance, proprietary submission platforms, and citation-based metrics. These components are now marketed to neoliberal research institutions as value-added services promising more efficient management of scholarship. In doing so, they reproduce prestige economies that equate scholarly value with citation counts, journal rankings, and high-volume publishing. Within this entanglement of institutional priorities and commercial publishing agendas, some research institutions, policy providers, and funding bodies have begun embedding specific, funders- and policy-driven versions of OA publishing into frameworks of research evaluation and funding eligibility.[6] In these contexts, openness is enacted as a static, top-down mandate – a compliance checkbox within a bureaucratic apparatus of performance metrics. As a result, mandated forms of OA become directly tied to institutional and individual competitiveness, positioned as a prerequisite for securing funding, increasing visibility, and sustaining advantage within performance-based environments. For many arts, humanities, and social science scholars, this means OA publishing is experienced less as a political or ethical choice and more as an administrative obligation, tightly entangled with prestige metrics such as citation counts and journal rankings.[7]

As Janneke Adema and Samuel Moore note, publishing labour is increasingly caught between "unmeasurable service work and metricised performance targets … affective, open-ended, collegiate labour, while also being quantified and monitored as anxiety-inducing performance management."[8] Under pressure to produce work that is legible to evaluative systems – publishable, citable, and easily measured – arts, humanities, and social science scholars around the globe increasingly adjust their scholarly practices to fit dominant publishing norms and the English-language, high-ranking, journal-centred outputs privileged by evaluation systems as the most visible, citable, and professionally rewarded.[9] This evolution narrows methodological, epistemic, and procedural possibilities: scholars favour more linear and generalisable modes of argumentation;[10] scale back speculative, emergent, or relational forms of inquiry;[11] strategically shift to writing in English;[12] and redirect the social and collaborative practices that underpin research into activities aimed at visibility, networking, or strategic career advancement.[13] These dynamics reinforce prestige economies that devalue subjective, embodied, community-rooted, and non-Western forms of knowledge, while also producing dissonance between scholars' intellectual and ethical commitments and the narrow forms of value recognised by institutions.[14] The resulting stress and alienation are unevenly distributed, putting more pressure on early-career researchers, women, scholars of colour, queer scholars, and neurodiverse or disabled researchers.[15]

While there has been growing attention to how these pressures shape the relational and emotional experience of academic life, in infrastructure work the social and affective dimension has remained under-acknowledged. Conversations about publishing infrastructures still tend to prioritise technical, administrative, or policy-driven concerns, leaving the emotional, relational, and care-based aspects of infrastructuring largely invisible. This has also been true for much of the Copim community’s work – designing new organisational models, outlining governance structures, and developing and documenting software.

As Susan Leigh Star famously observed, infrastructure is often invisibilised: "People commonly envision infrastructure as a system of substrates – railroad lines, pipes and plumbing, electrical power plants, and wires. It is by definition invisible, part of the background for other kinds of work. It is ready-to-hand."[16] This remains true in scholarly publishing, where infrastructure tends to recede into the background and becomes visible primarily through breakdown. Even when addressed directly, it is frequently represented through technical diagrams or system maps that foreground components and processes rather than the human relationships, social practices, and emotional engagements through which infrastructures actually function, endure, or falter.

Against this background, ServPub’s emphasis on social and affective dimensions offered a vital complement to this largely technical imaginary of infrastructure in scholarly publishing practice and research – and productively widened the Copim community’s own infrastructural horizon towards a more holistic understanding of how publishing systems are configured and sustained in practice.

This is consonant with more recent ethnographic and critical work that reorients attention toward the practice of infrastructuring and the relational labour it entails. Calkins and Rottenburg describe infrastructures as "experimental material-semiotic practices interweaving social, economic, political, and legal orderings with moral reasoning and technical networks that inevitably produce new and unpredictable assemblages that reconfigure the world."[17] This framing foregrounds infrastructure as situated, contingent, and affectively charged – shaped less by its technical components than by the social relations that hold it together.

Joe Deville has extended this perspective by analysing how affect is entangled in the infrastructuring of scholarly publishing and arguing that OA publishing infrastructures are situated and affectively mediating interventions, and that attending to affects such as hope, disappointment, and optimism is vital for materialising more equitable publishing futures.[18] Julien McHardy similarly notes that "love is our business model"[19]: an insistence that attachment, ethical commitment, relational accountability, and collegial solidarity are not antithetical to publishing but central to sustaining non-extractive, community-led infrastructures that resist the ‘cold’ bureaucratic logics governing much of the contemporary publishing landscape.

This orientation towards the social and affective dimensions of infrastructuring also sits in close conversation with wider interventions in the field of OA publishing, to which the Experimental Publishing Group is intellectually, politically, and practically indebted: Across the histories of OA publishing, advocates have challenged prevalent – for example, funder- and policy-mandated – approaches that equate openness with the mere removal of technological, economic, or legal barriers to research outputs. Drawing on relational worldviews such as buen vivir in Latin America, Ubuntu in Africa, and the work of theorists such as Arjun Appadurai and Boaventura de Sousa Santos, some scholars argue that OA publishing must instead be understood as a plural, contested practice grounded in epistemic justice: questioning whose knowledge counts and who is authorised to speak.[20] Others, on the basis of Chantal Mouffe’s agonistic pluralism and Étienne Balibar’s conception of democratisation as an ongoing and conflictual process, conceptualise OA as something sustained through disagreement, experimentation, and reflexivity rather than achieved through the removal of technical access barriers alone.[21] Still others locate the transformative potential of OA publishing in activist publishing traditions rooted in anti-capitalist, feminist, queer, anti-colonial, anti-racist, and labour movements. These include the Combahee River Collective, Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, Precarias a la Deriva, and Cita Press – initiatives that practise collaborative publishing as a form of resistance to dominant white, Western, patriarchal, and capitalist epistemologies.[22]

Building on these interventions, OA publishing has been framed as a doing, "less a project and model to be implemented, and more a process of continuous struggle and critical resistance"[23]; "an entry point to intervene into the hegemonic system of traditional scientific knowledge"[24]; "a way to dis-establish the practice of admitting only those who speak our language or who position themselves as we do"[25]; or an "undoing of scholarship," a sustained effort to deconstruct the everyday operations of classed, gendered, and racialised power within academic processes.[26] Other formulations emphasise OA publishing as a refusal of the "spirit of competition and individualism" and the cultivation of "friendship and cooperation" in editorial and publishing practices.[27] Still others position OA as an opportunity to rethink research cultures themselves by enabling bottom-up critical discourses and collaborative infrastructures in response to the top-down corporatisation of university life.[28]

Taken together, these strands of work – of which ServPub offers a situated, infrastructural expression – reorient OA publishing towards the social, epistemic, and affective conditions through which knowledge is created, validated, and shared. In doing so, they reshape the very notion of openness on which it relies. As Adema argues, doing OA involves cultivating "forms of openness that do not simply repeat established forms… or succumb to the closures"[29] produced by the institutionalisation of OA – such as its codification into policy mandates and compliance checklists, as discussed earlier. In this way OA publishing opens space "for reimagining what counts as scholarship and research… what an author, a text, and a work actually is."[30] Similarly, Denisse Albornoz, Angela Okune, and Leslie Chan call for an understanding of openness grounded in political engagement, community participation, and the collective imagination of "futures radically different from the present".[31]

