No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

{{ :Chapter_2b:_Server_Issues:_Networked_Infrastructure }} | |||

| Line 73: | Line 73: | ||

{{ :Chapter_4a:_Computational_Publishing }} | |||

| Line 81: | Line 81: | ||

{{ :Chapter_4b:_Public:_FLOSS_Design}} | |||

| Line 89: | Line 89: | ||

{{ :Chapter_3:_Praxis_Doubling}} | |||

| Line 97: | Line 97: | ||

{{ :Chapter 4c: Publishing & Distribution }} | |||

| Line 105: | Line 105: | ||

{{ :Chapter_5b:_Distribution }} | |||

Revision as of 12:37, 19 September 2025

ServPub

Author: [Author Name]

Publisher: [Publisher Name]

ISBN: [ISBN Number]

Publication Date: [Publication Date]

Edition: [Edition Number, if applicable]

Foreword

Lorem ipsum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed non risus. Suspendisse lectus tortor, dignissim sit amet, adipiscing nec, ultricies sed, dolor. Cras elementum ultrices diam. Maecenas ligula massa, varius a, semper congue, euismod non, mi. Proin porttitor, orci nec nonummy molestie, enim est eleifend mi, non fermentum diam nisl sit amet erat. Duis semper. Duis arcu massa, scelerisque vitae, consequat in, pretium a, enim. Pellentesque congue.

Praesent vitae arcu tempor neque lacinia pretium. Nulla facilisi. Aenean nec eros. Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Suspendisse sollicitudin velit sed leo. Ut pharetra augue nec augue.

Fusce euismod consequat ante. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer adipiscing elit. Pellentesque sed dolor. Aliquam congue fermentum nisl. Mauris accumsan nulla vel diam.

Contents

"Activist infrastructures are where the messy, grinding, generally invisible labor of 'doing feminism' takes place." Cait McKinney in Information Activism - A Queer History of Lesbian Media, 2020[1]

Being part of internets

Systerserver, a feminist server project of almost two decades,[2] has supported the Servpub project with their network infrastructure. The feminists involved in this project have configured their own infrastructure of two physical servers in the data room of [mur.at], an art association in Graz, Austria, which hosts a wide variety of art and cultural initiatives. The physical servers found this shelter through the networking of activists and artists during Eclectic Tech Carnival (/ETC), a self organized skill sharing gathering. Donna Meltzer and Gaba from Systerserver went to Graz to upgrade the servers' hardware in 2019. The first machine, installed and configured in 2005, is called Jean and was refurbished by ooooo in 2023 during their stay in Graz for the Traversal Network of Feminist Servers[3]. The gathering was hosted by ESC, a local media art gallery in Graz, which is affiliated with [mur.at].

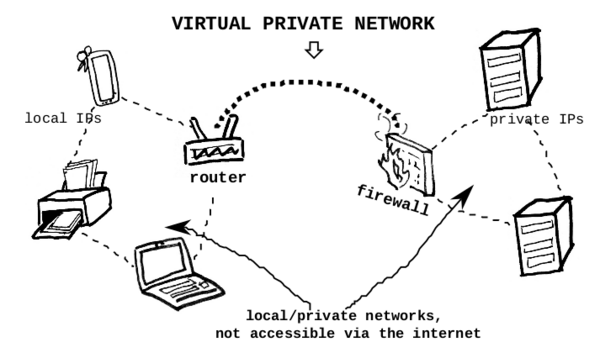

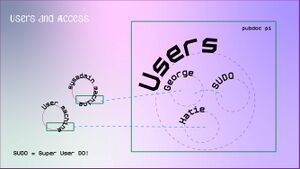

Both servers are running on Debian, which is a Linux based operating system and host several tools for community communications and organising,[4] among which Tinc, a virtual private network (VPN) software. The VPN is the most recent addition, facilitating the desire for self hosted servers by our peers, from their homes, studios and spaces that cannot afford a stable digital address.[5] Those server projects interweave into a feminist networking, an affective, socio-technical infrastructure, enabling the emergence of more trans-feminist groups and collectives like actinomy (Bremen), leverburns (Amsterdam), caladona (Barcelona), brknhs (Berlin) to host their own servers in their own spaces rather than in data centers, and be reachable through the public internet.

Tinc was chosen as VPN software, mimicking of what Systerserver learnt during their participation in the project A Traversal Network of Feminist Servers (ATNOFS), encountering the mobile server Rosa.[6] Rosa is a server connected to the Internet via a VPN, hosted by the Rotterdam based space Varia, which was inspired by another relevant network infrastructure setup, that of the Rotterdam based institute XPUB.[7] Constant association in Brussels and Hackers and Designers collective in Amsterdam, have also experimented with similar VPN based servers.[8] The people, groups and spaces involved in these servers experiments often overlap, which is also due to the physical proximity of the projects (Rotterdam, Brussels, Amsterdam).

Being a server

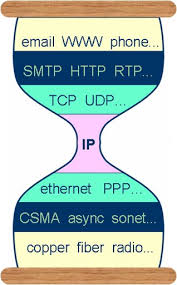

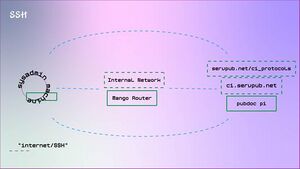

A VPN software creates virtual private networks, connecting computers and devices that are not sharing the same physical location. In contrast to the internet, the network between these devices is concealed, thus called private, as it only exists between the trusted devices that are added to this network. A VPN can also facilitate a public entry point to these private network connected devices, making them reachable in the public Internet and thus allowing them to become servers. When devices are connected to the Internet, they are assigned a numeric notation, called Internet Protocol (IP) address. A home or office router, is assigned a public IP by its Internet Service Provider (ISP), which changes periodically, so called dynamic. The ISP distributes these IP address from a limited pool of addresses, which expire and trigger an IP address change, so called a lease time, allowing the ISP to provide Internet connection to many more locations than the amount of its IP pool. ISP do this to manage their available addresses more efficiently and for minor security benefits.[9] All devices within a home or office, are assigned what is called a local IP from the router, which by its default settings it allows Internet traffic in one way, e.g as websites' content (response), and doesn't allow the devices to send traffic outside the home or the office but only requests. However, within a VPN network, the devices are assigned a private IP by the VPN software, and are able to receive and send traffic outside their physical location.

Visiting a device over the Internet, by remembering their IP, would be a challenging if not impossible thing to do. Thus the need for domain names such as www.servpub.net, which are mapped to an IP address. So when this domain name is visited, the browser can present the content of e.g a website hosted on that device. Retaining this IP the same becomes important for mapping it to a domain name, therefore it's also known as fixed or static IP. The translation of IP to domain names and back, happens with Domain Name Servers or DNS.[10]

So if a request is made to wiki4print.servpub.net, the request will first reach Jean, whose IP is mapped to that domain, because Jean is the only computer with a public and static IP address within this private network. On Jean, a web engine configuration software forwards the request to the private IP of the device, which it actually hosts ServPub project's wiki. The request is thus rerouted internally, meaning inside the concealed virtual private network, to the specific device, which hosts the wiki4print website. This forwarding request from the public IP to the private, is called a proxy request, and the ability of the device to send out data back through the public node, thus being a server, is enabled via a reverse proxy.

Systerserver has configured three of these private networks with Tinc, to reach home based servers which have no public and static IP address: internes, alliances and systerserver.[11] The network named systerserver was the first installation and configuration of Tinc for Systerserver's infrastructure. It was initiated for the publishing infrastructure of the ServPub project. The systerserver network allows the raspberry-pies, which host the wiki4print and the ServPub website to be accessible in the internet via Systerserver's public node and machine Jean. Arriving to the first technical attempt of configuring the network systerserver required trust building between Systerserver peers and No Names, which commenced through the participation of Winnie Soon in one of Systerserver's week-long event and workshop in Barcelona back in 2023, during which Systerserver installed PeerTube for and with caladona women's space. Such collective and grassroots organising based events, i messy, campy, the base for bonding and solidarity, which builds upon the invisible labour of doing feminism (McKinney 2020). By understanding together computing, configuring machines, conversing about big tech and its sexism, racial, class and gender discrimination, the people gathered around these events, nourish a resistance through body and identity politics, which transgress labor exchanges on economic value alone.

