| Line 171: | Line 171: | ||

== DOMESTIC/PRIVATE SPACES == | == DOMESTIC/PRIVATE SPACES == | ||

[[File:ServpubFlat.jpg|alt=Screenshot from a Signal chat of a bedside table with items. Text reads: "This is my current bedside table while I'm out of my flat. I feel it's very on brand - server, antidepressants, mouth guard, switch, cables" Three laughing crying emojis in response. Another member of the chat replies "https://servpub.net/ is down atm tho"|center| | [[File:ServpubFlat.jpg|alt=Screenshot from a Signal chat of a bedside table with items. Text reads: "This is my current bedside table while I'm out of my flat. I feel it's very on brand - server, antidepressants, mouth guard, switch, cables" Three laughing crying emojis in response. Another member of the chat replies "https://servpub.net/ is down atm tho"|center|frameless]] | ||

Revision as of 17:44, 11 September 2025

Platform infrastructure

Winnie, Katie, Becky, Batool

Introduction

Wiki4print, the raspberry pi which hosts https://wiki4print.servpub.net/ travels with us [1]. We have physically constructed our network of servers so that we can keep it's hardware by our side(s) as we use it, teach and experiment with it, and activate it with others. This chapter will consider the materiality of our particular network of nodes, our reasoning for arranging our infrastructure in the way we have and what it means to move through the world with these objects. By considering our movement from one place to another we can begin to understand how an ambulent server allows us to locate the boundaries of the software processes, the idiosyncrachies of hardware, the quirks of buildings and estates issues, and how we fit into larger networked infrastructures. We will consider how we manage departures, arrivals, and points of transcience, reveals boundaries of access, permission, visibility, precarity and luck. This proximity to the server creates an affective relationship, fostering responsibility and care for these precarious objects, allowing us to engage critically with the physicality of digital platforms and infrastructures. In contrast to vast, impersonal cloud systems, our mobile server foregrounds flexibility, rhythm, and scale—offering a bodily, hands-on experience that challenges dominant industrial models.

In this chapter we will explain our decision to arrange our physical infrastructure as mobile and in view. To do this we will map our collective experiences in a series of types of space. These spaces are reflective of our relative positions as artist*technologist*activist*academic (delete as appropriate):

- THE PUB / PUBLIC SPACES (maybe add this? e.g. 8M / the social origins/elements?)

- EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS (+history, eduroam,ctp,aarhus, cci, lsbu etc) (overview)

- SUITCASES AS SPACE: (hardware)

- CULTURAL/SEMI-PUBLIC SPACES (more on physical layer of the internet)

- DOMESTIC/PRIVATE SPACES (hardware maintenance and care)

- NATIONS / TRAVEL

- WORKSHOPS AS SPACE (workshopping as a methodolgy, a server runs on a computer)

//[Katie: here are some notes that we talked about last time about why matters for having a mobile server, which I think might be good to use for contextualizing the intro for this chapter as a framing...this affective dimension.

- katie: proximity and affective relation with objects - get to the thing -> responsonsibliity -> precariy of objects -> reporting - becky: platform - what is it about -> physicality > help us to talk about the affect > critque of cloud and reality? what does it mean by unplug, put into the netwirj - fexibley space , wat doese it allow us?? - rhtythms into ifrastructre - scale -> different dynamics endless, massive stack (smaller than our average computer, beyond industry standard), bodily way //]

By situating our mobile server within these diverse spatial contexts, we illuminate the complex interplay between technology, place, social and embodied experience, advancing a critical discussion of infrastructure that foregrounds the materiality of data, software, and social-technical processes alongside tangible infrastructure. This perspective brings us to an essential question: why does the mobility of servers matter?

Travelling server space: Why does it matter?

As briefly mentioned in Chapter 1, one of the key inspirational projects for ServPub is ATNOFS (A Traversal Network of Feminist Servers), a collaboration of six collectives and organisations researching intersectional, feminist, and ecological server infrastructures for their communities. Many precedents have contributed to the exploration of feminist servers, including the Feminist Server Manifesto developed during a workshop hosted by Constant in 2013 [2], and Systerserver, which has been active since 2005 [3]. While there is significant focus on care, labor conditions, and maintenance, the technical infrastructure remains largely hidden from the general public as servers are fixed in location and often distant from the working group. We often perceive servers as remote, and large-scale entities, especially in the current technological landscape where terms like "server farms" dominate the discourse.