The ServPub project contributes to these reorientations of OA publishing by demonstrating how they can be enacted within the practical work of infrastructuring. The team’s emphasis on non-extractive collaboration resonates strongly with the traditions outlined above which understand OA publishing not as the removal of access barriers alone, but as a situated, justice-oriented, and epistemically accountable practice. In conversations for our documentation of the project, a member of In-grid referred to the project as "a social project" and said that "acknowledging the social aspects of it is as important as it being a technical experiment." The infrastructuring has been first and foremost a collective practice of bringing together a web of interdependencies, alliances, and the values of resisting corporate hegemony in publishing. In this context, in our conversations with the team, non-extraction emerged as a practised form of infrastructuring, sustained through reciprocity, shared responsibility, and mutual care across differently positioned contributors. As Systerserver put it, "we are always working with limited resources, so the question becomes how we can share those to compensate each other with time, knowledge, and effort." Such work requires acknowledging how collaborators are situated within extractive systems, and how these systems distribute privilege and precarity unevenly. Many participants – including those employed in UK higher education – operate under shared conditions of precarity, making it crucial to attend to how power, recognition, and vulnerability circulate and shift across institutional and non-institutional settings. As In-grid noted, "in the context of 'ServPub' it has been important to acknowledge the differences in privilege between groups... alongside moving funding around and trying to repurpose it toward those without access." Participants also stressed the importance of attending to non-material and relational forms of labour. As noNames observed, this includes recognising and crediting work already undertaken by others – particularly in contexts where academic actors have historically drawn on community knowledge without acknowledgement. ServPub has made these contributions visible through, for instance, its "Infrastructure Colophon", which documents community labour, tools, and situated expertise as part of the infrastructure itself.[32]

Through this focus, ServPub foregrounds the social and affective labour through which publishing infrastructures actually function, and insists that these dimensions must be treated as consequential rather than peripheral. Doing so requires redistributing decision-making power, recognition, and resources in ways that make relational, collaborative, and reciprocal forms of work structurally significant rather than merely supplementary. This, in turn, demands rethinking what publishing infrastructures are for and how they are organised: redesigning workflows – from peer review and editorial labour to technical maintenance, documentation, and credit attribution – so that they sustain relations of mutual support, epistemic accountability, and non-extraction. In this sense, ServPub shows that OA publishing is not merely about making content available, but about cultivating forms of openness that centre the social, epistemic, and infrastructural conditions through which knowledge is produced, validated, and shared, and that transform how power circulates across these sites. This book offers a practical and situated insight into how such commitments can be enacted in day-to-day infrastructuring work.

Content Index

Being Book

What does it mean to publish? Put simply, publishing means making something public (from the Latin publicare, ‘make public’) but there’s a lot more at stake, not simply concerning what we publish and for whom, but how we publish. It is inherently a social and political process, and builds on wider infrastructures that involve various communities and publics, and as such requires reflexive thinking about the socio-technical systems we use to facilitate production and distribution, including the choice of specific tools and platforms. In other words, publishing entails understanding the wider infrastructures that shape it as a practice and cultural form.

This book is an intervention into these concerns, emerging out of a particular history and experimental practice often associated with collective struggle.[33] It is shaped by the collaborative efforts of various collectives involved in experimental publishing, operating both within and beyond academic contexts (and hopefully serving to undermine the distinction between them), all invested in the process of how to publish outside of the mainstream commercial and institutional norms.[34] So-called "predatory publishing" has become the default business model for much academic publishing, designed to lure prospective and career-minded researchers into a restrictive model, that profits from the payment of fees for low quality services.[35] For the most part, academics are unthinkingly complicit, compelled by a research culture that values metrics and demands productivity above all else, and tend not to consider the means of publishing as intimately connected to the argument of their papers. As a result there's often a disjunction between form and content.

Public-ation

Despite its apparent recuperation by the mainstream, the ethics of Free/Libre and Open Source Software (FLOSS) provides the foundation for our approach, as it places emphasis on the freedom to study, modify and share information.[36] These remain core values for any publishing project that wants to maximise its reach and use, as well as enable re-use within a broader and expandable community.[37] What FLOSS and experimental publishing have in common is the need to address the intersection of technology and sociality, and support communities to constitute themselves as publics not simply in terms of the ability to speak and act in public, but through being able to construct their own platforms, what Christopher M. Kelty has referred to as a "recursive public."[38]

For the most part, distribution of academic publications is still largely organised behind pay-walls and through reputation or prestige economies, dominated by major commercial publishers in the Global North.[39] When open access is adopted, for the most part it remains controlled by a select few companies that operate oligopolistic structures to protect their profit margins and positions in the marketplace.[40] As such it is not surprising to realise that the widespread adoption of open access principles in academic publishing, once intended to democratize knowledge, have become a new profit engine for publishers. In these hands, open access provides as a smokescreen for business as usual, much like greenwashing for the environment.

This book is an attempt to offer a different production and distribution approach to publishing, and one that is less extractive in terms of its use of resources. Our approach is grounded in collective working practices and shared values that push back against dominant big tech/corporations and the drive toward seamless interfaces and scale-up efficiency. To repeat, our concern lies in the disjunction between the critical rigour of academic texts and the use of conventional modes through which they are produced that lack criticality. By criticality, we mean to go beyond a criticism of conventional publishing and to further acknowledge the ways in which we are implicated at all levels in the choices we make when we engage with publishing practices. This includes not only the tools we use -- to design, write, review and edit -- but also the broader infrastructures such as the platforms and servers, within, and through which, they operate. It is this kind of reflexivity that has guided our approach throughout the project: moving beyond the notion of the book as a discrete object and instead conceiving of it as a relational assemblage in which its constituent parts mutually depend on and transform one another in practice.

We have adopted the phrase "publishing as collective infrastructure" as our title because we want to stress these wider relational properties and how power is distributed, as part of the hidden substrate that includes tools and devices but also logistical operations, shared standards and laws, as Keller Easterling has put it. Infrastructure allows information to invade public space, she argues -- interestingly, just as architecture was killed by the book with the introduction of the Gutenberg printing press.[41] This is why we consider it important to not only expose its workings but also acquire the necessary skills -- both technical and conceptual -- to be able to make infrastructures otherwise.

The argument of Easterling, and others, recognises that infrastructure has become a medium of information and mode of governance, exercised through actions that determine how objects and content are organised and circulated. Susan Leigh Star is another who has also emphasised that "infrastructure is a fundamentally relational concept," operationalised through practices and wider ecologies.[42] Put simply, infrastructures involve "boring things,"[43] and the trick of the tech industry is to make these operations barely noticeable, so in this sense they are ideological as the underlying structures seem natural. Tools like word processors, for example, do not just allow us to produce content but also organise it particular forms and styles, auto-correcting our expression through the epistemic norms encoded in the software. The infrastructures of publishing are powerful in this way as they distribute information on the page through words, and at the same time through the wider operating systems that shape how we write and read. If we are to reinvent academic publishing, this must occur at every layer and scale -- what we might call a 'full-stack' transformation -- which includes the social and cultural aspects that technology influences and is influenced by. Here we make reference to 'full stack feminism' which calls for a rethinking of how digital systems are developed, applying the principles of intersectional feminism -- itself an infrastructural critique of method -- to critically engage with all layers of implementation.[44]

Background-foreground

In summary, the book you are reading is a book about publishing a book, a tool for thinking and making one differently, drawing attention to these wider structures and recursions. It sets out to acknowledge and register its own process of coming into being -- as an onto-epistemological object so-to-speak -- and to highlight the interconnectedness of its contents and the multiple processes and forms through which it takes shape in becoming book.

Given these concerns, we continue to find it perverse that academic books are still predominantly written by individual authors and distributed by publishers as fixed objects in time and space. It would surely be more in keeping with the affordances of the technology to stress collaborative authorship, community peer review and annotation, as well as other messy realities of production. This would allow for the development of versions over time, as Janneke Adema has argued, "an opportunity to reflect critically on the way the research and publishing workflow is currently (teleologically and hierarchically) set up, and how it has been fully integrated within certain institutional and commercial settings."[45] An iterative approach would suggest other possibilities that draw publishing and research processes closer together, and within which the divisions of labour between writers, editors, designers, software developers could become entangled in non-linear workflows and interactions. Through the sharing of resources and their open modification, generative possibilities emerge that break out of protectionist conventions perpetuated by tired academic procedures (and tired academics) that assume knowledge to be produced in standardised ways, and imparted through the reductive logic of input/output.