Looking at the initial architecture of the Internet as a communication medium where a node can reach any other node, and the importance of a node to be authenticated by their address as a unique identifier, the current landscape has transformed to something quite different. Since the end of the 90s the development of the IPv6 protocol was conceived [12] for mitigating the depletion of IPv4 addresses, by enabling larger addresses restoring the initial numeric notation, which hasn't been long enough to cover the massive proliferation of devices. IPv6 was also conceived with embedded security within the IP packet itself. IPv4 required an external configuration of encryption and brought about the development of the encryption protocol IPSec around the mid-1990s, which provided an end-to-end security wrapped around the IP layer, authenticating and encrypting each IP packet. While IPSec ensured encryption for IPv4, it requires extra software installation and configuration steps, but it was incorporated as a core component of IPv6.[13] Therefore, while internet communications over the web, provide encryption with the secure HTTPS certificate,[14] other internet connections, e.g files syncing over two machines, require extra encryption configurations and/or VPN tunnels.

The use of secure certificates encrypts the traffic over the connection cable and waves, but once the data arrive at their destination server are not encrypted. Thus unencrypted data can be cached and served by intermediaries, which are located closer to users' internet access. E.g when we request again the same website, the content may be served by what is known as Content Distribution Networks (CDNs), rather than the requested server. CDN providers deliver much of today’s Internet content by caching it on servers distributed around the world. By serving data from servers that are geographically close to users, they greatly reduce the impact of physical distance between the user’s Internet access point and the origin server, which in turn speeds up load times. However this centralisation of content, which has been made possible due to digital storage and computing becoming inexpensive since the 2010's, raises several user‑rights concerns despite their performance benefits. Because they terminate secure certificates and have access to unencrypted data, they add an extra point where user data can be inspected, monitored, breached, and their central position also enables large‑scale blocking, filtering and surveillance capitalism that can affect e.g the exercise of erasure, especially when data is moved across borders.[15]

The lower motivation for business to offer and maintain both IPv4 and IPv6 network stack, as other technologies such as address-sharing[16] and CDNs have fixed the issue of handling the scarcity of IP addresses,[17] have contributed to a decreased pace in the advancement of IPv6 rollout to all devices. Considering the potential impact of IPv6 where data remain encrypted through out all connections, one may argue whether the embedded encryption within the IPv6 packet for each device on the Internet, it is a civil right to security and privacy that the industry and states' surveillance would rather avoid. At the same time, ISPs can charge higher prices for a reduced number of IPv4 addresses and in some cases, legacy IP blocks of addresses can even be sold in the grey market, because those blocks were not regulated by any regional internet registry system since they were allocated before those registries came to existence.[18]

It is interesting to think of a VPN as a way to render our data unreadable by non-consensual monitoring eyes. In the case of ServPub ambulant server, as a resistance to a university rigid network configuration, besides the wider accessibility and mobility of the server, the content traveling through private networks enforces data encryption and authentication by the VPN software design, and thus becoming unreadable, untraceable and fearless to censorship. What also becomes untraceable is the geolocation of the servers within the private network.

During the translation of Tunnel Up/ Tunnel Down Zine in Chinese,[19] the artist and translator Biyi Wen, referred to the art research project "A Tour of Suspended Handshakes". In this project, artist Cheng Guo physically visits some nodes of China’s Great Firewall. Using network diagnostic tools, the artist identified the geolocations mapped to IP addresses of these critical gateways,[20], which filter data from outside China, based on data published by other researchers. These gateways' function of filtering is what constitutes them as firewalls. At times, the geolocations visited by the artist corresponded to scientific and academic centres, posing like plausible sites for gateway infrastructure. Other times, they lead to desolate locations with no apparent technological presence. While Guo acknowledges that some gateways may be hidden or disguised - for example, antennas camouflaged as lamp posts - the primary reason for these discrepancies lies in the redistribution of IP addresses, due to their resale. These factors make it difficult to pinpoint exact geographical locations. Moreover mapping activities have been illegal in mainland China since 2002, and coordinates remain hidden from the public.[21]

In the case of the Great Firewall, the combination of IP redistribution and encrypted coordinates obscures the true geolocations of its gateways, rendering the firewall a nebulous and elusive system. For the mobile (ambulant) servers, their exact geolocation remains obscure too, because they are concealed within the virtual private network -beyond the main public-facing nodes such as Jean-. However, unlike the Great Firewall, the concealment of the ambulant servers is not enforced through a top-down governmental control. The desire to be addressable from home based infrastructures through a trusted network-sharing of tunnels and reverse proxies through community-run servers,[22] brings about the potential to circumvent censorship, surveillance, and centralisation by commercial CDNs, states or other institutional firewalls, rendering this imposed scarcity of IPv4 into a solidarity action.

While writing this chapter, the project of Alison Macrina on Library Freedom Project and Tor Browser was referred to and it is worth mentioning as a concrete, real‑world activist case, reinforcing the "messy, grinding labor of doing feminism". Alison's Library Freedom Project exemplifies this by turning libraries into practical privacy infrastructure sites, teaching surveillance resistance via Tor relays, and anonymise traffic and reclaim data sovereignty, much like Systerserver's VPNs and reverse proxies resist centralised control.

Digital literacies

Being part of the internet, or internets,[23] creating and maintaining our own networked infrastructures involves an understanding of the technicalities and politics of IP addresses, routers and gateways, and the economy of IP scarcity and institutional and corporate control. One way of addressing the politics and economies of network infrastructures and of how to relate to technology is by 'following the data'. Data is not just an informational unit or a technicality, it is how we as trans*feminists relate to computers, both on a supra- or infra-individual level but also as something that can be incredibly personal and intimate. We need to keep asking 'where is the data?'. We need to develop technical awareness and accountability in how we participate and how we are complicit in the infrastructures in which our data is created, stored, sold and analyzed. In 'following the data', we become more engaged and cultivate our sensibilities around data and networked infrastructure politics.[24]

By making digital infrastructures and technicalities visible with the aid of drawings, diagrams, manuals, metaphors, performances and gatherings, Systerserver traverses technical knowledge with an aim to de-cloud (Hilfling Ritasdatter, Gansing, 2024) data and redistribute networks of machines and humans/species. Systerserver therefore, becomes a space to exchange knowledge, whose sysadmins maintain and care together in non-hierarchical and non-meritocratic ways, which the sysadmins refer to as 'feminist pedagogies'. These pedagogies cultivate a socio-technical learning by accepting divers life experiences, recognising that knowledge is socially constructed, questioning digital hegemonies, and welcoming situated experiences from the places where we physically meet for the trans-feminist gatherings of Eclectic Tech Carnival (/ETC), TransHackFeminist Convergence (THF), or other. These meetings or rather offline and online entanglements are encouraging to Do-It-Together, give time and space to study and collectively write documentation. They collectivize moments of choosing our dependencies, while feeling trusted in a safe(r) place to learn about technicalities. They challenge our bodies-machines relations.

How can we imagine a virtual private server, in a material world? An intervention by ooooo and others during the rehabilitation of an eco-industrial colony in the mountains near Barcelona, Calafou, a room was transformed into a physical public interface for the practices around the feminist server: anarchaserver.org[25] Open for visitors, it was used during system administrative work sessions, and for gatherings, sonic improvisations and radio. The door, window, ceilings and multi-levels were analogous to the functionalities of a server’s hardware-software counterparts (ports, encryption, including a repository, and even a firewall). It also had a bed, where somebody could sleep, rest and reside in analogy with the Living Data container, which hosts ALEXANDRIA for wiki documenting and ZOIA HORN for multi-site blogging. It was also activated during THF Convergence, an event of intersectional feminists, queer and trans people of all genders to better understand, use and ultimately develop free and liberating technologies for social dissent.