Attending the ATNOFS meeting was both helpful and rewarding, offering a tangible experience of what a server looks and feels like by working together. Contrary to the common perception of servers as large and remote, they can be as small as the palm of your hand and in proximity. Rosa is considered as a travelling server which afforded collaborative documentation and notetaking at various physical sites where the meetings and workshops were taken place in 5 different locations throughout 2022. In addition Rosa is also part of the self-hosted and self-organised infrastructures of ATNOFS, engaging "with questions of autonomy, community and sovereignty in relation to network services, data storage and computational infrastrucutre" [4]. The project is highly influencial as it encourages ServPub members to rethink infrastructure—not as something remote and distant, but as something tangible and self-sustained. It also highlights the possibility of operating independently, without reliance on big tech corporations. While most feminist server and self-hosting initiatives have emerged outside of London, we are curious about how the concept of traveling physical servers could reshape a vastly different landscape—one defined by critical educational pedagogies, limited funding, and the pressures of a highly competitive art and cultural industry in the UK. The first consideration is skills transfer—fostering an environment where technical knowledge and open-minded thinking are recognized and encouraged, enabling deeper exploration of infrastructure. This is also where the London-based collective In-grid, comes into the picture of ServPub.

THE PUB / PUBLIC SPACES

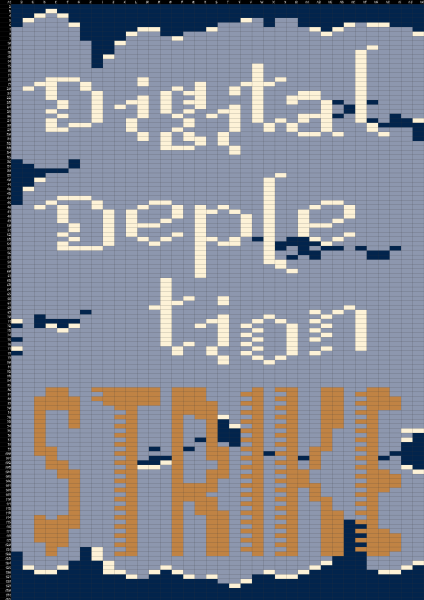

Networking as a space: Call for a Counter Cloud Action Day

On the 8th of March 2023 (8M), an international strike called for a "hyperscaledown of extractive digital services" [5]. The strike was convened by numerous Europe-based collectives and projects, including In-grid, Systerserver, Hackers and Designers, Varia, The Institute for Technology in the Public Interest, NEoN, and many others. This day served as a moment to reflect on our dependency on Big Tech Cloud infrastructure—such as Amazon, Google, and Microsoft—while resisting dominant, normative computational paradigm through experimentation, imagination, and the implementation of self-hosted and collaborative server infrastructures.

To explicate this collective action, the call's website is hosted and asynchronously maintained by a network of networks, technically known as a Webrings, especially popular in the 1990s, are decentralized, community-driven structures that cycle through multiple servers. In this case, 19 server nodes—including In-grid—participate, ensuring the content is dynamically served across different locations. When a user accesses the link, it automatically and gradually cycles through these nodes to display the same content. Webrings are typically created and maintained by individuals or small groups rather than corporations, forming a social-technical infrastructure that supports the Counter Cloud Action Day by decentralizing control and resisting extractive digital ecosystems.

On the evening of 8M, many of us—individuals and collectives based in London— gathered at a pub in Peckham, South London. The location was close to the University of the Arts London where some participants worked. What began as an online network of networks transformed into an onsite network of networks, as we engaged in discussions about our positionality and shared interest. This in-person meeting brought together In-grid, Systerserver and noNames collectives, shaping a collaborative alliance focused on local hosting, small scale infrastructure for research, community building, and collective learning.

EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS

Critiques of Institutional spaces

Within this context of decentralized and community-driven digital infrastructures, it is impossible to overlook the contrasting landscape of educational institutions. These institutions operate within vast, standardized, and often centralized infrastructures, which present a different set of challenges and critiques. For example, many contributors to this book involved in organizing and participating in the Minor Tech workshop[6] in London in 2023, which explored notions of 'scale' in technology alongside the 2023 Transmediale festival. The workshop explored and challenged universal ideals of technology and the problems of scale, including big data, machine learning, artificial intelligence, cloud computing, and blockchain mining. It also examined their connections to the global organization of labour, resource extraction, exploitation, energy consumption, and related issues.

Within educational and instituional settings, many of us operate within big infrastructures that are standardized, centralized, and normative—for example, the widespread use of Microsoft 365 for organizing daily tasks, meetings, routines, and documents through SharePoint, a cloud-based collaboration and document management platform for team collaboration, document storage, and intranet services. Similarly, the institutional networked infrastructure Eduroam (short for 'Education Roaming') provides global access, secure connections, and convenience. However, it also comes with limitations and challenges, including IT control and network restrictions, such as port blocking to prevent unauthorized or high-bandwidth usage, as well as traffic monitoring under strict privacy policies. This protective environment inevitably trades off autonomy and user agency, making it difficult to engage with the infrastructure beyond mere convenience and efficiency.