Our approach is clearly not new. It draws on multiple influences, from the radical publishing tradition of small independent presses and artist books as well as other experimental attempts to make interventions into research cultures and pedagogy. We might immodestly point to some of our own previous work in this connection, including Aesthetic Programming, a book about software, imagined as if software.[46] It draws upon the practice of forking in which programmers are able to make changes and submit merge requests to incorporate updates to software using version control repositories (such as GitLab). The book explores how the concept of forking can inspire new practices of writing by offering all contents as an open resource, with an invitation for other researchers to fork a copy and customise their own versions of the book, with new references and reflections, even additional chapters, all aspects open for modification and re-use.[47] By encouraging new versions to be produced by others in this way, we aim to challenge publishing conventions and exploit the technical affordances of the technologies we use that encourage collectivity. Clearly wider infrastructures are especially important to understand how alternatives emerge from the need to configure and maintain more sustainable and equitable networks for publishing, and that remain sensitive to all that contribute to the shared effort (concerning readers, writers and programmers alike). All this goes against academic conventions that require books to be fixed in time and follow narrow conventions of attribution and copyright.[48]

The collaborative workshops co-organised by the Digital Aesthetics Research Center at Aarhus University and transmediale festival for art and digital culture based in Berlin provide a further example of this in practice. Since 2012, these workshops have attempted to make interventions into how academic research is conducted and disseminated.[49] Those taking part are encouraged to not only engage with their research questions and offer critical feedback to each other through an embodied peer review process, but also to engage with the conditions for producing and disseminating their research as a shared intellectual resource.

The Minor Tech workshop from 2023 made these concerns explicit, setting out to address alternatives to big (or major) tech by drawing attention to the institutional hosting, both at the in-person event and online.[50] In this way, the publishing platform developed for the workshop can be understood to have a pedagogic function in itself, allowing for thinking and learning to take place as part of the wider socio-technical infrastructure. Building on this, the subsequent workshop Content/Form further developed this approach, working in collaboration with Systerserver and In-grid. Using the ServPub project as a technical infrastructure on which to ground the pedagogy, we were able to exempify how the tools and practices used for our writing shape it, whether acknowledged or not.[51] The process of setting up the server is described in subsequent chapters, but for now it is important to register how its presence in the same space as the workshop helped to place emphasis on the material conditions for collective working and autonomous publishing -- for publishing as collective infrastructure.

Self-hosted servers

The server needs be set up but also requires care, rather differently to the ways care has become weaponised in mainstream institutions. As Nishant Shah describes, care has become something that institutions purport to do, with endless policies and promises for well-being and support, but without threatening the structures of power that produce the need in the first place.[52]In our case, we would argue for something more along the lines of "pirate care," in which the coming together of care and technology can question "the ideology of private property, work and metrics."[53] Care in this sense comes closer to the work of feminist scholars such as Maria Puig de La Bellacasa who draws attention to relations that "maintain and repair a world so that humans and non-humans can live in it as well as possible in a complex life-sustaining web."[54]

Feminist servers follow these principles, wherein practices of care and maintenance are understood as acts of collective responsibility. It is with this in mind that we have tried to engage more fully with affective infrastructures that are underpinned by intersectional and feminist methodologies. Systerserver, for instance, operate as a feminist, queer, and anti-patriarchal network, which prioritises care and maintenance, offers services and hosting to its community, and acts as a space to learn system administration skills and inspire others to do the same[55]. Our further inspiration is "A Transversal Network of Feminist Servers" (ATNOFS), a project formed around intersectional, feminist, ecological servers whose communities exchanged ideas and practices through a series of meetings in 2022.[56] The publication that emerged from these meetings was released in a manner that reflects the collective ethos of the project. A limited number of copies were printed and distributed through the networks of participants and designed to be easily printed and assembled at home, thus reinforcing commitment to collaboration and access. More on this project is included in the following chapter. For now, it is worth adding that the project responded to the need for federated support for self-hosted and self-organised computational infrastructures across Europe although the UK was notably absent. Indeed part of our motivation for ServPub is to address the perceived need to develop a parallel community of shared interest around experimental publishing and affective infrastructures in London.[57]

We hope it is clear by now that our intention for this publication is not to valorize feminist servers or free and open-source culture as such but to stress how technological and social forms come together to expose power relations. This comes close to the position that Stevphen Shukaitis and Joanna Figiel have elaborated in "Publishing to Find Comrades," a phrase which they borrow from the Surrealist André Breton. Their emphasis is not to publish pre-existing knowledge and communicate this to a fixed reader but to work towards developing the appropriate social conditions for the co-production of meaning and action.

[58]The openness of open publishing is thus not to be found with the properties of digital tools and methods, whether new or otherwise, but in how those tools are taken up and utilized within various social milieus. [...]

Thus, publishing is not something that occurs at the end of a process of thought, a bringing forth of artistic and intellectual labor, but rather establishes a social process where this may further develop and unfold.

In this sense, the organization of the productive process of publishing could itself be thought to be as important as what is produced.

We agree. The process of making a book is not merely a way to communicate the contents but to invent organisational forms with wider social and political purpose. Can something similar be said of the ServPub project and our book? That's our hope. Attention to infrastructure is significant here, as well as the affordances of the tools we use, in allowing for reflection on divisions of labour, the conditions of production, the dependencies of support networks, and sustainability of our practice as academics and/or cultural workers. Moreover, the political impulse for our work draws upon the view that the tools of oppression offer limited scope to examine that oppression and their rejection is necessary for genuine change in publishing practices. Here we paraphrase Audre Lorde of course.[59]

As for the specific tools for this book, we have used Etherpad for drafting our texts, a free and open source writing software which allows us to collaborate and write together asynchronously. As an alternative to established proprietary writing platforms that harvest data, a pad allows for a different paradigm for the organisation and development of projects and other related research tasks. To explore the public nature of writing, Etherpad makes the writing process visible, as anyone of us can see how the text evolves through additions, deletions, modifications, and reordering. One of its features is the timeline function (called Timeslider in the top menu bar), which allows users to track version history and re-enact the process performatively. This transparency over the sociality and temporality of form not only shapes interaction among writers but also potentially engages unknown readers in accessing the process, before and after the book itself.[60] Another feature of a pad is that authors are identifiable through colours, usernames are optional and writing is anonymous by default. Martino Morandi has described this as "organizational writing," quoting Michel Callon’s description of "writing devices that put organization-in-action into words," and how writing in this way collectively "involves conflict and leads to intense negotiation; and such collective work is never concluded".[61]

Logistical operations

Apart from writing the book, and drawing attention to its organisational form, it is important to register that we are collectively involved in all aspects of its making. The production process -- including writing and peer review, copyediting and design -- is reflected in the choice of other tools and platforms that we are using as well as the constitution of the collectives involved. Using MediaWiki software and web-to-print layout techniques, ServPub is an attempt to circumvent standard academic workflows and instead conflate traditional roles of writers, editors, reviewers, designers, developers, publishers alongside the affordances of the technologies. To put it plainly, this means rejecting proprietary software such as Abode Creative Cloud and designing by other means, as indicated by the ironic naming of Creative Crowds (CC) as part of our working group.[62] Indeed, the distributed nature of our endeavour is reflected in the combinations of those involved, directly and indirectly, across the different entities (or what we called chosen dependencies) involved who provide the necessary skills and support for the project's realisation. This includes building on the work of others involved in the development of the tools such as the various iterations of 'wiki-to-print' and 'wiki2print', not least involving CC, which In-grid have further adapted as 'wiki4print' for this book.[63] The book object is just one output of a complex set of interactions and exchanges of knowledge across time and space.