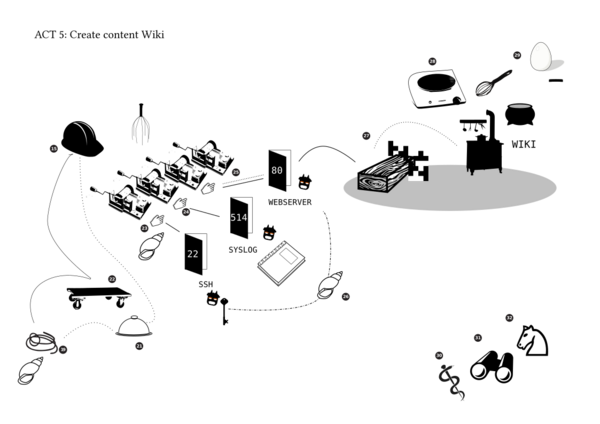

With the question How to collectively embody a server? ooooo made another performative event during The Feminist Server Summit, 12–15 December 2013[26], organized by Constant association of media arts in Brussels. In Home is a server fourteen people were invited to choose a prop representing the different hardware parts of a computer (CPU, RAM, watchdogs, ports, kernels, hard drives). By reading a script together, they followed the data flow while installing a server, install a wiki and publish a recipe for pancakes which they bake and eat together.

Are we vulnerable, safe and do we need to encrypt? In different exercises combining dance notations, crypto techniques and careful somatic tactics participants embody issues of security, privacy, safety and surveillance. Cryptodance was a performative event which was developed in August 2016 during the preparations for THF 2016!, by a small international constellation of choreographers, hackers and dancers. [27]

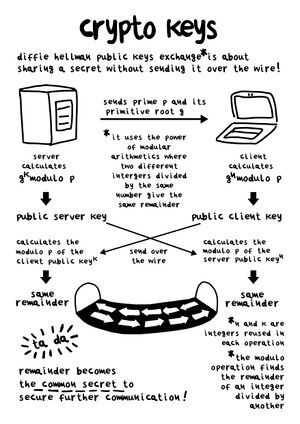

Crypto Keys is a drawing illustrating the mathematical formulas used in the Diffie Hellman algorithm for encrypting data over the Internet without the need to exchange the password or secret key.

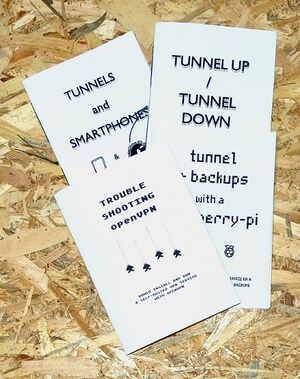

VPN introduction zines is a series of manuals about private virtual networks illustrating with drawings technical concepts of firewalls, authentication and encryption over the Internet, how we can install a VPN with a single board computer, on mobile phones, and when to chose for a VPN over a proxy.

What is feminist federation? Another example of making analogies and tangible translations, it the performative event Humming Birds. With the aid of choreographies, sociometric exercises and voicing techniques, participants explore the social network Fediverse and get introduced in a technical understanding of its protocol ActivityPub, which is a standard for publishing content in a decentralized social networking.[28]

A feminist networking

"Technologies are about relations with things we would like to relate to, but also things we don't want to be related to" Femke Snelting in Forms of Ongoingness, 2018[29]

A feminist server goes beyond a technically facilitated node in the network, and becomes an (online) space in understanding digital infrastructures and resist hegemonies. It can be entered "as an inhabitant, to which we make contributions, nurture a safe space and a place for expression and experimentation, a place for taking a role in hacking heteronormativity and patriarchy."[30] A feminist server is a place where we as trans*feminists can share with intersectional, queer and feminist communities, a place where our data and the contents of our websites are hosted, where we are chatting, storing stories and imaginaries, and accessing the tools we need to get organized (mailing lists, calendars, etherpads). Serving, and becoming a server is not just a neutral relation between two or more computers.[31] It is tied to politics of protocols, of infrastructure capacity and power, responsibilities, dependencies, invisible labour, knowledge, and control. A feminist server is a space where we learn how a collective emancipation is possible from the techno-fascist platforms and content service providers. As feminist servers, we refuse to be served in networks that increase our dependencies on cis male dominated and extractivist technologies of big tech. Having a place or 'a room of one's own' on the internet is therefore important, referencing historic feminist struggles for agency, and safe/r off- and online spaces for uninterrupted time together to imagine technological praxis otherwise.

Furthermore, the metaphor of one's own room[32] highlights the ways in which bodies need to be accommodated in the practices of feminist servers and social networking. These bodies incorporate our data bodies[33] but also the ways in which we show up in gatherings and places outside the digital networks. Self-organised gatherings such as the Eclectic Tech Carnival (/ETC)[34] or the TransHackFeminist convergence (THF),[35] and feminist hacklabs such as marialab, fluid.space, mz balathazar’s laboratory, t_cyberhol, as well as (art) residencies or other larger gatherings (Global Gathering, Privacycamp, OFFDEM, CCC) have been crucially nurturing and fueling the desires for our own servers. These gatherings address the need to share ways of doing, tools and strategies to overcome and overthrow the monocultural, centralised oligopolic technologies of surveillance and control, to resist the matrix of domination. These are moments where social networking can materialize into feminist servers and affective infrastructures.[36]

Social networking, which shapes affective infrastructures, can be in that sense laborious, an act of care, of wielding solidarities, of sharing and of growing alliances, recognizing our precarities, identities and collective oppressions. It is a community practice, a way of staying connected and connecting anew, of looking for and cherishing those critical connections[37] which are always already more than technical. Those critical connections can become a feminist networking, a situated techno-political practice that engages us in more-than-human relations with hardware, wetware and software.

In terms of feminist servers, the server thus becomes a 'connected room' or even 'infrastructures of one's own', characterized by the tension between the need for self-determination and the promiscuous and contagious practices of networking and making contact with others. These practices inherently surpass strong notions of the individual 'self', facilitating instead a collective and heterogeneous search for empowerment, and partake in creating the conditions for networked subjectivities and solidarities. They transform to a connected room,[38] a network of one's own, with allies as co-dependencies, attributing each other(s), interacting as radical references[39] to evade hierarchies of cultural capital, and instead sustain collective efforts of resistance against capitalistic logics of knowledge production. When one is talking about the internet and its potential for feminist networking, one needs to move away from thinking of it as something 'given' that we might 'use'. One needs to shift away from the cloudy image of cyberspace serving the extension and intensification of capital, governance and data power.[40]

ServPub, being a publishing platform for collaboration, learning digital infrastructuring while doing it, and being part of Systerserver's internet and networking, is moving toward feminist forms of affective infrastructures.

- ↑ Cait McKinney, Information Activism, A Queer History of Lesbian Media Technologies (Duke University Press, 2020)

- ↑ For more information on the genealogy of Systerserver see Wessalowski, N. & Karagianni, M. “From Feminist Servers to Feminist Federation.” A Peer-Reviewed Journal About 12, no. 1 (September 7, 2023): 192–208. https://doi.org/10.7146/aprja.v12i1.140450.

- ↑ Chapter 2: Traveling server space: Why does it matter?, “A Traversal Network of Feminist Servers” 2022.

- ↑ Systerserver hosts a GitLab instance as code repository, Peertube for video and streaming, Mailman for mailinglists, Nextcloud for data storage and collective organisation, Mastodon providing a microblogging social networking platform, Tinc VPN, and relevant code based projects and websites. For links to each service, visit https://systerserver.net/

- ↑ Configuring a server, requires what is known as a fixed IP address, which is a numeric notation, signaling the location of the server. This IP address can be mapped to a domain name, which in turn can be traceable in the Internet when visiting said domain name in a browser.