For instance, carry out projects like self-hosting servers with customized software within these infrastructure is highly challenging. One such project, like CTP (Critical Techncial Practice) server [7], hosted at Aarhus University but maintained by academic staff, has faced various obstacles—from negotiating a more autonomous server space to enabling remote login for external collaborators[8]. When systems become standardized, everyone accesses them in the same way, leaving little to no room for alternative approaches to learning. For researchers, teachers, students, and those who view infrastructure not merely as a tool for consumption and convenience but as an object of research and experimentation, opportunities to engage with it beyond predefined uses are limited. This lack of flexibility makes it difficult to explore and understand the black box of technology in ways that go beyond theoretical study. The question then becomes: how can we create 'legitimate' spaces for study, exploration and experimentation with local-host servers and small scale infrastructure within institutions?

Institutional intervention: software installation

Creating legitimate space to Introduce alternative software in a university setting can be challenging. Our engagement with digital infrastructure extends beyond efficiency and productivity— it involves critically examining and deconstructing technology as part of our pedagogical approach. However, university IT departments may not always recognise that software fundamentally shapes how we see, think, and work — a key aspect of teaching and learning that goes beyond simply adopting readily available tools. A case in point is our request to implement Etherpad, a real-time collaborative writing tool that is free and open source (FLOSS), widely used by grassroots communities for internal operations and workshop-bsed learning. Unlike mainstream tools, Etherpad facilitates shared authorship and co-learning, aligning closely with our pedagogical values.

In advocating for its use, we found ourselves having to strongly defend both our choice of tools and the reasons why alternatives like Microsoft Word were insufficient. IT initially questioned the need for Etherpad, comparing it to other collaborative platforms such as Padlet, Miro, and Figma. Their priority, we learned, was finding software that integrated easily with Microsoft 365 — a choice driven by concerns around centralised management and administrative efficiency, rather than pedagogical value or student experience. When we highlighted Etherpad’s open-source nature — and the opportunities it offers for adaptation, customisation, and community-driven development — we also pointed to how this reflects our teaching ethos: fostering critical engagement and giving students agency in shaping the tools they use. Despite this, we were still required to further justify our case by demonstrating how Etherpad supports teaching in ways that alternatives like Google Docs do not. It ultimately took nearly a year to establish this as a legitimate option. The broader point is that introducing non-mainstream, non-corporate software into institutional settings demands significant additional labour — not only in time, but also in the ongoing work of justification, negotiation, and communication.

Institutional intervention: Self-hosted infrastructure

The ServPub project began with the desire to create alternative software and infrastructure, emphasizing self-hosting and small-scale systems that enable greater autonomy. One of the goals is to explore what becomes possible when we move away from centralized platforms and servers, offering more direct ways to access the knowledge embedded in infrastructure and technology. Developing alternative approaches requires a deeper understanding of technology—beyond simply using them from well-defined, packaged and standardized solution.

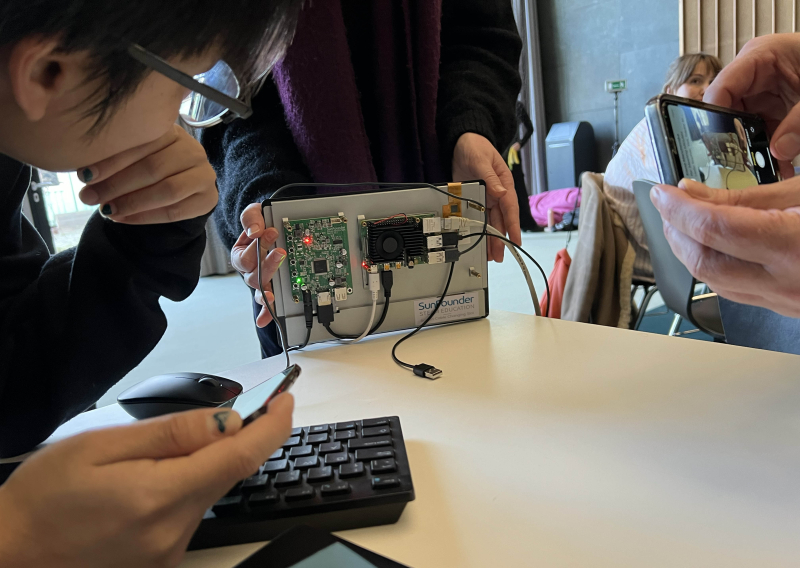

During our first ServPub workshop[9] at a university in London in 2023, where we configured the server using a Raspberry Pi, we encountered these constraints firsthand: the university’s Eduroam network blocked access to the VPN server running on the Pi. We required a VPN (Virtual Private Network) because it allows us to assign a static IP address to the server and make the hosted site publicly accessible beyond the local network (more details about VPN are discussed in the next chapter). However, institutional network security policies often block VPN traffic, as VPNs can obscure user activity, bypass filtering systems, and introduce potential security risks. To maintain control, network administrators typically restrict the protocols and ports used by VPNs, resulting in such blocks within Eduroam environments.