As mentioned, the divisions of labour are somewhat collapsed, and the activities that make up the publishing pipeline are reinvented in relation to the various tools and the platforms they support. This is inevitably not without its challenges, especially when such a diverse group of people are involved, each with their own experiences, positionalities, life and employment situations. One of the many challenges of a project like this has been to account for these differences, which include the complexities of unpaid and paid labour. We have tried to address or acknowledge potential 'discomfort' associated with the project throughout our work together in our meetings.[64] Perhaps this is particularly important when engaging grassroots collectives who often remain suspicious of academia as a zone of privilege without recognising other factors such as cultural differences and rising precarity in the sector.

Discomfort is important to the praxis of ServPub, emerging as we navigated complex questions related to reputation hierarchies and accreditation, as well as the nature of the institutional infrastructures that support the work. Challenges include uneven access to resources, disparities in institutional support, and the ongoing negotiation of additional labour which reveals some of the power struggles individuals/collectives face within their own particular situations, even as they remain committed to the project. All embrace feminist methodologies, but this commitment is not without differences of interpretation. Language itself also acts as a destabilizing factor, as not all contributors are native English speakers, leading to subtle miscommunication and moments that demand continuous exercise of trust, open communication and negotiation of meaning. Consensus-building within this diverse project entails negotiating differing expectations and end-goals, from contributing to community and personal research interests to advancing academic careers. Issues are further complicated by the politics of documentation and attribution, as contributors strive to fairly represent both individual and collective labour while remaining vigilant against replicating extractive academic norms and hierarchies. Rather than glossing over the inevitable contradictions, we have tried to approach them openly, slowing down the collective decision-making processes, and leaving space for open dialogue, to foster solidarity that allows any tensions to become spaces for mutual learning and collective growth.

In the article by Shukaitis and Figiel, these tensions are characterised as a question of who has access to resources and the reliance on forms of free labour in cultural work,[65] although it should be noted that they are mindful not to reduce everything to the question of financial remuneration. Mirroring what commonly takes place in the arts, they refer to how unseen and unpaid labour is central to academic publishing, in particular we can refer to the peer review process, and how particular kinds of labour are valorised over others.[66] Careful consideration must be given to the divisions of labour in publishing, with sensitivity to how roles and subject positions are shaped by intersectional structures of race, gender, class, and other forms of oppression.

This attentiveness to the social and material relations of publishing — as a means of establishing new social relations and engaging critically with infrastructure — further resonates with what Fred Moten and Stefano Harney have described as the "logisticality of the undercommons".[67] In The Undercommons, they refer to how logistics — the invisible infrastructures that move people, goods, and information — are central to how institutions function under global capitalism. The undercommons refers to spaces or modes of being that exist outside of formal institutions like the university or the state. Although we cannot claim to be part of the undercommons, we learn from its ways of knowing, relating, and organising that don't reproduce existing power structures. This also resonates with David Graeber's rejection of academic elitism and instead embraces lived experience and collective imagination.[68] Like Jack Halberstam’s articulation of "low theory" in The Queer Art of Failure as a way to rethink failure and critique capitalism, as well as to engage theory from the margins, rather than from rigid and legitimated systems of knowledge often published in academic journals.[69] These ideas help us to reflect on how to share resources, how to circulate our ideas and how to choose our dependencies, without reproducing the structures of power-knowledge associated with academia publishing.

Minor publishing

As the publisher of Harney and Moten's work, and this book, Minor Compositions follows such an approach. Its naming resonates here too, alluding to Gilles Deleuze & Félix Guattari's book on Kafka, the subtitle of which is "Towards a Minor Literature."[70] As mentioned above, we previously used this reference for our 'minor tech' workshop and followed the three main characteristics identified in Deleuze and Guattari's essay, namely deterritorialization, political immediacy, and collective value.[71] As well as exploring our shared interests and understanding of minor tech in terms of subject matter, we sought to implement these operational principles in practice. This maps onto our book project well and its insistence on small scale production, as well as the use of the ServPub infrastructure to prepare the publication and to challenge some of the production models of journals and conference proceedings.

The publishing project of Minor Compositions is explained succinctly by Stevphen Shukaitis as deriving "not from a position of ‘producer consciousness’ ('we’re a publisher, we make books') but rather from a position of protagonist consciousness ('we make books because it is part of participating in social movement and struggle')".[72] Aside from the allusion to minor literature, the naming also makes explicit connection to the post-Marxism of autonomist thinking and practice, building on the notion of collective intelligence, or what Marx referred to, in "Fragment on Machines", as general (or mass) intellect.[73] The idea of general intellect remains a useful concept for us as it describes the coming together of technological expertise and social intellect, or general social knowledge, and recognition that although the introduction of machines under capitalism broadly oppresses workers, they also offer potential liberation from these conditions. The same in the case with infrastructure as we have tried to argue.

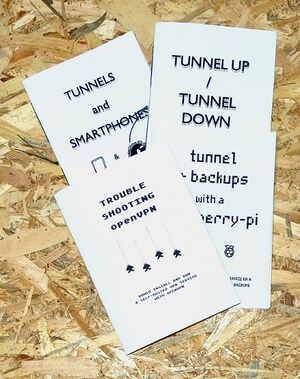

In the case of publishing, our aim has been to extend its potential beyond its functionary role to make books as fixed objects and generate surplus value for publishers, and instead engage with how learning and thinking with others might establish other social relations. In our interview sessions with the organisers of Open Book Futures (our sponsors), we have identified that working together is a way to learn together, a way to share skills and knowledge, often taken from experience of computational practice and then applied to publishing, trying to think outside of the established conventions of both. This is the case even when the practices of publishing is relatively unknown, as identified by In-grid. Systerserver, on the other hand, build on their experience making zines for technical documentation The combination of our experiences here leads us to speculate on new forms and brings us back to the term 'composition' (or recomposition) inasmuch as it emphasises that power in the form of infrastructure does not transform itself as the result of evolution but from struggles that arise from how labour is technically arranged. Our point is that what we refer to as academic publishing comes with its own set of conventions that tend to go against the grain of radical self-organisation.

Radical referencing is a good example of this, as a way to address the canon and offering other positions and voices that tend to be left out of the discussion. The book has tried to take this approach seriously, diverting from the reliance on big name academics in recognition that ideas evolve far more organically through conversations and encounters in everyday situations. The last chapter explores this in more detail and it becomes clear that hierarchies of knowledge are reinforced through referencing and the cultural capital attached to certain theorists and theory that comes and goes with academic fashions. In the last chapter, Celia Lury's notion of ‘epistemic infrastructure’ points to how organisational structures shape the processes by which knowledge becomes knowledge.[74] Here we are also introduced to Sara Ahmed’s uncompromising intervention in the politics of referencing in which they choose to exclude white men from citation to somewhat balance the books.[75] If we are to take an intersectional approach here, then clearly there are multiple exclusions which need to be engaged, and tactics to address the infrastructures that question the privileging of some names over others.[76]

To continue with a brief overview of the structure of the book, we combine practical description with a discussion of the implications of our approach. In the “Preface”, the overall context for the project is explained in more detail, how the book arises from shared commitments to open access book publishing. Not least this is useful to situate our work within a larger set of interests that devalue subjective, embodied, community-rooted, or non-Western epistemic traditions. In what follows, “Being Book”, we outline some of our motivations and our attention to the concept of infrastructure as a means to expose some of the inherent power relations in book production. As you are reading this part way through, we hope it’s clear by now that the idea is to reject the conservative impulses of academic publishing and instead work towards what we are calling autonomous publishing. How we do this, and what is at stake, is further unfolded across the various chapters that follow.