- ↑ Rosa is rasperry-pi server using, varia.hub to be reachable on the internet. varia hub is what in varia they cal a jumphole, a poetic description for the VPN + reversey proxy through their servers. Varia is a space for developing collective approaches to everyday technology, work with free software, organise events and collaborate in different constellations. https://varia.zone/en/

- ↑ XPUB is the Master of Arts in Fine Art and Design: Experimental Publishing of the Piet Zwart Institute in Rotterdam. XPUB focuses on the acts of making things public and creating publics in the age of post-digital networks. The VPN software Tinc and reverse proxy is inspired by their HUB project, which enabled the Institute to form an experimental server space for their students which could access the server from outside the Institute, passing institutional firewalls securely and let devices roam. See Docs:03_VPN_with_Tinc

- ↑ Also Mara Karagianni, Michael Murtague and Wendy Van Wynsberghe, were commissioned by Constant for writing a zine manual on Tinc and reverse proxies: Making A Private server Ambulant, https://psaroskalazines.gr/pdf/rosa_beta_25_jan_23.pdf The beta version of the zine was revisioned and updated by vo ezn, also part of Systerserver. She deployed it in the digital infrastructure of Hackers and Designers.

- ↑ IP address lease times provide security benefits such as preventing persistent unauthorized use, reduce risks such as IP spoofing and theft, allow rapid response to misuse by removing compromised devices from the network.

- ↑ A fun guide to what is a DNS, and computer networking in general, it's the zine Networking! Ack! by Julia Evans, 2017, available at https://jvns.ca/networking-zine.pdf

- ↑ The internes is for Systerserver's machines located in [mur.at] to reach a machine in Antwerp, which is making periodic backups of the servers Jean and Adele. The network alliances is for facilitating a few of home-based server initiatives within Systerserver's extensive community, such as the etherpad services hosted on the server leverburns which Systerserver uses for technical documentation during server maintenance sessions, or for other allied communities such as caladona and brknhs that want to serve video content without having to commit to the expenses of acquiring a public and static IP address.

- ↑ The first publication of the IPv6 protocol in a Request for Comments was in December 1998, accessed on September 20th, 2025, https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc2460.txt

- ↑ Besides IPv6 protocol being a secure protocol with extra authentication and privacy, it also has support for unicast, multicast, anycast. See more at Internetworking with TCP/IP, Vol. 2 by Douglas E. Comer and David L. Stevens, published by Englewood Cliffs, N.J. : Prentice Hall, 1998, accessed on September 20th, 2025, https://archive.org/details/internetworking000come

- ↑ While HTTPS is a way to secure traffic over the internet, it is distinguished from IPSec in that IPSec secures all data traffic within an IP network, suitable for site-to-site connectivity. HTTPS, the secure version of HTTP, using TLS certificates, secures individual web sessions. The authentication with a TLS certificate relies on the organisation or company's name ownership of the certificate, and not on the integrity of the server's IP address. This fact enables CDNs to cache content and serve in place of the origin server, which contributes to the centralisation of content distribution over the web. https://gcore.com/learning/tls-on-cdn More about how TLS works https://www.bacloud.com/en/blog/190/ssl-for-ip-lets-encrypt-now-supports-tlsorssl-certificates-for-ip-addresses.html

- ↑ E.g data harvesting and extensive users profiling without consent violates the EU law General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), https://wideangle.co/blog/content-delivery-network-cdn-and-gdpr

- ↑ See for example routing via Network Address Translation (NAT), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Network_address_translation

- ↑ Geoff Huston, The IPv6 transition, 2024, accessed on September 20th, 2025 at https://blog.apnic.net/2024/10/22/the-ipv6-transition/

- ↑ The African continent registry AFRINIC have been under scrutiny due to organizational and legal problems. In 2019, 4.1 million IPv4 addresses part of unused legacy IP blocks, were sold on the grey market. Accessed online on 25 July 2025 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AFRINIC.

- ↑ Tunnel Up/ Tunnel Down, Mara Karagianni, a self-published zine about what is a VPN and its various uses and technologies, 2019, https://psaroskalazines.gr/pdf/fanzine-VPN-screen-en.pdf.

- ↑ A gateway is a network device that acts as an entry and exit point between two different networks, translating and routing traffic so they can communicate. While a home or office router, mainly forwards packets between networks that use typically IP, a gateway connects different kinds of networks and can translate between differnet protocols or data formats, and often operating across multiple OSI layers.

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Restrictions_on_geographic_data_in_China

- ↑ Dynamic DNS is another option for when your ISP changes your home network's IP address.It is a commercial service that allows you also to use a fixed address for your home network. You can often set up DDNS on your router. Self-hosted website or online resource will be redirected over commercial nodes maintained by companies; companies which are often known for data-exploitation, acts of censorship and compliance with states agencies in cases of political prosecution.

- ↑ Networks with an Attitude was a worksession to think of the future of Internet, organised by Constant from 7 to 13 April 2019 at various locations in Antwerp.The internet is dead, long live the internets! https://constantvzw.org/sponge/s/?u=https://www.constantvzw.org/site/-Networks-with-an-Attitude-.html

- ↑ Gray, Jonathan, Carolin Gerlitz, and Liliana Bounegru. “Data Infrastructure Literacy.” Big Data & Society 5, no. 2 (July 1, 2018) https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2053951718786316

- ↑ The documentation of this process https://zoiahorn.anarchaserver.org/physical-process/ is hosted on the anarchaserver. Anarchaserver is an allied feminist server which contributes to the maintenance of autonomous infrastructure on the Internet for feminists projects and was setup in Calafou, Spain.

- ↑ The fourteenth edition of the meeting days Verbindingen/Jonctions organized by constant vzw in December 2013 was dedicated to a Feminist review of mesh, cloud, autonomous, and DIY servers. https://areyoubeingserved.constantvzw.org/Summit.xhtml

- ↑ Goldjian and bolwerK started plotting the Cryptodance project during a Ministry of Hacking (hosted by esc in Graz, Austria), where they formed a joint(ad)venture of the Department of Waves and Shadow and the Department of Care and Wonder.Cryptodance - THF 2016

- ↑ Nate Wessalowski and xm developed it during 360 degrees of proximities for the cyborg collective of Caladona, a women center in Barcelona with whom they together installed peertube on a self-hosted server. ActivityPub provides a client-to-server API for creating and modifying content, as well as a federated server-to-server protocol for delivering notifications and content to other servers.

- ↑ Sollfrank, C."Forms of Ongoingness. Interview with Femke Snelting and spideralex". House for Electronic Arts (HeK), Basel. (September18, 2018) https://creatingcommons.zhdk.ch/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Transcript-Femkespider.pdf

- ↑ spideralex in Sollfrank, C."Forms of Ongoingness. Interview with Femke Snelting and spideralex". House for Electronic Arts (HeK), Basel. (September18, 2018) https://creatingcommons.zhdk.ch/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Transcript-Femkespider.pdf

- ↑ Gargaglione, E. “Hacking Maintenance With Care Reflections on the Self-administered Survival of Digital Solidarity Networks". Roots§Routes. (May 14, 2023). https://www.roots-routes.org/hacking-maintenance-with-care-reflections-on-the-self-administered-survival-of-digital-solidarity-networks-by-erica-gargaglione/ [client/server nor user/developper]

- ↑ Networks Of One’s Own is a periodic para-nodal publication by varia. September 2019. https://networksofonesown.varia.zone/

- ↑ Association for Progressive Communications.: Peña, P and Varon,J. “Consent to Our Data Bodies: Lessons From Feminist Theories to Enforce Data Protection,” oding Rights (March 25, 2019). https://www.apc.org/en/pubs/consent-our-data-bodies-lessons-feminist-theories-enforce-data-protection