These restrictions create significant challenges for experimental and self-hosted projects like ours. More critically, Eduroam’s technical architecture and policies embed institutional control deeply into network access. While it is designed to provide secure and seamless global connectivity through standardized authentication protocols, it also enforces user dependency on institutional credentials and network policies that limit experimentation and autonomous infrastructure use. Our experience with Eduroam exemplifies these challenges, highlighting the broader tensions between institutional infrastructures and the desire for more self-determined, flexible technological practices.As a result, we resorted to sharing one of the organizers’ personal hotspot connections (using a mobile data network), which itself was limited by a 15-user cap on hotspot sharing. While this was not an ideal solution, at that point in time it served as a necessary workaround that allowed the Pi server to connect to any available internet network, even when held by someone without access to an institutional Eduroam account.

This experience of navigating institutional constraints points to the significance of mobility and portability in our approach. Carrying our server with us enables a form of technological autonomy that challenges fixed infrastructures and their limitations. This brings us to consider the physical and conceptual implications of portability—what it means to live and work with servers inside suitcases, and how these objects become mobile spaces in their own right.

SUITCASES AS SPACE

We have referenced the fact that our server can be brought with us to visit other places. What that means in practice is a repeated unplugging and packing away of objects. We unplug the server, literally and figuratively, from the network. In the case of wiki4print, the node unplugged, sans-electricity, sans-network is:

- Raspberry pi

- SD memory card

- 4G dongle and sim card (pay-as-you-go)

- Touch Screen

- Mini cooling fan

- Heat-sink

- Useful bits and pieces (mouse, keyboard, power/ethernet/hdmi cables)

These items have been variously bought, begged and borrowed from retailers, friends and employers. We have avoided buying new items where possible, opting to reuse or recycle hardware where possible. We try to use recycled/borrowed items for two primary reasons. First, we are conscious of the environmental impact of buying new equipment, and are keen to limit the extent to which we contribute to emissions from the manufacturing, transportation and disposal of tech hardware. Secondly, we are a group working with small budgets, often coming from limited pots of funding within our respective institutions. These amounts of funding are most often connected to a particular project, workshop or conference, and do not often cover the labour costs of those activities. Any additional hardware purchases therefore eat into the funds which can be paid to compensate the work of those involved. Avoiding buying new is not always an option however, when travel comes into play, as new circumstances require new kit like region specific sim cards, adapters and cables accidentally left unpacked or forgotten.

It should be noted that packing and handling these items comes with a certain element of risk. The raspbery pi is exposed to the rigours of travel and public transport, easy to crush or contaminate. We know that as a sensitive piece of technology, it should be treated with delicacy but the reality of picking up and moving it from one place to another in, if not short notice instead time-poorness, we often are less careful than we ought to be. The items constituting wiki4print have been variously gingerly placed into backpacks, wrapped in canvas bags, shoved into pockets and held in teeth. So far, nothing has broken irreparably, but we live in anticipation of this changing.

Why Raspberry Pi?

Raspberry pis are small single-board computers, built on a single circuit board, with the microprocessors, ports, and other hardware features visible [10]. Single-board computers use relatively small amounts of energy [11], as compared to standard personal computers and server farms (refs). However, they are fragile, the operating system of most Raspberry pis run off small SD cards and without extra housing they are easy to break. They are by no means a standard choice for reliable or large-scale server solutions. However, their size and portability, as well as their educational potential is the reason we chose to host servpub.net websites on them.

The Raspberry pis that host servpub.net and wiki4print.servpub.net were second-hand. So in reality, we used Raspberry Pis because they are ubiquitous within the educational and DIY maker contexts within which many of us work. There are other open-source hardware alternatives that exist today like Libre Computer [12][13] and if we were to consider buying a new computer we would examine our choices around using a closed-source hardware option like a Raspberry pi.

Founded in 2008, the Raspberry Pi Foundation’s mission was to make low-cost computers and to increase computer literacy. Although Raspberry Pis are comparatively not that cheap anymore (compared to some PCs), making computing physical can make computing concepts more accessible and engaging (ref). Raspberry Pis were inspired by BBC microbits (ref?), which were first created in the 1980s through a BBC collaboration with Acorn computers, their mission was to increase computer literacy and they continue to follow the principle of making computing physical[14] [15]. Servpub in many ways sits within this educational context, the fact that our second-hand Raspberry Pis were close-to-hand within educational contexts being the primary example. The desire to bring the server as an object into the workshop as space sits within this wider tradition of making computing physical and visible for educational purposes.