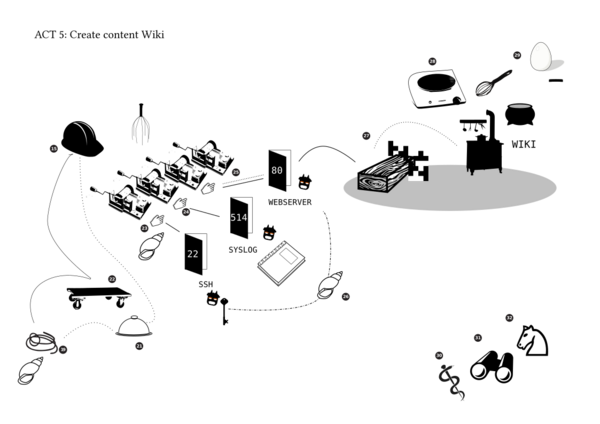

“Ambulant Infrastructure” describes how the portability of the server helps to identify boundaries of the various processes involved in maintaining the technologies that support the project, to reveal the materiality and spatial politics. In “Feminist Networking,” we get further detail on the technical setup of the network infrastructure but more importantly how this requires a shared commitment to reject our dependencies on cis-male dominated extractivist technologies. We get more detail on some of the design decisions in making the book in the following chapter, “FLOSS Design: Frictitious Ecologies,” structured around an interview between In-grid and Creative Crowds. The affordances of the technical tools like wikis emphasise the coming together of technical and social aspects, of writing and designing together. Similarly, more of the sharing of process is discussed in “Praxis Doubling,” where technical documentation combines with subjective reflection. With updatable docs online, we hope others will be able to replicate and extend the work through the release of all software on a shared git repository/wiki platform.

Further reflection on the broader infrastructures for publishing is included in a short chapter “Angels of Our Better Infrastructure.” Here it becomes evident that we consider our work to be unfinished, formed by the efforts of publics and publishing practices that are always precarious, partial, and provisional. It is also evident that we build on the work of others who have inspired our work to date, through a “Collective Statement” which demonstrates the provenance of our thinking. Helpful here too is the chapter “Referencing,” already mentioned, which supplements the convention of a list of references with reflection on how their formation is an important part of what counts for knowledge or not, challenging the status of sources and their symbolic value. This helps to stress the social, epistemic, and affective conditions through which knowledge is created, validated, and shared. Our work is collectively formed, a consequence of multiple meetings and conversations formed out of the messy combinations of individuals and collectives. The publication is part of the process of opening up the conversation to others.

Autonomous publishing

The different groups have tried to identify some of the challenges and opportunities in making a book like this. In our interview sessions they state that working together is a way to express autonomy and choose our dependencies.[77] This relates to the wider issue of consent according to one of the members of In-grid, and a baseline solidarity about what everyone is working towards and has agreed to, as part of a wider ethics of software development and community support. "We're choosing to be reliant on software's open source practices, drawing upon the work of other communities, and in this sense are not autonomous." As such, it seems important to clarify what we mean by autonomy or autonomous publishing, grounded in solidarity. There’s a complex discussion here that we simply don’t have space to rehearse in this book but broadly connects to the idea of artistic autonomy and practices to undermine the kinds of autonomy attached to the formalist discourse of art history.[78] One way to understand this better would turn to the etymology of the term which reveals ‘autos’ as self and ‘nomos’ as law, together suggesting the ability to write your own laws or self-govern. But clearly individuals are not able to do this in isolation from social context, and any laws operate in social context too and as part of broader infrastructures. It is no wonder much contemporary cultural practices are performed by self-organised collectives that both critique and follow institutional structures, managerial and logistical forms. No different is our own nested formation of a collective of collectives.

Making reference to collective struggle and autonomia allows us to draw attention to our understanding of the value of labour in our project as well as subjectivity of the worker.[79] Whereas Capital tries to re-establish the wage-work relation at all costs (even when speaking of house work as unpaid), an autonomist approach politicises work and attempts to undermine spurious hierarchies related to qualifications and different wage levels from full-time employment to casualisation in ways that resonate with our team. This has relevance, especially in the collective formation of collectives where some are waged and others not, some positioned as early career researchers and others with established positions. Who and how we get paid or gift our time, and what motivates this effort is variable and contested. As we have suggested earlier, that's important but not really the point.

All the same, an anarchist position is an attempt to dismantle some of the centralised (State-like) structures and replace them with more distributed forms that are self-organised. But this is not to say that power goes away of course. In our various collectives this power relation leads to inevitable feeling of discomfort as our precarities are expressed differently according to the situations in which we find ourselves. Yet when we recognise the system is broken, subject to market forces and extractive logic, Systerserver remind us that repair is possible, along with a sense of justice, other possibilities that are more nurturing of change. We'd like to think that our book is motivated in this way, not to just publish our work to gratify ourselves or develop academic careers or generate surplus value for publishers or Universities, but to exert more autonomy over the publishing process and engage more fully with publishing infrastructures and recognise that they operate under specific conditions that are not immovable. Our aim is to rethink publishing infrastructure and knowledge organization, to contest normalised forms and the politics they support, and to encourage others to do the same.

The publication that has emerged from this process reflects ongoing conversations and collective writing sessions between the various communities that have supported the development of our ideas in such a way that we no longer know who thought or write what. No matter. The book is a by-product of these entanglements and lived relations, open to ongoing transformation and the creation of differences, and operating across ever-shifting modes of knowing and becoming.

Ambulant Infrastructure

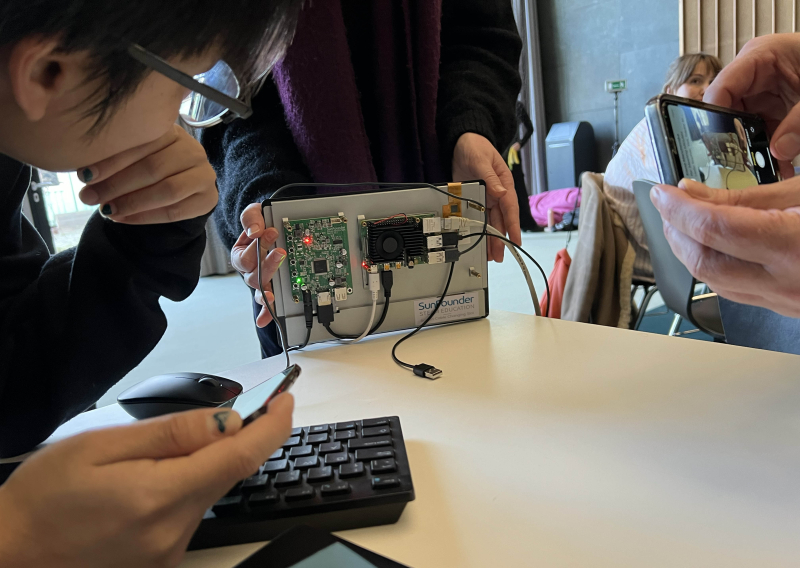

Wiki4print, the collective writing software for this book, is installed on the raspberry pi that hosts https://wiki4print.servpub.net/ and travels with us (see Figure 2.1). We have physically constructed our network of servers so that we can keep it's hardware by our side(s) as we use it, teach and experiment with it, and activate it with others. This chapter will consider the materiality of our particular network of nodes, our reasoning for arranging our infrastructure in the way we have and what it means to move through the world with these objects. By considering our movement from one place to another we can begin to understand how an ambulant server allows us to locate the boundaries of the software processes, the idiosyncrasies of hardware, the quirks of buildings and estates issues, and how we fit into larger networked infrastructures. We will consider how we manage departures, arrivals, and points of transience, reveal boundaries of access, permission, visibility, precarity and luck. This proximity to the server creates an affective relationship, or what Lauren Berlant called affective infrastructure, recognizing the need of the commons, building solidarity via social relations and learning together [80]. These precarious objects foster responsibility and care, allowing us to engage critically with the physicality of digital platforms and infrastructures that are entangled with emotional, social and material dimensions. In contrast to vast, impersonal cloud systems, our mobile server foregrounds flexibility, rhythm, and scale—offering a bodily, hands-on experience that challenges dominant industrial models that prioritize efficiency, automation, speed and large-scale resource consumption.