- ↑ The Eclectic Tech Carnival (/ETC) is a potent gathering of feminists who critically explore and develop everyday skills and information technologies in the context of free software and open hardware. /ETC chews on the roots of control and domination, disrupts patriarchal societies and imagines better alternatives. https://monoskop.org/Eclectic_Tech_Carnival

- ↑ https://alexandria.anarchaserver.org/index.php/Main_Page#TransHackFeminist_Convergence

- ↑ Wessalowski, N. & Karagianni, M. “From Feminist Servers to Feminist Federation.” A Peer-Reviewed Journal About 12, no. 1 (September 7, 2023): 192–208. https://doi.org/10.7146/aprja.v12i1.140450

- ↑ Following a quote from Grace Lee Hoggs on connectedness and activism which puts 'critical connections' over 'critical mass' after an idea by Margaret Wheatly. Boggs, G., Kurashige, S. The Next American Revolution: Sustainable Activism for the Twenty-First Century. Univ of California Press, 2012. p.50)

- ↑ See also spideralex, referencing Remedios Zafra's book "A Connected Room of One’s Own" https://www.remedioszafra.net/aconnectedroom.html in Sollfrank, C."Forms of Ongoingness. Interview with Femke Snelting and spideralex". House for Electronic Arts (HeK), Basel. (September18, 2018) https://creatingcommons.zhdk.ch/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Transcript-Femkespider.pdf

- ↑ Term introduced in this book by ooooo, which got picked up an lead to an in depth article on the subject in Chapter_5b:_Distribution

- ↑ Metahaven, Daniel van der Velden, and Vinca Kruk. 2012. ‘Captives of the Cloud: Part I’. E-Flux 37.

stepped back

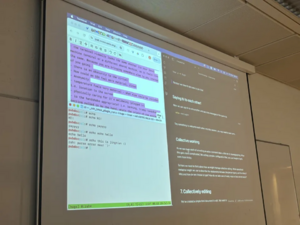

Designing with wiki4print

Creative Crowd's Wiki-to-print is a web-to-print collective publishing environment. Content written into the wiki is used to lay out and design a PDF in the browser using web technologies, it is based on MediaWiki software[4], Paged Media CSS techniques[5] and the JavaScript library Paged.js[6][7]. wiki-to-print/wiki-to-pdf/wiki2print is not a standalone tool and we trace some of these histories within this chapter, it is part of "a continuum of projects that see software as something to learn from, adapt, transform and change"[8].2+to=4/for

to from Creative Crowd's wiki-to-print[1]

2 from Hackers and Designers wiki2print [2]

4 as it is what the wiki is for

for as it is the fourth iteration since TITiPI's wiki2pdf[3]

"Using wiki-to-print allows us to work shoulder-to-shoulder as collaborative writers, editors, designers, developers, in a non-linear publishing workflow where design and content unfolds at the same time, allowing the one to shape the other." [9] - CC

In-grid wiki-to-print(ing)

The design work for the book was done primarily by members of In-grid. When the Servpub project began in 2023, none of us were particularly familiar with the technical setup of wikis or computational publishing with Free Libre and Open Source Software (FLOSS). As design practitioners, our reliance on the Adobe suite that has a toolset tailored for print and digital publishing had to be reconsidered. Our encounter with web-to-print practices has been thanks to Creative Crowds (CC) and the use of wiki-to-print, which operates on Servpub as wiki4print. In-grid has been on a journey of working with the constraints of open-source design, namely learning how to bridge the practices of web development into the domain of design for print, and working within the ecologies of FLOSS.

As Creative Crowd said to us, it is quite radical to have wiki-to-print as our first step into the world of web-to-print and working with wikis. During internal conversations with the ServPub book designer, Johanna de Verdier, she mentioned frustrations while learning to use wiki-to-print such as being "unable to streamline design the same way as you would have been able to with the Adobe suite" and the "lack of being able to mock things up visually" in the same way. Working within an ecosystem of design software that is dominated by Adobe, the designer is a user of a suite of tools that provide graphical user interfaces to do visual design in prescriptive ways. It is from this context that the idea of design software as a tool can start to be questioned.

During a conversation with CC, they expressed that it's difficult to talk about wiki-to-print in a general way, as it was made for particular situations, both technical and social. They explained that calling wiki-to-print a tool flattens the socio-technical practices of wiki-to-print. The social practice of wiki-to-print(ing) has thus become a way for In-grid to think about the ongoing relational aspects that emerged within the Servpub project. This encompasses the productive frictions between FLOSS Design and out of the box design software (like Adobe)."Calling wiki-to-print a practice indicates that it's more than a production tool" - CC

Within this chapter we present an interview In-grid had with CC. Through the interview, we aim to share how this web-to-print infrastructure, social practice and frictions within processes shapes and situates what wiki4print is in action.

CC Interview

31st Oct 2025 (Using signal for video call)

Could you introduce yourself a little bit?

Simon My name is Simon Browne. I live in Rotterdam in the Netherlands, but I'm not from the Netherlands. I came here probably about eight years ago, and I studied at XPub, which is the Experimental Publishing Master of the Piet Zwart Institute. Since then, I've gone on to become really involved in a lot of collective publishing work. So at the moment I'm part of Varia in Rotterdam and OSP or Open Source Publishing in Brussels. Then also with Manetta, we both do this thing that we call CC, Creative Crowds.

Manetta

My name is Manetta, Manetta Berends. I live in Rotterdam as well, for 12 years already. I'm from the Netherlands and came to Rotterdam to study in this same master course that was called Media Design at the time, now called Experimental Publishing, which is also the place that I currently am involved at as a tutor. I’m from a background in more traditional graphic design during my Bachelor studies, I have grown into a practice that is very collective, that is about making tools or practicing with making tools, or practice and tools. We will talk about that more throughout the interview. That meant that my practice shifted a lot from being someone who would work in commissions towards someone who is also organising events, being involved in a community of practice, doing some writing here and there, making some things that you could, I guess, called tools. Being involved in practice in different ways, with a specific focus on collective publishing environments.

Manetta

It's very hard to start talking about the history of that practice of working with wikis, publishing and making publishing environments out of them.

I think there are multiple lines that can be traced. One that has been important for myself has been the making of a book called Volumetric Regimes, published by the Data Browser series of the Open Humanities Press. That was a work closely made with the editors of the book, Femke Snelting and Jara Rocha, who proposed to work with the wiki because they had the interest, and also published a wiki version of the book online. Femke had been very, very involved in working with OSP, with whom she had made another book in the context of Constant's project called Diversions, and another book before that, also in the context of Constant, called Mondothèque. Building upon that practice, seeing what has happened around these particular projects, that has been very informative and inspiring to think about how very practically an editorial process could be shaped.

Simon

I don't have much more to add. I mean, I think the fear for me about giving a historical account to Wiki to print is that somewhere in the world there's somebody who's working with a Wiki and making PDFs. And we're going to leave their name out. We're not going to mention them. So I think there's definitely a culture of people using Wikis to make PDFs within the network that we're part of, and we can talk to that a little bit about, so Manetta already mentioned the Mondothèque project and the Diversions project, which were both using a wiki to write. With Diversions, it really questions the ownership or authorship of material in a wiki, because when you're writing in a wiki, there is this notion that you're collaboratively editing things and there's a way that you can see lots of different versions of texts. But I think for me personally, I first came across Wiki to Print when working on a commission that came through Varia, that Manetta and I were both working on, for a Peer-Reviewed Newspaper About: Minor Tech. So Manneta has been using it before and she introduced it to me and I was like, wow, okay, so you can use a wiki to make a whole bunch of different publications. What was exciting about it was really the idea of versions of publications that can come from the one wiki. But I have to say, in my own experience, I haven't really explored that so much. It's really just been about producing one version of one publication.