A common conceptualisation of the internet is of a remote untouchable thing, a server farm or in the worst case some nebulous cloudy concept. Being able to point at an object helps us materialise the network, for example being guided to point to a microwave antennae perched on top of a building as can be seen in Ingrid Burrington’s Networks of New York illustrated field guide to internet infrastructure in the city [16]. Using a small-scale computer allows us to bring the server into proximity with bodies in workshops. The visibility of the guts of the machine, for example exposed ethernet ports, enables a different type of relational attention to the hardware of the server.

CULTURAL/SEMI-PUBLIC SPACES

Up to the point of writing, our Wiki4Print[pi] has been a physical presence at several public workshops and events/interventions. Although in many (if not all) cases, it would be more practical and less effort to leave the hardware at home, we opt to bring it with us, for the reasons outlined above. By dint of our artist*sys/admin*academic situations, the pi has visited several of what we are defining as cultural spaces. We are using this term to describe spaces which primarily support or present the work of creative practicioners: museums, galleries, artist studios, libraries. This definition is not perfect, and obscures a lot of factors which we feel are pertinent to this discussion. We are conflating publicly funded institutions with privately rented spaces, spaces that are free to enter with others that have partial barriers like membership or ticketing. However, we feel that for our purposes here, these comparisons, although imperfect allow us to see common issues. As with our entrances and exits from institutional spaces (universities), domestic locations and moments traveling we need to spend some time feeling out the material conditions of the space, and the customy practice in, and idiosyncracies of, that space. Not all two cultural spaces are built the same, as no two homes are the same.

We'll tell you about two spaces to explain what we mean.

SPACE 1. STUDIOS: An arts space run by a charity, based in a meanwhile use [17] building. The building contains rented studios which are used by individual artists and small businesses, a cafe and performance space, and gallery space open to the public. The longevity of the space is precarious due to the conditions of a meanwhile use tenancy. The building itself is only partially maintained as it is intended for demolition by the developers who own the site. Plumbing issues, dodgy lifts and non-functional ethernet ports and sockets abound. The space is based in the UK.

SPACE 2. MUSEUM: A center for contemporary arts, publicly funded by the federal government. The space hosts art exhibitions, theater and performance, films, and academic conferences. It also contains cafes and shops, and is generally open to the public, with some ticketed events. This space is in Germany.

For now we will refer them the two spaces as STUDIOS and MUSEUM.

These spaces are demonstrably quite different, in their scale, security and publicness. That being said there are common experiences when arriving in cultural spaces with a mobile server. We need to feel out the location every time, understand levels of access, the policies and politics of these spaces, and of the duty of care/legislative duties each institution needs to respect. We may have developed our protocols of working, but these cannot be impressed upon other spaces indiscriminately, we need to acknowledge that we are sharing this space with its caretakers, and also with other creative groups with their own needs and working practices, and the wider public who may be impacted and interested in our presence, or who may not be aware we are sharing the space at all.

The most pressing issue is often access to an internet connection. As we have outlined in [chapter x/section y], our network of nodes are connected to each other using a VPN. In our case, the VPN network requires access to the internet to encrypt and route data through its servers. Additionally, two of our nodes (wiki4print and pubdoc), serve up public webpages (wiki4print.servpub.net and servpub.net) and when offline these sites cease to be accessible. [FACT CHECK THE VPN PART to make sure I'm describing this accurately]. Getting internet access may appear to be a simple enough problem to solve, being as we are in cultural spaces which often have public wifi available, but often it becomes more convoluted.

As we discuss in further detail in the section on educational institutions, some internet networks block all VPNs. Although this particular issue was not apparent in this particular STUDIO or MUSEUM, it is not uncommon for a public wifi network to block VPNs in order to control access, or for security reasons. For example, some organisations may block VPNs to maintain control over their network traffic, or to try to limit who has access. VPNs mask the IP addresses of users, and so by removing that option, institutions have greater insight into who is accessing their networks and what they are doing while connected. Additionally, although this is not an issue we directly encountered, some national governments block or restrict VPN use in order to impose state censorship and reduce individual privacy and agency, although it's often framed by the powers that be as a measure to maintain national security or prevent cybercrime ( https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10606-022-09426-7, Russia, China, Turkey - is this a bit of a fleeting mention of a massive issue? How best to frame this point with the appropriate weight, reference Winnies Unerasable Characters?).