In this chapter we will examine our decision to arrange our physical infrastructure as mobile or ambulant and in view. To understand the material realities of cloud infrastructure, one would need to look not only at the computational hardware and software, but examine the physical architecture, cooling systems, power supply, national or spatial politics and labour required to run a server farm. In one of the talks that artist-researcher Cornelia Sollfrank gave on technofeminism, she referred to Brian Larkin's essay on "The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure[81]," where a basic definition of infrastructure is a “matter that enables the movement of other matter,” including, for example, electricity and water supply/tubes that enable the running of a server or a micro-computer. What then is the material body or shape of an ambulant infrastructure that moves between spaces? To reveal this materiality we will map our collective experiences in a series of stacks[82] of space. These spaces are reflective of our relative positions as artist*technologist*activist*academic:

- THE PUB / PUBLIC SPACES

- INSTITUTIONAL SPACES

- SUITCASES AS SPACE

- WORKSHOPS AS SPACE

- CULTURAL/SEMI-PUBLIC SPACES

- DOMESTIC/PRIVATE SPACES

- NATIONS / TRAVEL

By situating our mobile server within these diverse spatial contexts, we illuminate the complex interplay between technology, place, social and embodied experience, advancing a critical discussion of infrastructure that foregrounds the materiality of data, software, and social-technical processes alongside tangible infrastructure. This perspective brings us to an essential question: why does the mobility of servers matter?

Traveling server space: Why does it matter?

Many precedents have contributed to the exploration of feminist servers [83]. While there is significant focus on care, labor conditions, and maintenance, the technical infrastructure remains largely hidden from the general public as servers are fixed in location and often distant from the working group. We often perceive servers as remote, and large-scale entities, especially in the current technological landscape where terms like "server farms" dominate the discourse.

Rosa, a feminist server, as part of the ATNOFS project is considered as a travelling server which afforded collaborative documentation and notetaking at various physical sites where the meetings and workshops were taken place in 5 different locations throughout 2022. In addition Rosa is also part of self-hosted and self-organised infrastructures, engaging "with questions of autonomy, community and sovereignty in relation to network services, data storage and computational infrastructure" [84]. The naming was considered important in the context of a male-dominating discourse of technology: "We’ve been calling rosa ‘they’ to think in multiples instead of one determined thing / person. We want to rethink how we want to relate to rosa."[85] In this way the server itself performs an identity function that broadly reflects feminist values -- acting not as a neutral or passive machine, but as a situated, relational agent of care and resistance. It is a "situated technology" -- in the style of Donna Haraway’s concept "situated knowledge"[86] -- in that it emerges from particular bodies, contexts, and relations of power. The descriptors become significant:

Is it about self definition? – I am a feminist server. Or is it enough if they support feminist content? It is not only about identifying, but also whether their ways of doing or practice are feminist.[87]

To describe a server as feminist is not merely to identify who builds or uses it, but to consider how it is produced, maintained and engaged with -- in opposition to the patriarchal and extractive logic of mainstream computing. However, without careful qualification, the idea of a feminist server risks defaulting to white, ableist, and cis-normative assumptions, potentially obscuring interconnected systems of oppression. An intersectional approach is needed to account for the distributed forms of power in operation. In the publication, for instance, they argue that a focus on resources can connect issues related to "labour, time, energy, sustainability, intersectionality, decoloniality, feminism, embodied and situated knowledges. This means that, even in situations focusing on one specific struggle, we can’t forget the others, these struggles are all linked."[88]

The travelling rosa server is highly influential as it encourages ServPub members to rethink infrastructure—not as something remote and distant, but as something tangible, self-sustained and collective. It also highlights the possibility of operating and learning otherwise, without reliance on big tech corporations which is often opaque and inaccessible. While most feminist server and self-hosting initiatives have emerged outside of London[89], we are curious about how the concept of traveling physical servers could reshape a vastly different landscape—one defined by critical educational pedagogies, limited funding, and the pressures of a highly competitive art and cultural industry in the UK. The first consideration is skills transfer—fostering an environment where technical knowledge, caring atmosphere, and open-minded thinking are recognized and encouraged, enabling deeper exploration of infrastructure. This is also where the London-based collective In-grid, comes into the picture of ServPub.

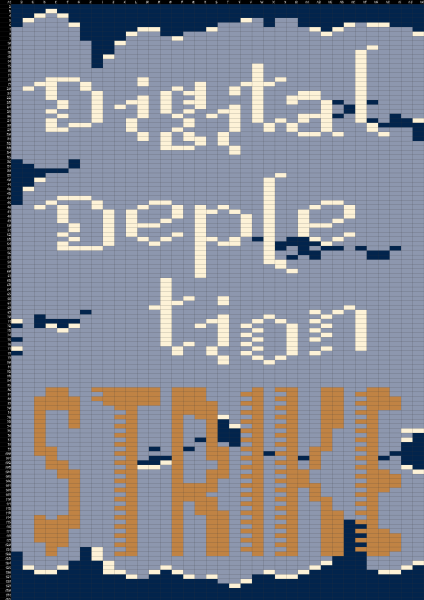

THE PUB / PUBLIC SPACES: Networking space

On the 8th of March 2023 (8M), an international strike called for a "hyperscaledown of extractive digital services" [90]. The strike was convened by numerous Europe-based collectives and projects, including In-grid, Systerserver, Hackers and Designers, Varia, The Institute for Technology in the Public Interest, NEoN, and many others. This day served as a moment to reflect on our dependency on Big Tech Cloud infrastructure—such as Amazon, Google, and Microsoft—while resisting dominant, normative computational paradigm through experimentation, imagination, and the implementation of self-hosted and collaborative server infrastructures.

Louise Amoore's Cloud Ethics[91] frames such actions as encounters with the "cloudy" opacity of algorithmic infrastructures, where responsibility cannot be pinned to transparent code or fixed moral rules but emerges in the partial, distributed relations across platforms, data centers, and human actors. The Strike's Webrings-hosted website-technicially a network of networks popular in the 1990s, which is decentralized, community-driven structures that cycle through multiple servers. 19 server nodes—including In-grid—participate, ensuring the content is dynamically served across different locations. When a user accesses the link, it automatically and gradually cycles through these nodes to display the same content. Webrings are typically created and maintained by individuals or small groups rather than corporations, forming a social-technical infrastructure that supports the Counter Cloud Action Day by decentralizing control, distributed relations and resisting extractive digital ecosystems.

On the evening of 8M, many of us—individuals and collectives based in London— gathered at a pub in Peckham, South London. The location was close to the University of the Arts London where some participants worked. What began as an online network of networks transformed into an onsite network of networks, as we engaged in discussions about our positionality and shared interest. This in-person meeting brought together In-grid, Systerserver and noNames collectives, shaping a collaborative alliance focused on local hosting, small scale infrastructure for research, community building, and collective learning.

INSTITUTIONAL SPACES

Within this context of decentralized and community-driven digital infrastructures, it is impossible to overlook the contrasting landscape of educational institutions. Many of us in the ServPub project are affilated with universities. In an academic context it is no easy matter to work in this way, as infrastructures are mostly locked down and outsourced to third parties, as well as often rely on big tech infrastructures.[92] For example, the widespread use of Microsoft 365 for organizing daily tasks, meetings, routines, and documents through SharePoint, a cloud-based collaboration and document management platform for team collaboration, document storage, and intranet services. Similarly, the institutional networked infrastructure Eduroam (short for 'Education Roaming') provides global access, secure connections, and convenience. However, it also comes with limitations and challenges, including IT control and network restrictions, such as port blocking to prevent unauthorized or high-bandwidth usage, as well as traffic monitoring under strict privacy policies. This protective environment inevitably trades off autonomy and user agency, making it difficult to engage with the infrastructure beyond mere convenience and efficiency.