Manetta

Maybe one more line to trace, because I think it may not be a very direct sort of historical line, if we can call it that, but more like an indirect, very important one is that we both have been involved in wiki writing quite a bit. In the experimental publishing master’s course, the wiki is very, very central to many things, it's very central to the course. It's used as a calendar, as a personal notebook, as a syllabus. It's the place to collect all the syllabi. It's an archive. It's many things. And I think that has been really, really important for both of us to see and feel the excitement and sort of understand from within the dynamics that a wiki creates. And at least for myself that was really the reason why I got interested in wiki publishing environments, because of searching for that combination of dynamics and sociality that a wiki can create and to try to bridge that to a publishing production moment. And also Simon has been working with wikis, like being interested in hypertext for your graduation project. And so the interest in wikis as a wiki as a mode of writing, I think is super important for us to be interested in this way of working.

Simon

And also learning at XPub about very simple ways of taking the content of a wiki and then bringing it into the format of a website or a PDF or something like that. At XPub, I learned how to do these things in an improvisational way. I wouldn't necessarily say it's like a structural part of what I was doing, but yeah, the publicness of the XPub Wiki at first is something which I found a bit daunting because everybody can see everything that you're doing. But at the same time, you also have a lot of control about how you want to organize your own user page and what you want to put there. And it's a great environment for being able to look at what other people are doing and have done over the years. I actually spent a whole year before I came to the Netherlands just lurking on the wiki for Piet Zwart Institute for Media Design. Mostly because it was a big decision I had to make, an expensive one, so I wanted to make sure it was the right one. I didn't have a chance to come to the open day, but I could see going back to 2011 or something, all of the work that people had done, all the questions they'd had, and to me it was this kind of radical openness that was really attractive. So when I first started writing on the wiki, I kind of understood already the publicness of it and who would be seeing it, and I felt okay about that. So I think that definitely changes things and it's different to say, if we were having a conversation about Wikipedia, which is a space that I don't feel comfortable writing within and also a very heavily contested space. So I think, you know, when we say Wiki, we also may have to make a distinction between which Wiki are we talking about. If the Piet Zwart one, yeah, great. The ones I've made myself, great. Wikipedia, maybe not so much. In terms of my comfort levels.

George

That's really nice. What Manetta was saying is that it's like this printing, practice or tool, whatever we want to call it, emerged from this background, right? Like the sociality and the community that went into printing instead of classic publication, which is you have a community separate to printing, and try and filter it through, that's really nice. And also, what you were talking about there as well, about accessibility, Simon, I think it's really amazing where you're like chatting about how it gave you from a distance such like intimacy with what was going on and gave you comfort. But what you were talking about with which wiki, and I think that's again, shapes it as a practice. It's like the wiki is the tool but it's about how you do the practice with that tool.

Manetta

I can't see the sociality and the technical setup separately any more from from each other if you want to talk about one particular wiki like what one wiki is never, never like another. It's really shaped by the people who are editing it, the relations between those people, the material written, also the way it is set up, who is running it, and all of those things, and how this software is structured in itself. It's just really important to not detach it from its social context.

I’m wondering what’s the breakpoint of feeling uncomfortable at first but ended up enjoying the openness of Wiki?

Simon

Again I'd have to say with openness, it can be good if you know the people who you're being open to or who's there. At the same time, I remember a big question that people had when I was studying at XPub and using the wiki was: What happens to the wiki after I graduate? What happens to my pages? Do they stay there? Also, it's possible for anybody to edit anyone's pages. So somebody could easily come to my user page and just delete everything. Of course, there's a user history there, and I can revert those changes, and I can go back.

But I remember also, there was a conversation around making a website for the Willem de Kooning Academy, which is the bachelor program of the Piet Zwart Institute. In 2020, they wanted to make a website to compensate for the fact there wouldn't be a graduation show, so they would have a graduation website. And this discussion about Wiki or WordPress was in the air. And it was a big concern to them, the openness of Wiki in that any student could go and edit any other student's page.

Manetta

Which is interesting because that fear comes from top down. But then, if you're in the middle of it, maybe you also have the fear that somebody will edit your page. But in reality, because it is so much embedded in a network of trust, I haven't heard of any occasion of things like this happening. I find it quite telling that in a sort of top-down situation, there's a fear that is then so strong, the degree of openness is not accepted. I mean there's lots to say though, I'm not here to idealise that degree of openness because it's quite something to run a wiki which is that open. In a sense of the responsibility that comes with it is something that can be talked about and should be talked about. Though I think, and especially in these days where people are being more and more aware that having their content on the open internet also means that there are crawlers and scrapers and anyone can read. In reality, not anyone is reading and it's really a place that is embraced by people around XPub, and in XPub, and then potential people coming to XPub. Although the question of openness gets more and more under pressure of those crawlers and things like that.

Sorry, I'm trying to make two points.

One about the crawlers and the second one is that openness sounds like it's open to anyone and in technical sense it is, but in practical reality you see the openness that this wiki has means that it mostly attracts people that somehow relate to the course. And because it is that open, it allows people that are not yet related to the course to still engage with that particular wiki, which is a porosity which I think does something very special. But now can then be put in contrast with the issue of the crawlers and the bots.

And yeah, so it's to be continued. It's really a complicated conversation.

George

Quickly just thinking about, it might be MIT or somewhere, their course website is completely open as well, like anyone can edit it and they've never had it. Like you said, thy never had any issues. I think it's like what Simon was touching on, there's a process for undoing things, you can see who's done it and cancel that account. There's these protocols in place that mean that if things do go wrong, we can deal with what goes wrong instead of trying to prevent things from going wrong, which also prevents certain things from going right.

We’re curious why do you like using Wiki? And before using Wiki, what other tools are you using? What are the frustration from the process of changing your tools?

Manetta

Yeah, there are many frustrations.

Simon

Maybe we should also disambiguate the different types of wiki software that we've used, because they're different from each other. When I talk about wiki, most of the time I'm talking about using the MediaWiki software. Because that's the one that's most familiar to me.

What I like about it is that there's a huge amount of people that are contributing to it and also making extensions for it. It's relatively easy to install. And because it's part of my practice and the people around me, it's often the first choice. But there are other wikis that we've worked with. We worked with and installed an iki Wiki, which is another system that's based on the Git version control history. And it's also being used for, say, the permacomputing.net . They use ikiwiki, and I think for them, they're using it because they can edit the wiki locally as a file and then push the commits. So it's very lightweight in terms of the network dependencies. Whereas I found it very frustrating for the project that we were using it for. It was very difficult to do things like understand how to show a gallery of images or things like that.

So yeah, for me, when I say I like using Wiki, I'm mostly saying I like using MediaWiki.

Manetta

There's so many ways to answer this question, but maybe to zoom out a little bit. For both of us this way of working with wiki publishing environments is part of a larger practice around making publications with free software, trying to move or moving away from, well, first of all, Adobe, which was our shared tool that we both learned to make publications with. That's how we got into the practice of graphic design. Then from an interest in learning about ways to generate publications, instead of making them through graphic user interfaces and visual tools, is what really grew my interest in workflows, in thinking about how a publication can be made collectively and how you can actually use all sorts of tools. And to combine them in all sorts of ways, to make custom ways of working, custom workflows that really fit a particular situation. So within that interest, there is another subsection that is really focused on using HTML and CSS to style and make the layout of those publications. But can also be done differently again.

So it's like once I moved away from working with these graphic user interfaces, I really entered into a way of working like a practice that feels super open-ended and is totally based on modularity, on combining all of these different tools. And so within that world, what I really like about working with wikis to make publications, is that they also become an archive of the material that you work with. Through the making of the printed publication, you actually also make a digital version that can be read online, that's like a practical website, but it also invites for writing in a different way. Like you can write in shorter snippets and recombine them for a printed publication in different ways. You can even make different versions out of the same material. You can write collaboratively, you can write, you can recombine those different elements over time differently. It really feels like it has the potential to write the body of text and then create publications out of that body of text in different ways. And that's what I really like about the wiki, that it has this potential to grow into an archive of practices. And by adding this PDF making functionality to a wiki, it feels like you add the ability to make a snapshot.