All that being said, in our experience, cultural spaces are more personal and negotiable than Educational Institutions, despite the possibility for equal levels of government oversight and private interests. We have found that Cultural Spaces have become intrinsic to our ability to experiment publicly and accessibly.

The most profound difference we have observed is the ability to establish a personal connection with individuals in order to make something happen, or adjust/remove a factor which is impeding us (locked doors, firewalls). In short, in cultural spaces, it's easier to find people, whereas we have found that (at least UK based) Universities adopt more detached processes. We have found that it is becoming increasingly difficult to find faces on campuses, whereas in cultural spaces we have found it easier to locate: technical staff, other tenants, communities of users, visitor coordinators. Often, in Universities we find help-desk ticketing systems. This is of course a generalisation, and is not a reflection of the people labouring behind those ticketing systems, moreso it is of the changing nature of work and neoliberalisation of higher education systems.

but comes with more emotional labour, hiccoughs and weirdnesses

We dont need to justify our choices (we can make weird choices and people are like shit ok youre a client and an artist, here to facilitate), we dont need to fight for legitamate space, more fragile.

Flexible but also messy

do we need to compare the spaces more? Does it make sense to describe them or do we need to change the tone so we are using them both as examples or the same things?

* VPN blocks - using mobile hotspot to bypass institutional barriers

* Wifi strength, coverage over large buildings, connections with 100s/1000s of people

* Routers - where are they?

* Reliance on systems we cannot directly troubleshoot - precarious spaces (studio space in SET) where there may not be staff onsite to help, "parasitic" -- negotiatiing with different networks (power dynamic / security)

* Ethernet - often disconnected!,

* MAC addresses (unclear on this - ask B why this was included)

* Estates issues: (broken?)ethernet ports, working plugs, access to extensions, locked doors, opening hours, previous bookings, cleaning regimens, central heating (or lack there of), security (theft), furniture.

negotiation of being portable but who has the permissions.

Transmediale the connectivity not working when we arrived, as an example.

Within instituitions, the need to use mobile hotspots to bypass the institutional barriers. Refer to the constraints of educational spaces.

"parasitic" -- negotiatiing with different networks (power dynamic / security)

- - Public institution/cultural spaces (museum/HKW at TM/SET), EASST

Once connected to the VPN, problematics and politics of:

- - Accessing the wider internet from different spaces

- - Physical layer of network infrastructure

- - Routers / Wi-fi / ethernet / MAC addresses ?

https://ci.servpub.net/in-grid/collective-infrastructures

wiki4print was originally at SET Studios in Woolwhich. The building was originally (what?) then it was an HMRC building (insert full history), it is now maintained by the Arts Charity SET which emerged out of squat culture in London. The use of meanwhile space (definition?) within the arts sector in London is closely tied into wider property development crises, where more and more artists are reliable on institutions that exist in the margins[18]. The reality of having a studio within a meanwhile space is that much of the infrastructure is crumbling. When In-grid first set up the Raspberry pis the hope was to host them in an art studio at SET, but it quickly became apparent that it was not viable, the ethernet ports in the room were not functional, the wi-fi was not reliable and the team maintaining the building are primarily artists themselves rather than corporate service providers. In the lead up to the Content/Form Transmediale workshop the pi kept crashing and going offline. We moved it to avoid these issues in the middle of a co-working session with multiple collectives so as to stick to the timeline.

- moved from domestic spaces up here. Difference in approach in the section Cultural / Semi-public spaces and the rest of the chapter. Rest of the chapter is naming institutions, places and people (which feels more in keeping with radical referencing?). Should we adjust to mention SET and Transmediale explicitly? Could be nice to include some of the history of why we are in those spaces?

DOMESTIC/PRIVATE SPACES

The wiki4print pi has ended up living in a house of an In-grid member in South London. How it came to be there was a result of the needs of caring for a temperamental Raspberry pi in a temperamental meanwhile space (SET studios). However, its particular journey through London and where it has landed was as much to do with the material constraints of internet access as it was to do with the needs of working in a collective. Passing hardware from hand to hand across London became a force that determined the material shape of the network: last minute plans, emergencies, the demands of work schedules, holidays, illness and commute times all played a part in the movement of the hardware.

On one occasion In-grid, NoNames and CC were engaging in a working session to resolve an important functionality of https://wiki4print.servpub.net/. The pi kept going offline and needed someone on hand to physically reset the device or reconnect to the internet. We had to pause the workshop, while the pi was physically moved from SET studios to the house of an In-grid member. Why to that person's house in particular? The house was the closest to the studio and on the way to work for the other In-grid member. While others took a tea break the server was handed from hand to hand at a doorstep in East London on a rainy grey day, stress was shared, the pi was re-booted, the workshop continued. Moreover, the server was about to travel to Germany for a conference and this necessitated it being physically accessible to a member of In-grid who was travelling to Germany.

