No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (35 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="metadata"> | <div class="metadata"> | ||

== | <span id="Bilyana - Art-as-content"></span> | ||

== Art-as-content: a proposition for value shifts between the feed and the institution == | |||

'''Bilyana Palankasova''' | '''Bilyana Palankasova''' | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

The smart phone with its convergence of phone, camera, screen, and network fundamentally changed the landscape of media circulation and distribution and expanded art documentation beyond the realm of traditional cultural institutions (Sluis 2022, 27). Subsequently, social media and the proliferation of visual content came with curatorial limits and lack of control associated with the form of the feed (Wallerstein 2018). With its restrictive form, social media feeds allow for certain prescribed movements and ways of engagement. | |||

The interface has its own lexicon driven by verbs (likes, loves, shares) which relate to interaction design, as much as to traditional institutional needs of preserving, organising, categorising and archiving – and in this sense the experience of the feed draws on the vernacular of big tech as much as of cultural institutions (Hromack 2015). At the same time, there is a widespread tendency within art towards “the exhibition as a content farm” to describe the proliferation of artworks widely documented online – and often that digital quality of feed spam and the demand for attention outside of the institutional context “proves its very status as art” (Yago 2018). | |||

In this context, rather than thinking about crisis in political imagination, this proposition stands against the impossibility of new narratives within techno-capitalist content platforms. It proposes a reading of the relationship between form and artistic content production on social media as a performance of shifting values. Specifically, I position ''art-as-content'' on Instagram as a mechanisms of cultural innovation through Boris Groys’ theoretical lens. | |||

Groys believes that value is attached to cultural objects through “cultural archives” – public institutions such as museums, universities, libraries, archives etc. which structure and store cultural works in a particular value hierarchies. At the same time, cultural innovation is always achieved via a rational and “strategic” synthesis of “positive” and “negative adaptation” to the valorised cultural tradition (Groys 2014, 108) – the new is still defined in its position against the old. Groys suggest that there is a shifting value line separating the archives from the “profane realm” – what is thought to be vulgar, valueless, or extra-cultural (Groys 2014, 64). | |||

In this conceptual framework, the process of cultural innovation as the production of the new (not as the new per se) is realised by movement from the profane space (“a reservoir for potential new cultural values”) to the archives themselves. In a sense, a process of institutionalisation through the mobility of values. Groys exemplifies this with the ready-made and its historical revaluation to become a dominant aesthetic (Groys 2014, 95). He observes that this process changes and modifies value hierarchies in the archives through the valorisation of the profane (Groys 2014, 147). | |||

Following this conceptual framework, "art-as-content" represents a shifting value line between "content" (as the profane and vulgar feed) and the institutional cultural archive (or institutionalised practices) and therefore engages a process of re-valuation of content. This could be exemplified in two ways: | |||

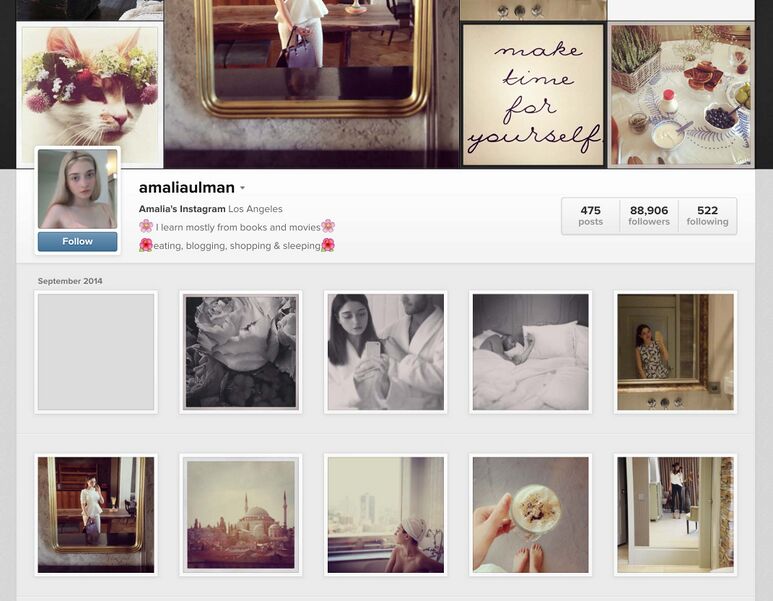

Firstly, "art-as-content" by the feed being incorporated in artistic production. By its integration into artistic performances the feed becomes a meaningful cultural objects, a sort of ready-made, a form for the presentation of artistic work. A key work to illustrate this would be Amalia Ulman's ''Excellences & Perfections -'' a performance of consumerist lifestyle on Instagram and Facebook. | |||

[[File:Excellences & Perfections.jpg|thumb|773x773px|Amalia Ulman, ''Excellences & Perfections'', 2014. Screenshot of [https://webenact.rhizome.org/excellences-and-perfections/20141014150552/http://instagram.com/amaliaulman Rhizome webenact].]] | |||

Secondly, "art-as-content" by the feed becoming an archive in itself through the use of the profile page by artists as a self-curated archive and a grid for documenting work. On Instagram in particular, the profile feed has become a publishing space for sharing art documentation. From an artist's perspective, this allows for agency in constructing one's narrative as an archive of curated documents, which exists outside of traditional cultural institutions and challenges traditional thresholds of valuation.<ref>An earlier version of this text focused solely on "art-as-content" in the form of art documentation published by artists on Instagram as a form of record keeping and public archive. While acknowledging the history and significance of performance art on social media and its relationship to discourses around documentation of performance more widely, I wanted to discuss a single instance of art documentation online as a self-archive and didn't plan on including social media performance as an instance illustrating my argument. Subsequently, after comments from peers, I decided to widen the scope of the discussion by differentiating between two kinds of "art-as-content".</ref> | |||