To make one particular sort of cut from an archive of materials. And that's maybe not how wiki publishing has always been used. For instance, in the Servpub project and also in the Volumetric Regimes project, the wiki was really there to produce a book. So then that creates a very different starting point for writing, because that comes with a particular idea of writing chapters, of order, of having a section with a biography, all these sorts of typical things that a book, or those particular books, will contain. But still within those more traditional editorial processes, the Wiki still allows for a very different way of working together. It's much less linear than you would have in more traditional workflows. You first need to finish the text, then have rounds of proof editing, copy editing, and all that, and only then do you send it to the designer, who would then do a back and forth with the editor to finish the layout. Here you can start making the layouts, in theory from the beginning, but I think you've been experiencing that this is hard in the context of the Servpub project, but it does create a very different dynamic in which everyone can see the final result. It also requires more involvement from editors, I believe, to think along the grain of this particular workflow. It is an experimental practice to make these particular books in this way, and it is not comparable with working in more traditional ways.

George

No, it's really good. And I like on that last point where you're talking about the difference of the more classic Wiki for print you're talking about where it's like building up a body of like writing and then forming a book from that in multiple structures and taking snapshots. Whereas like volumetric regimes and this project (Servpub) are more like the opposite end, but I still find that, you know, it's all about like orientation and even those books, even though they're more on the editorial process, they're trying to move towards.

And it's like we said, we're still learning or feeling it out the editing and the design process, but at least there's a space to do that as well. And start to try and do that anyway, which I thought was really nice.

And then the second point, if I'm not jumping too much, was also how you're chatting about moving from Adobe into like Wiki to print processes and chatting about how it can build, it feels like it can build up.

It's just making me think a lot about how Adobe being a for-profit company is like captures or tries to hold people in place, or with their products, or maintain specific dynamics. And it's a very closed ecology where it's like when you move out, even though it's harder, it's like you're adding to the psychology as you rise in it, as you design in it and as you like bring together these different add-ons.

Manetta

Thanks for emphasising that because that's a super important motivation to work in this way. That is the main motivation to work in this way to indeed not contribute, not be stuck in those world ecologies, but to see what happens when you start to become part of more open-ended ecologies.

Simon

Yeah, what happens and who you meet as well.

Manetta

What you learn from it, who you can work with.

Simon

What you learn from it is a big one. Adobe has a lot of different products and so a lot of people using them. There's a lot of information about how to use them. But I'd have to say, since I've started working with free and open source software, I've met people who are developing tools. I've met people who are using them. I've met people that are involved in trying to raise funds to support them, and there's a lot more complexity behind it than making a beautiful book.

I think those things are more intriguing for me, like the transformative things that happen on a social level through publishing, rather than just making a nice book.

To me, that seems to be a kind of limited as an outcome for publishing if it's just about aesthetics of how things look and if it's aligned to a grid or not.

Sunni

For my personal experience, it was really difficult for me to switch from using Adobe tools for years to using Wiki-to-print. But it really opens a door for me seeking more creative ways of working and thinking about the possibility of not using corporate tools for efficiency.

Manetta

I think if Wiki-to-print is your first step into that world, that's quite radical, because already just writing a small web page with some nice CSS styling and preparing that for print is super radical in my understanding of it. And it feels like here you got that, plus the layer of a wiki, plus the layer of what that does in terms of collaboration with a lot of other people. And then we didn't even talk about all the pre-press stuff that will come up when you start printing. Because these PDFs that roll out of browsers are not comparable at all with the PDFs that come out of Adobe InDesign. So it is quite rough. It's really a practice. It's really something that it is not comparable and is really a different world to work in.

Sunni

When I was chatting with Johanna, she was basically saying "this project feels like doing web development and design at the same time".

Manetta

That's actually really nice that you're saying that, because that's my intention. To not make those cuts between developers and designers, it's especially about sort of finding the interaction between the two. Also to come back to what was said about learning from these other people that you suddenly work with, like learning from developers and learning from people maybe involved on the more network or server level of things. All these things suddenly are coming together. It really matters how you configure the server. It really matters where that server is running. It matters how the development is done of the tool and it matters how the layout is being constructed aesthetically and all these things are relating to each other. It's very hard to cut them apart into even different roles that would be done by different people.

Speaking of the learning curve of wiki to print, I'm curious about how do you find sharing this practice to people who never use Wiki?

Manetta

It's a really good question. Because we have struggled with this, for instance, in the context of the research workshops. Because then the moment you're invited to bring something like Wiki2Print into a workshop that will involve, let's say, a group of 30 researchers coming from an academic background. If that workshop is then designed without the involvement of thinking what type of writing can be done from a wiki point of view, and so the ideas of writing collaboratively are just thought of separately from thinking, it's not done in conversation with the software and the setup and the practice of wiki publishing. And it becomes really hard to make that into something. And we struggled. Yeah, we really struggled.

Simon

And it's also a cultural thing. I mean, maybe I compare it to, say, using slang and certain types of language that you're comfortable with using with a group of people and then when you meet a different set of people and you use those words, then it's confusing and it can happen both ways. And it's very difficult to convey cultures because they're so, how would I say, they're not so explicitly there and when we meet each other. We don't think about, Oh well, I need to translate every single bit of slang that I use to somebody else. At the same time, it shouldn't necessarily be: Okay, we're going to use Wiki-to-print instead of an Adobe workflow, and therefore you must use it in this way that I've always used it.

It has to be some sort of common ground that you meet on. And it's difficult to do that, I think, in a short-term process.

Manetta

You need to take the time to find that common ground, and to find that space in between to make it interesting for all sides. I think it's still worked out in those particular settings. I think a wiki can definitely… also be used for more traditional ways of editing a book or maybe not as a writing environment. But more as an uploading environment. Let's say that the writing may have happened somewhere else, and then you upload. And still, there is something that create something interesting I find. But I think we came from being excited about wiki writing, that could be seen as an invitation to also really think about what modes of writing. We could explore together with these 30 people that we didn't know, and maybe we could write small wiki pages and then combine them, and then something could grow from it. Something could just emerge instead of starting from a structure and applying that to a wiki, which I think did work out.

And I'm still very happy with those newspapers that came out of those two particular workshops. But I think if we would have taken more time to find that common ground, it would have really changed the point that we departed from.

And we're still interested in finding a context to do that.

George

It kind of reminds me of how you were also talking about moving from Adobe to open source, or like this, where you kind of have to give up, or the practices aren't translatable as such.

It's like within software, there's strict limits, right? Where it's like, you're in Adobe, you have to do it this way. You're in CSS, you have to do it this way.

Whereas the wiki, it's more blurred, but you can upload something, but it's still there, I think. I definitely feel that there's also, like you said, having a common ground, or a background, or how we're talking about the X-Pub where it's like having a sociality or a energy that gets published or that you bring, maybe somewhat lacking or like.

It's like very important to this kind of work as well.

Manetta

Energy and having space to come together and enjoy being together, to work on that thing that you're working on together.

It's also very important to, once you enter into these, like on another level, when you enter into these community-based ways of working around publishing. It's also very important to find the joy of maybe coming together in an event or joining these summer schools that are organised, I mean, have been organised by, for instance, hackers and designers is one that I'd never joined myself, but I've seen people around me enjoying going there, meeting people.

I think...Simon and I organised the Publishing Partyline in 2022, which was really an important moment to feel the energy of that, quite big group of people coming together that all work in this particular way.

And so these moments of exchange are just really important for me. And needed to not feel like you're the only one stuck in a terminal and CSS style sheets to make this printed publication.

And you need to go through all these bugs and weird looking pages that you, and not aligning grids and all those things.

That's something that happens.

Simon

You need documentation and you don't know who to ask a question to and all these things.

With all these past projects, how does the structure of each project influence the technical structure of the coding architecture?

Simon

Do you mean like the way that Wiki to Print has been used, how that might influence a technical development, like adding a feature or something like that.

Sunni

That's the perfect way to put my question.