We thought the pi kept going offline because the SET wi-fi was bad, this was one of the problems, but it was also a red herring. We discovered there was another issue while the pi was in its new home in East London (temporarily living under a bed so the ethernet cable could reach it). Through the process of being able to debug at any hour (lying on the floor beside the bed) we were able to discover that problems with accessing the pi online were due to the Raspberry pi overheating, freezing and shutting down processes which would take it offline. We bought a heat sink and fan for the pi, and from then on it worked reliably in all locations.

Maintaining server hardware in a domestic space or outside the context of a server farm (small or large) becomes an act of providing care at odd hours. Maintenance invites the rhythms and bodies of others into the material realities of the network. Cleaning the cat hair out of the fan of the raspberry pi or plugging in the pi because a guest did some hoovering and didn't realise what they were unplugging. When someone from the wider Servpub group reports that wiki4print is down on our mailing list, an In-grid member replies back with the latest anecdote about what has happened, providing a remote window into the lives and rhythms of bodies and hardware in spaces.

NATIONS/TRAVEL

So far, this writing has detailed the cultural, educational and domestic spaces that have housed the server at different times and for different reasons. Sometimes out of convenience, sometimes as an educational tool, sometimes as evidence that indeed a server can be built outside its farm and sometimes still we frankly brought the server along just-in-case. Cutting through all these spaces was the core attribute of this server being ambulant, which was a need highlighted and inspired by the Rosa project to which a significant portion of Servpub is owed. This need for mobility and reachability revealed the seams between what would otherwise be seamless transitions across different spaces with different [politics]. Perhaps most glaring of these seams were none other than the European borders themselves.

Though travelling with the hardware did little more than raise eyebrows from airport security staff, it was the crossing of a less ambulant person that almost prevented us from taking the server to Amsterdam in the summer of 2024 for the EASSSST/4S conference. The conference was to be attended by a small sub-group of the Servpub team, to present the project and host a hands-on workshop through the server. Batool, who was part of this group, had packed the hardware in their bag after having retrieved it from Becky for the purpose of this trip. Batool was/is (at the time of writing) holding refugee status in the UK and were allowed to travel within Europe with a UK issued Travel Document. But there were exceptions. Should we use individuals' names? See above I changed it to say In-grid member which is maybe confusing, but maybe not? Something to discuss.

The conference was in Amsterdam to which Batool was allowed to travel, and the group were taking the Eurostar straight to their destination without making any stops. However, they were about to traverse a particularly absurd part of the French law pertaining to the movement of refugees. As the officers at the Eurostar terminal explained, it was because the train will be crossing over French territory, for which Batool would need a visa, that they could not be allowed on the train. The fact the the destination was not in France and that the train was not due to make any stops in France did not matter. In fact, that argument only presented the more absurd speculation that in the case of an emergency stop or break-down of the train in France, they would be in breach of the visa law which and that was even more justification for refusing them entry to the train. Four hours later, George and Katie were on their way and the server was still in London with Batool.

The solution was to take a direct flight to Amsterdam (and hope that it wouldn't emergency-land or break-down over France) which Batool booked for the next day. But having had no funding for this trip, and not being able to refund the train ticket, this was perhaps the most jarring spatial transition during this project. Not only did it reveal the limits of mobility and access, it also revealed the limits of collectivity and radical infrastructures. There was only so much infrastructure to radicalise when the political structures themselves oppressive and only getting worse.

WORKSHOP AS A SPACE (ending / conclusion)

Creating a theory of space, a unifying conceptual framework for why we want to discuss these forms of space and how.

- Creating a space in a workshop, creating

- need to be with it to work - proximity to it to fix it

A server runs on a computer. By bringing the pi in person to teaching moments, it allows us to discuss ideas around the physicality of a server and caring for a server. There is trust and intimacy in proximity. This allows us to demystify network infrastructure.

Plugging it in:

- - Start with the impact of physicality, being in the same room as the hardware, being able to point to it in the corner of a room. Understanding the distinction between software and hardware. Setting up Hardware, what is an operating system Linux (why Linux):

- + further links to Raspberry Pi

- - Local Area Network

- - Physical layer of network infrastructure?

- - Routers / Wi-fi / ethernet / MAC addresses ?

- - Software / Internet Protocol layer

- - TCP / UDP / ports / IP Address ?

- - Protocols:

- - SSH (to enable networked/remote collaboration, I'm not sure going into collaboration here is the right thing to do, maybe more for praxis doubling? More writing on this in the pad)

- https://www.raspberrypi.com/documentation/computers/remote-access.html#ssh

- - Default Password Access. Basics of SSH + command line: navigating around a computer, installing software etc.