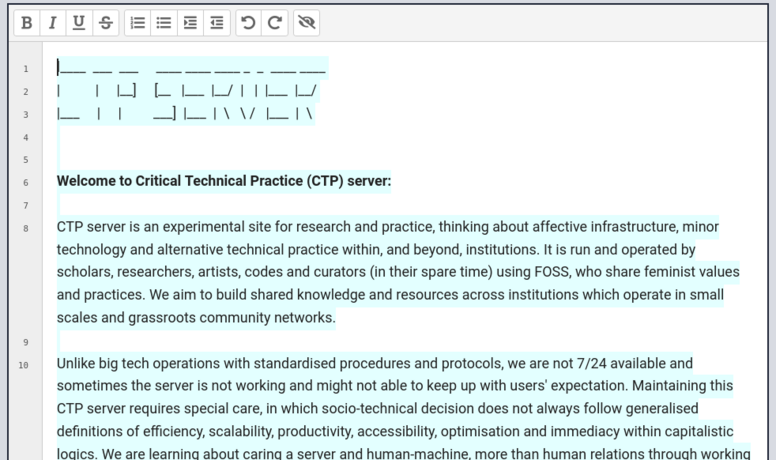

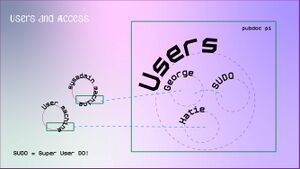

At Aarhus University, the CTP (critical-technical practice) server[93] (see Figure 2.4) is an ongoing attempt to build and maintain an alternative outside of institutional constraints.[94] This was a response to the problem of allowing access to outside collaboration and running software that was considered a security threat, and therefore needed careful negotiation with those responsible for IT procedures and policies.[95] In 2022, the CTP project invited a member of Systerserver to deliver a workshop titled "Hello Terminal," intended as a hands-on introduction to system administration. However, the remote access port was blocked, preventing anyone without a university account and Virtual Private Network (VPN) from logging in, significantly restricting participation and what people can do with the servers. If we want to understand infrastructure, fundamental questions such as what is a server and how to configure one naturally arise. Approaching these requires access to a computer terminal and specific user permissions for configuration or installation—areas traditionally managed by IT departments. Most universities, however, provide only "clean" server spaces (preconfigured server environments) or rely on big tech software and software that offer secure, easy-to-maintain solutions, limiting hands-on exposure to the underlying setup and infrastructure. This issue, among others, will be explored further in Chapter 3. When systems become standardized and enclosed, leaving little to no room for alternative approaches to learning. For researchers, teachers, students, and those who view infrastructure not merely as a tool for consumption and convenience but as an object of research and experimentation, opportunities to engage with it beyond predefined uses are limited. This lack of flexibility makes it difficult to explore and understand the black box of technology in ways that go beyond theoretical study. The question then becomes: how can we create 'legitimate' spaces for study, exploration and experimentation with local-host servers and small scale infrastructure within institutions?

Creating legitimate space to introduce other kinds of software in a university setting can be challenging. University IT departments may not always recognise that software fundamentally shapes how we see, think, and work, a point emphasized by Wendy Chun who argues that software is not neutral but deeply influences cognition, perception, and modes of working[96]. This aspect is a crucial part of teaching and learning that goes beyond simply adopting readily available tools. For example, our request to implement Etherpad, a free and open-source real-time collaborative writing tool widely used by grassroots communities for internal operations and workshop-based learning, illustrates this challenge. Unlike mainstream tools, Etherpad facilitates shared authorship and co-learning, aligning closely with our pedagogical values.

In advocating for its use, we found ourselves having to strongly defend both our choice of tools and the reasons why for example Microsoft Word was insufficient. IT initially questioned the need for Etherpad, comparing it to other collaborative platforms such as Padlet, Miro, and Figma. Their priority, we learned, was finding software that integrated easily with Microsoft — a choice driven by concerns around centralised management and administrative efficiency over pedagogical or experimental value. When we highlighted Etherpad’s open-source nature — and the opportunities it offers for adaptation, customisation, and community-driven development — we also pointed to how this reflects our teaching ethos: fostering critical engagement and giving students agency in shaping the tools they use. Despite this, we were still required to further justify our case by demonstrating how Etherpad supports teaching in ways that other mainstream software like Google Docs do not. It ultimately took nearly a year to establish this as a legitimate option. The broader point is that introducing non-mainstream, non-corporate software into institutional settings demands significant additional labour — not only in time, but also in the ongoing work of justification, negotiation, and communication.

The ServPub project began with the desire to make space for engaging software and infrastructure otherwise, emphasizing self-hosting and small-scale systems that enable greater autonomy for (un)learning. One of the goals is to explore what becomes possible when we move away from centralized platforms and servers, offering more direct ways to access the knowledge embedded in infrastructure and technology. Developing alternative approaches requires a deeper understanding of technology—beyond simply using them from well-defined, packaged and standardized solutions.

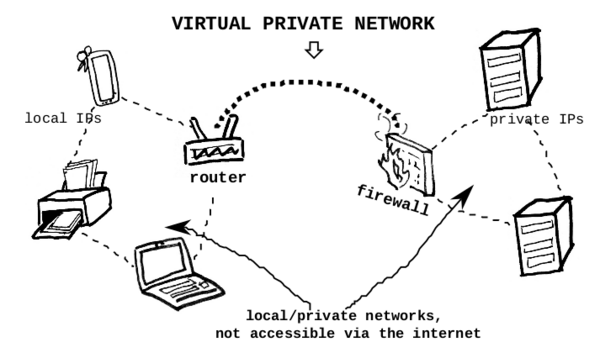

During our first ServPub workshop[97] at a university in London in 2023, where we configured the server using a Raspberry Pi, we encountered these constraints firsthand: the university’s Eduroam network blocked access to the Servpub VPN. Institutional network security policies often block VPN traffic and local network traffic as this traffic is considered insecure. VPNs can obscure user activity, bypass filtering systems, and introduce potential security risks. To maintain control, network administrators typically restrict the protocols and ports used by VPNs, resulting in such blocks within Eduroam environments. These restrictions create significant challenges for experimental and self-hosted projects like ours.

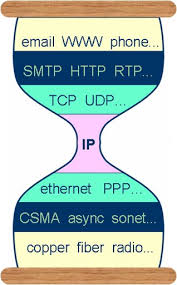

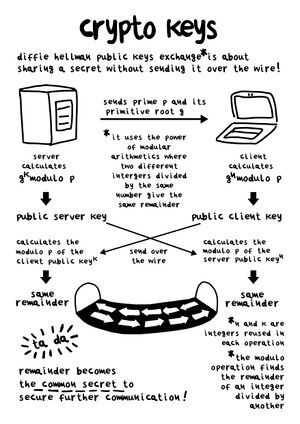

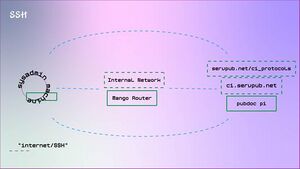

How then do we use protocols to communicate between devices in a shared network when this behaviour is considered risky? Using a router disconnected from the internet will allow local device-to-device communication within a classroom or workshop, however in order to be connected to the public internet a VPN and the use of mobile data is needed. VPNs are accessible online via a static IP address, requiring one server in a VPN to be stable. Within Servpub, one server is permanently running in Austria at mur.at which is responsible for routing all traffic from the public internet through our VPN network of ambulant servers. Two of our servers are ambulant Raspberry pi computers that serve up wiki4print.servpub.net and servpub.net, when those Raspberry Pis are offline these websites cease to be accessible. During some workshops run within educational institutions in order to facilitate local device-to-device communication and access to the Servpub VPN, we resorted to sharing one of the organizers’ personal hotspot connections (using a mobile data network), which itself is limited by a 15-user cap on hotspot sharing. While this is not an ideal solution, stepping outside of Eduroam is a necessary workaround to allow us to bring networked ambulant servers into workshop or teaching spaces.