Manetta

Maybe that's a moment to talk about the different versions.

This particular software that the ServPub book is being created with is software that has been written by many, many hands and exists in many versions and is maybe more a practice than software in the end. This version that is running, I think we all together started to call it Wiki-4-Print, just to give it yet another name, but I don't think there are many changes to a version that is called Wiki-to-Print with the letters T-O, which is the version we (CC) use. Which is versioned from Wiki 2 Print with the number two, which Hackers and Designers is working with. And possibly also has multiple versions of because they made multiple publications with their version. But Wiki-2-print with the two is then yet also versioned from Martino's Wiki-to-PDF that he made for TITiPI, which TITiPI is using quite intensively in their wiki, in their media wiki. And Martino's version was based on the volumetric regimes version that I wrote that didn't have that collaborative element built-in. That part that is built into the MediaWiki itself, it wasn't there yet, but Martino. I don't know, so just to acknowledge that this is really entangled with many other versions of practice.

Simon

There are also other projects which aren't wiki but have a wiki logic, like Ethertoff, which is part of OSP's toolbox. And that also has a super long history.

I mean, that's using Etherpads, but with the same logic of like you can gather together a whole bunch of different pads to compile a publication.

And then that also has its own version trajectory into Etherport, which is being used by the Institute of Network Cultures and a group of other organisations at the moment. So there's the way of working, then there's the software, it gets very complex. And we can kind of chart a little bit of this in a way, but yeah, I mean also there may be somebody out there who's just like using something to pull text from a Wiki and putting it into a PDF that we don't know about.

But in terms of the version and changing things along the way, I mean the version of Wiki to print that we use, what is particularly different about the previous version of Wiki2print….

Manetta

Of the version from… Well, Hackers and Designers did a lot of work also on their version on....... Well, I remember what I changed to this particular Wiki2print that we use at CC is that you can click on update text and update media inside the MediaWiki itself.

And I think in the versions of Hackers and Designers and Martino, you had to go to another interface outside of the wiki to do those actions. I think Hackers and Designers added the style sheets to the talk page of a wiki so that you have them side by side. And that then inspired me to then add more buttons. I think, now I'm not 100% sure, but this is potentially one of the changes between the wiki to print for magazine design and the wiki to print that we're running at CC.

And then it's also running on Servpub.

George

But it really adds to the comments before of adding to the ecology and building some stuff, isn't it?

Manetta

And it's open-ended. Maybe there are more versions of these versions that we're not aware of. And that is really cool.

Conclusion and Design Colophon

Frustrations/difficulties/frictions also foster new ways of working, creating aesthetics that are particular to web technologies and software that wiki4print is built with. Learning and debugging become a social thing that slowly creates trust-based spaces for working together. For In-grid, working on this book is the start of tapping into the ecosystem of FLOSS design practices, and fostering spaces that attract like-minded practioners.

When we started working on this project, we had to challenge ourselves to take stock of the mainstream tools we instinctively used (Figma boards for moodboards, Photoshop for visual mockups, google fonts for font choices etc). Although we are computational practitioners who code creative software and do web development, we found that we made a division between design tools and software development tools.

In addition to using wiki4print, we followed some FLOSS Design principles and processes, including choice of fonts, and design values/ethics/considerations, licensing, questions of openness, federation, and other ways of organising. We used:

- Excalidraw for moodboards/brainstorming [10]

- Opensource font website for font choice (BADASS LIBRE FONTS BY WOMXN, openfoundry, velvetyne, The League Of Moveable Type etc...). All fonts used in this book are under the SIL Open Font License [11]

- Riseup pad for communication and documentation [12]

- Jitsi for videocalls [13]

Praxis Doubling: Misfitting Infrastructures

Contributors: In-grid (Batool, George, Katie)

(theory*practice)*2

Praxis itself is the combination of practice and theory, of code and conduct, and of docs and protocols. We posit Praxis Doubling as a term for bringing together different praxis, making room for them to permeate one another, to deviate actions and animate relations otherwise. Praxis doubling is itself a plural. The _ing on doubling is a process ongoing, a verb and an action that is multiplied through different orientations and approaches. By doubling praxis we aim to coalesce together, seduce and mutually shape feminist network praxises with critical access praxises. We aim to see how both of these approaches bring theory into collective action and not only make room for more accessible technical praxis, but also for their matters to become more frictious and disputed.

To make-sense of these technical network relations In-grid has built up a debugging practice around technical docs. Technical documentation is a resource that explains processes and practices that make up technical infrastructures. This collective debugging praxis came about when we came in touch with Servpub's table of feminist network praxis, and brought with us our own background of collective access praxis. By disobediently making room at this collective table, we aimed to make-sense of our misffiting with the inherited figures and imaginaries of network infrastructures and their technical docs. Through accepting misfittings we can disorient dialogues towards forming our own collective counter imaginaries and figures which can reshape their limits, and what is backgrounded within a single praxis. Here, we will outline how we have come to practice Praxis Doubling, and the methods we have used to facilitate this mingling of praxis.

Methods

The practices we describe here are ones that have emerged through an entanglement between disciplinary conventions and our own dis-abilities to fit within them. We engage with time scarcity, technical language hegemony and the expectations of productivity from the situated-ness of our accessibility needs and political ethics. This chapter expands on the ways in which we put-into-practice these needs and ethics, going through the process of working as a computational artist collective and how we approached creating critical documentation for the technical infrastructure of Servpub. We will stop to reflect on the points where the tools we work with created frictions that halted the alleged smoothness of technological processes to a stop, and will expand on the ways in which we worked around, through, and within these tools to make room for ourselves and each other (Rice et al., 2024). Some of these ways include approaches to time management and note-taking, deliberately unpacking or abandoning technical terminology, incorporating anecdotal situations rather than writing for a universal user and critically examining the political implications of names and logos of different tools. The technical documentation that is the outcome of this nebulous process is presented here as one offering of what a doubling of praxis may look like. We have transcluded excerpts from the technical documentation to exemplify this. We also acknowledge that the duality held within the double is not capacious enough to contain the multitude of difference and mis-fittings that the tools and conventions we confronted try to erase. This chapter contains the doubling(s) of theory and practice that emerged from our particular confrontation with building this infrastructure as artists, technologists and crip, neurodivergent and queer peers. We will go through some of our work modalities, to confronting specific tools and their frictions and some methods for making room for misfitting within them.

Background to In-grids Docs Praxis

To describe why the Servpub docs look and work the way they do, we must first (briefly) explain how In-grid as a collective works. Specifically, the processes that make it accessible for us to work together. The number of In-grid members hovers around 13-15 active members at any given time. Of that group, smaller groups cluster around specific projects and streams of work where approximately 4-6 members focus on a project at a time. When a proposed project garners the interest of enough members to make it feasible, we then confront the material conditions around everyones time and capacity, specifically the conditions that are a result of fractional and/or precarious work commitments. We work around that by allowing for some inefficiencies like last minute drop-outs and confirmations for joining meetings and working sessions, as well as caring for those returning after a several months break to rejoin a stream of work. We are also quite promiscuous as a collective and enjoy collaborating with a range of individuals beyond In-grid's already intersectional members. For us, this doesn't dilute who we are but brings in a wide rage of expertise and perspectives that we feel outweighs an experienced or expert individual. So while everyone has the opportunity to contribute to our ways of collaborating, we agreed early on to not silo off our different skills into roles, determined specialisms and isolated/ing processes but to make room for them to be shaped by bodies inside and outside of our collective. Not only did this orient our collective towards skill and knowledge sharing in and through practice, but it also made room for projects to be more accessible to collaborators, where otherwise there might be social, technical or capacity-based barriers. We have found that even though caring for this wide range of perspectices, practices and politics takes a lot more labour, it offers room for these approaches to multiply, for them to more than double, and for us to unfold situated praxis from specific projects and relations, such as the docs and workshops we share here.

Abundant notes, better make some room for them