- - Setting up SSH keys per User ?

- - TMUX ?

- - HTTP

- - Default set up on a pi?

- - Setting up a server with Nginx

- - the browser: accessing a website on the LAN

Glossary -> Can we make a glossary for the technical terms...

Technical Writing / Structure for what to potentially include in this chapter

- Hardware (why pi)

- - Why Raspberry Pi

- - Setting up Hardware:

- + further links to Raspberry Pi

- Remote Access to Hardware over a local network (workshop)

- - What constitutes a local area network LA

- - Physical layer of network infrastructure?

- - Routers / Wi-fi / ethernet / MAC addresses ?

- - Software / Internet Protocol layer

- - TCP / UDP / ports / IP Address ?

- (Network Infrastructure chapter has some detail about lan/wan/van already + history and politics of IP Addresses IPv4 and IPv6, they touch on Static IP addresses) https://wiki4print.servpub.net/index.php?title=Chapter_2b:_Server_Issues:_Networked_Infrastructure

- What Protocol stack or internet infrastructure model do we want to use and what are the politics of that? Not sure what protocol stack is in Network Infrastructure Chapter (image of the hourglass). OSI or Internet Protocol Suite (TCP/IP) or is there something else?

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internet_protocol_suite

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/OSI_model

- - Protocols:

- - SSH (why pi / to enable networked/remote collaboration)

- https://www.raspberrypi.com/documentation/computers/remote-access.html#ssh

- - Default Password Access

- - Setting up SSH keys per User

- - TMUX ?

- - HTTP

- - Default set up on a pi?

- - Setting up a server with Nginx

- IP Addresses mapped to DNS / A Records / Tuxic

- Hand over to Syster Server Chapter? VPNs, Tinc, Reverse Proxy servers / routing traffic?

- ↑ Link to intro? to a part explaining writing on wiki4print?

- ↑ See (need edit the citation): https://areyoubeingserved.constantvzw.org/

- ↑ See (need edit the citation): https://aprja.net/article/view/140450, and there are more discussion about Systerserver in Chapter 3

- ↑ p.4 (need edit the citation) https://psaroskalazines.gr/pdf/ATNOFS-screen.pdf

- ↑ See the call and the list of participating collectivities here: https://circex.org/en/news/8m

- ↑ See: https://darc.au.dk/blog/nyhed/artikel/toward-a-minor-tech-workshop-publication

- ↑ See: https://ctp.cc.au.dk/

- ↑ In 2022, the CTP project invited Systerserver to deliver a workshop titled "Hello Terminal", intended as a hands-on introduction to system administration. However, the remote access port was blocked, preventing anyone without a university account and Virtual Private Network (VPN) from logging in, significantly restricting participation and what people can do with the servers. If we want to understand infrastructure, fundamental questions such as what is a server and how to configure one naturally arise. Approaching these requires access to a computer terminal and specific user permissions for configuration or installation—areas traditionally managed by IT departments. Most universities, however, provide only "clean" server spaces (preconfigured server environments) or rely on big tech software and software that offer secure, easy-to-maintain solutions, limiting hands-on exposure to the underlying setup and infrastructure. This issue, among others, will be explored further in Chapter 3

- ↑ See https://www.centreforthestudyof.net/?p=7032

- ↑ https://datasheets.raspberrypi.com/rpi4/raspberry-pi-4-datasheet.pdf

- ↑ https://permacomputing.net/SBC_power_consumption/

- ↑ https://permacomputing.net/single-board_computer/

- ↑ https://libre.computer/

- ↑ https://microbit.org/about/mission/

- ↑ https://www.raspberrypi.org/about/

- ↑ Burrington, Ingrid. Networks of New York: An Illustrated Field Guide to Urban Internet Infrastructure. Melville House, 2016.

- ↑ A meanwhile use is a type of tenancy, whereby developers/the council allow another company or individuals rent a space for a variable amount of time before that site is redeveloped. This means that the buildings may not be actively maintained/improved due to the possibility of immenent redevelopment. The length of tenancy is also very varied, and can be indefinate until the property owners notify the tenants. In the case of the site we are describing, it is currently in an disused office block which is due to be demolished. The sites tenants have been given notice that the property owners have permission to develop the site, but when that will happen is still unclear and could be as soon as one year, or several years away.

- ↑ https://www.artmonthly.co.uk/magazine/site/article/high-streets-for-all-by-matthew-noel-tod-may-2021

Writing link: https://pad.riseup.net/p/PlatformInfrastructure-keep

index.php?title=Category:ServPub