Eduroam’s technical architecture and policies embed institutional control deeply into network access. While it is designed to provide secure and seamless global connectivity through standardized authentication protocols, it also enforces user dependency on institutional credentials and network policies that limit experimentation and autonomous infrastructure use. Our experience with Eduroam exemplifies these challenges, highlighting the broader tensions between institutional infrastructures and the desire for more self-determined, flexible technological practices.

This experience of navigating institutional constraints points to the significance of mobility and portability in our approach. Carrying our server with us enables a form of technological autonomy that challenges fixed infrastructures and their limitations. This brings us to consider the physical and conceptual implications of portability—what it means to live and work with servers inside suitcases, and how these objects become ambulant spaces in their own right.

SUITCASE AS SPACE

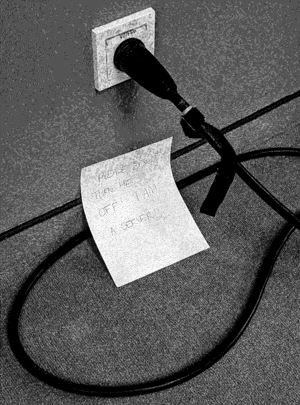

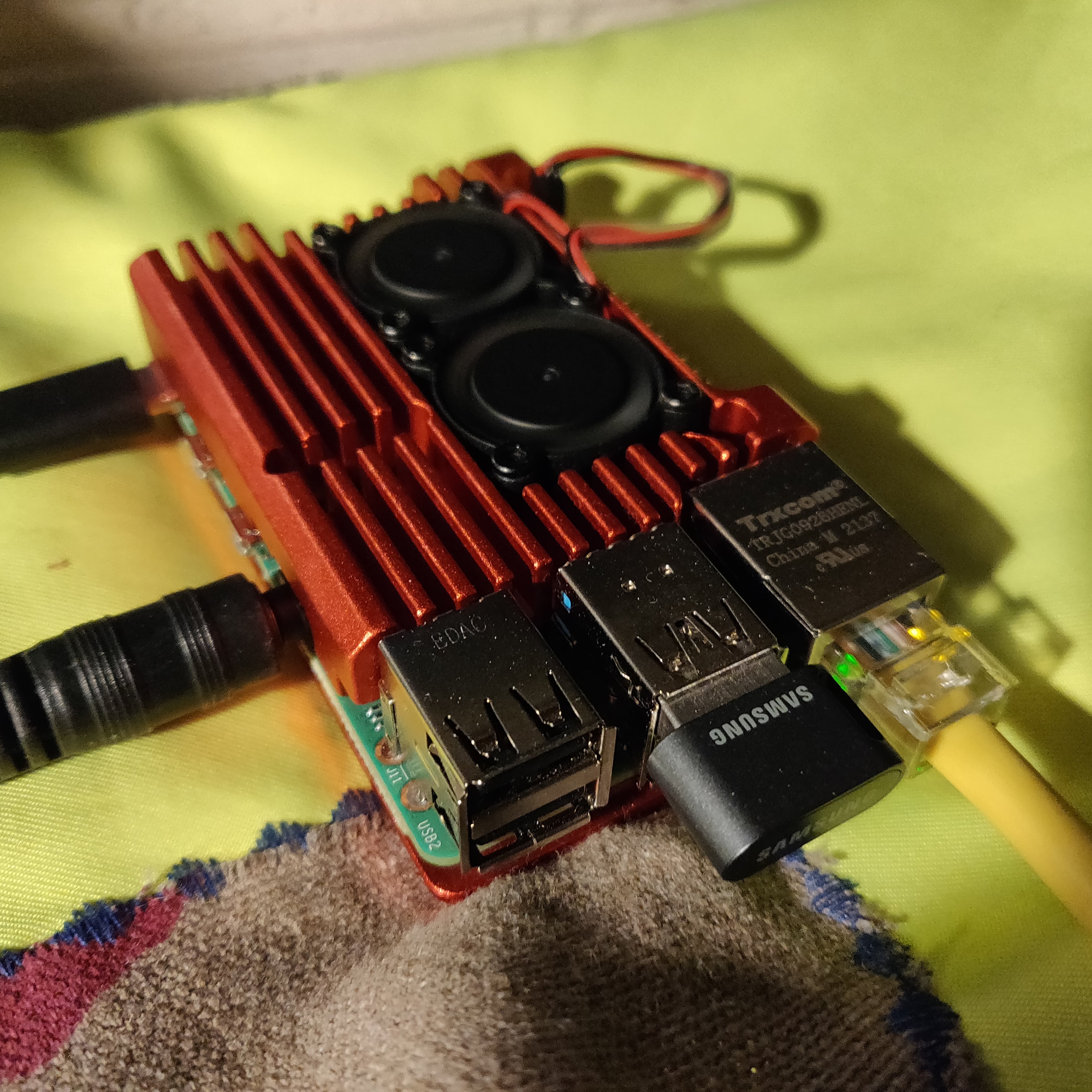

We have referenced the fact that our server can be brought with us to visit other places, the server runs on a computer. What that means in practice is a repeated unplugging and packing away of objects. We unplug the computer, literally and figuratively, from the network. In the case of wiki4print, the node unplugged, sans-electricity, sans-network is:

- Raspberry pi (the computer)

- SD memory card

- 4G dongle and sim card (pay-as-you-go)

- Touch Screen

- Mini cooling fan

- Heat-sink

- Useful bits and pieces (mouse, keyboard, power/ethernet/hdmi cables)

These items have been variously bought, begged and borrowed from retailers, friends and employers. We have avoided buying new items where possible, opting to reuse or recycle hardware where possible. We try to use recycled/borrowed items for two primary reasons. First, we are conscious of the environmental impact of buying new equipment, and are keen to limit the extent to which we contribute to emissions from the manufacturing, transportation and disposal of tech hardware. Secondly, we are a group working with small budgets, often coming from limited pots of funding within our respective institutions. These amounts of funding are most often connected to a particular project, workshop or conference, and do not often cover the labour costs of those activities. Any additional hardware purchases therefore eat into the funds which can be used to compensate the work of those involved. Avoiding buying new is not always an option however, when travel comes into play, as new circumstances require new kit like region specific sim cards, adapters and cables accidentally left unpacked or forgotten.

It should be noted that packing and handling these items comes with a certain element of risk. The Raspberty Pi is exposed to the rigours of travel and public transport, easy to crush or contaminate. We know that as a sensitive piece of technology, it should be treated with delicacy but the reality of picking up and moving it from one place to another, if not in short notice instead time-poorness, we often are less careful than we ought to be. The items constituting wiki4print have been variously gingerly placed into backpacks, wrapped in canvas bags, shoved into pockets and held in teeth. So far, nothing has broken irreparably, but we live in anticipation of this changing.

Raspberry pis are small single-board computers, built on a single circuit board, with the microprocessors, ports, and other hardware features visible [98]. Single-board computers use relatively small amounts of energy [99], particularly in comparison to server farms[100]. However, they are fragile, the operating system of our Raspberry pis run off SD cards and without extra housing are easy to break. They are by no means a standard choice for reliable or large-scale server solutions. However, their size and portability, as well as their educational potential is the reason we chose to host servpub.net websites on them.

The Raspberry Pis that host servpub.net and wiki4print.servpub.net were second-hand. So in many ways, we used Raspberry Pis because they are ubiquitous within the educational and DIY maker contexts within which many of us work. There are other open-source hardware alternatives that exist today like Libre Computer [101][102] and if we were to consider buying a new computer we would examine our choices around using a closed-source hardware option like a Raspberry Pi. The fact that our second-hand Raspberry Pis were close-to-hand within academic contexts reveals educational practices and concerns within Servpub.