<div id="bilyana-images"><ul> | |||

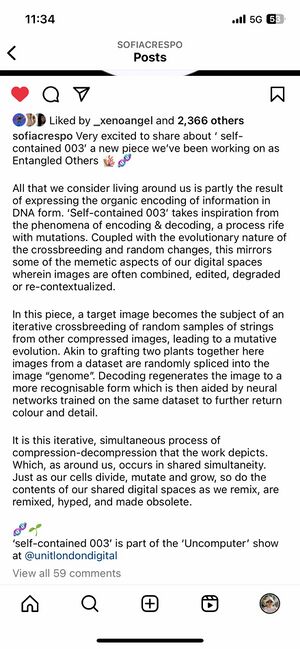

<li style="display: inline-block; vertical-align: top;"> [[File:SofiaCrespo1.jpg|thumb|Sofia Crespo, s''elf-contained 003,'' Screenshot of an Instagram reel published on 7 Oct 2023.]] </li> | |||

<li style="display: inline-block; vertical-align: top;"> [[File:SofiaCrespo caption.jpg|thumb|Sofia Crespo, ''self-contained 003,'' 2023. Screenshot of caption for Instagram reel.]] </li> | |||

</ul></div> | |||

Thinking through these two re-evaluations of content within cultural production proposes a shift in the relationship between content production and artistic representation and through the lens of cultural innovation suggests potential for content as both a tool and object of research in the historicisation of creative practices. | |||

<references/> | |||

<noinclude> | |||

[[Category:Content form]] | [[Category:Content form]] | ||

</noinclude> | |||

Latest revision as of 11:20, 7 February 2024

The smart phone with its convergence of phone, camera, screen, and network fundamentally changed the landscape of media circulation and distribution and expanded art documentation beyond the realm of traditional cultural institutions (Sluis 2022, 27). Subsequently, social media and the proliferation of visual content came with curatorial limits and lack of control associated with the form of the feed (Wallerstein 2018). With its restrictive form, social media feeds allow for certain prescribed movements and ways of engagement.

The interface has its own lexicon driven by verbs (likes, loves, shares) which relate to interaction design, as much as to traditional institutional needs of preserving, organising, categorising and archiving – and in this sense the experience of the feed draws on the vernacular of big tech as much as of cultural institutions (Hromack 2015). At the same time, there is a widespread tendency within art towards “the exhibition as a content farm” to describe the proliferation of artworks widely documented online – and often that digital quality of feed spam and the demand for attention outside of the institutional context “proves its very status as art” (Yago 2018).

In this context, rather than thinking about crisis in political imagination, this proposition stands against the impossibility of new narratives within techno-capitalist content platforms. It proposes a reading of the relationship between form and artistic content production on social media as a performance of shifting values. Specifically, I position art-as-content on Instagram as a mechanisms of cultural innovation through Boris Groys’ theoretical lens.

Groys believes that value is attached to cultural objects through “cultural archives” – public institutions such as museums, universities, libraries, archives etc. which structure and store cultural works in a particular value hierarchies. At the same time, cultural innovation is always achieved via a rational and “strategic” synthesis of “positive” and “negative adaptation” to the valorised cultural tradition (Groys 2014, 108) – the new is still defined in its position against the old. Groys suggest that there is a shifting value line separating the archives from the “profane realm” – what is thought to be vulgar, valueless, or extra-cultural (Groys 2014, 64).

In this conceptual framework, the process of cultural innovation as the production of the new (not as the new per se) is realised by movement from the profane space (“a reservoir for potential new cultural values”) to the archives themselves. In a sense, a process of institutionalisation through the mobility of values. Groys exemplifies this with the ready-made and its historical revaluation to become a dominant aesthetic (Groys 2014, 95). He observes that this process changes and modifies value hierarchies in the archives through the valorisation of the profane (Groys 2014, 147).

Following this conceptual framework, "art-as-content" represents a shifting value line between "content" (as the profane and vulgar feed) and the institutional cultural archive (or institutionalised practices) and therefore engages a process of re-valuation of content. This could be exemplified in two ways:

Firstly, "art-as-content" by the feed being incorporated in artistic production. By its integration into artistic performances the feed becomes a meaningful cultural objects, a sort of ready-made, a form for the presentation of artistic work. A key work to illustrate this would be Amalia Ulman's Excellences & Perfections - a performance of consumerist lifestyle on Instagram and Facebook.

Secondly, "art-as-content" by the feed becoming an archive in itself through the use of the profile page by artists as a self-curated archive and a grid for documenting work. On Instagram in particular, the profile feed has become a publishing space for sharing art documentation. From an artist's perspective, this allows for agency in constructing one's narrative as an archive of curated documents, which exists outside of traditional cultural institutions and challenges traditional thresholds of valuation.[1]

Thinking through these two re-evaluations of content within cultural production proposes a shift in the relationship between content production and artistic representation and through the lens of cultural innovation suggests potential for content as both a tool and object of research in the historicisation of creative practices.

- ↑ An earlier version of this text focused solely on "art-as-content" in the form of art documentation published by artists on Instagram as a form of record keeping and public archive. While acknowledging the history and significance of performance art on social media and its relationship to discourses around documentation of performance more widely, I wanted to discuss a single instance of art documentation online as a self-archive and didn't plan on including social media performance as an instance illustrating my argument. Subsequently, after comments from peers, I decided to widen the scope of the discussion by differentiating between two kinds of "art-as-content".