Collectivities and Working Methods

Pad for working https://ctp.cc.au.dk/pad/p/servpub_methods

Coordinator: Winnie & Geoff

Contributors: In-grid, CC, Systerserver, Winnie & Geoff, Christian and Pablo

<unicode> ͚ ཀྵ 書 📖</unicode>

What does it mean to publish? Put simply, publishing means making something public (from the Latin publicare, ‘make public’), but there’s a lot more at stake, not simply concerning what we publish and for who, but how we publish. It is inherently a social and political process, and builds on wider infrastructures that involve communities and build publics, and as such requires reflexive thinking about the systems we use to facilitate the distribution, provision and movement of things as part of the underlying structures of organisational forms. In other words, publishing entails understanding the political-economic forces and socio-technical infrastructures that shape it as a practice.

This book is an intervention into these ongoing debates, emerging out of a particular history and experimental practice often associated with collective struggle.[1] It is shaped by the collaborative efforts of various collectives, operating both within and beyond academic contexts (hopefully undermining the distinction), all invested in the process of how to publish outside of the mainstream commercial and institutional norms of how we conceive of publications.[2] So-called "predatory publishing" has become the default business model for much academic publishing, designed to lure career-minded researchers into such things as paying fees for low quality services.[3] For the most part, academics are unthinkingly complicit, or compelled by a system that values metrics above all else, and tend not to consider the means of publishing as intimately connected to the argument of their papers. As a result there's often a disjunction between form and content.

Public-ation

Despite its apparent recuperation, the ethics of Free/Libre and Open Source Software (FLOSS) provides a foundation for alternative approaches, as it places emphasis on the freedom to study, modify and share information.[4] These are surely core values for any book project that wants to reach a wide readership, enabling modification and versioning within a broader and expandible community of use.[5] What FLOSS and experimental publishing have in common is the need to address the intersection of technology and sociality, and support communities to constitute themselves as publics not simply in terms of the ability to speak and act in public, but in constructing their own platforms beyond passive consumption, what Christopher M. Kelty has referred to as a "recursive public":

A recursive public is a public that is vitally concerned with the material and practical maintenance and modification of the technical, legal, practical, and conceptual means of its own existence as a public; it is a collective independent of other forms of constituted power and is capable of speaking to existing forms of power through the production of actually existing alternatives.[6]

Instead, and despite the widespread adoption of open access principles in academic publishing, relatively little has actually changed in practice and distribution is still largely organised behind pay-walls and reputation economies. It's important to add, that even when open access is adopted, for the most part it remains controlled by a select few companies that operate oligopolistic structures to protect their profit margins.[7] Open source simply becomes a smokescreen for business as usual much like greenwashing.

This book is an attempt to draw some red lines here concerning the historical and material conditions for the production and distribution of books, and to offer a critical alternative which is less extractive in terms of the resources and labour power engaged. Our concern lies in the disjunction between the critical rigour of academic texts and the conventional, often uncritical, modes through which they are produced. They lack criticality in other words, and by criticality, we mean to go beyond a criticism of conventional publishing and to further acknowledge the ways in which we are implicated at all levels in the choices we make when we engage with publishing practice, from attention to tools we use to the wider infrastructures within which they and we operate. It is this kind of reflexivity that has guided our approach throughout our project — moving beyond the notion of the book as a discrete object and instead conceiving it as a relational assemblage in which its constituent parts mutually depend on and transform one another.

Infrastructure

We have adopted the phrase "publishing as infrastructure" because we want to stress these wider relational properties and how power is distributed, as part of the hidden substrate that includes our tools and devices but also logistical operations, shared standards and laws, as Keller Easterling has put it.[8] Infrastructure allows information to invade public space, she argues (just as architecture was once killed by the book with the introduction of the Gutenberg printing press). This is why it is important to not only expose its workings but also acquire the skills -- both technical and concpetual -- to make alternatives.

Some of the most radical changes to the globalizing world are being written, not in the language of law and diplomacy, but in these spatial, infrastructural technologies — often because market promotions or prevailing political ideologies lubricate their movement through the world." (Easterling)

The argument of Easterling, and others, recognises that infrastructure has become a medium of information and mode of governance, exercised through actions that determine how objects and content are organised and circulated. Susan Leigh Star has also emphasised the point that "infrastructure is a fundamentally relational concept", organised through practices and wider ecologies.[9] Put simply, infrastructures are something other things “run on”, consisting mainly of “boring things",[10], and the trick of the tech industry is to make these operations barely noticeable. In this sense infrastructure is ideological as it hides its underlying structures and naturalises its operating system. The infrastructures of publishing are arguably all the more powerful as they distribute information on the page through words and at the same time through the wider operating systems on which they are dependent. If we are to reinvent academic publishing, this must occur at every layer and scale — what we might call a full-stack transformation, spanning everything from infrastructure and workflows to authorship, design, and distribution.

Backround/foreground

In summary, the book you are reading is a book about publishing a book, a kind of manual for thinking and making one differently, drawing attention to these wider structures and recursions. It sets out to acknowledge and register its own process of coming into being as a book — as an onto-epistemological object — to highlight the interconnectedness of its contents and the infrastructures through which it takes shape in becoming (a) book.

Given these concerns, it seems perverse that academic books are still predominantly written by individual authors and distributed by publishers as fixed objects. It would surely be more logical to incorporate practices such as collaborative authorship, community peer review and annotation, the ability to update through iterative processes that allow for the development of versions over time, as Janneke Adema has argued, “an opportunity to reflect critically on the way the research and publishing workflow is currently (teleologically and hierarchically) set up, and how it has been fully integrated within certain institutional and commercial settings.”[11] A processual approach allows for other possibilities that draw publishing and research processes closer together, and within which the divisions of labour between writers, editors, designers, software developers merge in non-linear workflows. Put simply, our point is that by focussing on the practice of publishing in this way, through the sharing of resources and modification of texts, generative possibilities emerge that breaks out of protectionist conventions perpetuated by tired academic procedures (and tired academics) that assume knowledge to be producedin standardised ways and imparted in linear directions.

An alternative approach such as ours is not new. It draws on multiple influences, from the radical publishing tradition as well as other experimental attempts to make interventions into research cultures. We might immodestly point to some of our own previous work too, including Aesthetic Programming, a book about software, imagined as if it were software.[12] The book draws upon the practice of forking in which programmers are able to update or improve software — making changes and submitting merge requests to incorporate updates — as part of a community of shared practice and trust. This is common practice in free and open software development in which developers place their programs in version control repositories (such as GitLab). The book explored how the concept of forking could inspire new practices of writing by offering all contents as an open resource, with an invitation for other researchers to fork a copy and customise their own versions of the book, with different references, examples, reflections and new chapters open for further modification and re-use.[13] By encouraging new versions to be produced by others, the idea was to challenge publishing conventions and make effective use of the technical infrastructures through which it was distributed. Clearly wider infrastructures are especially important to understand how alternatives emerge from the need to configure and maintain more sustainable and equitable networks for publishing, and to be sensitive to the communities that contribute to this shared effort, as readers, writers and programmers alike. All this goes against academic conventions that require books to be fixed in time and follow narrow conventions of attribution and copyright.

The collaborative workshops co-organised by the Digital Aesthetics Research Center at Aarhus University and transmediale festival for art and digital culture based in Berlin provide a further example in practice. Since 2012, these workshops have attempted to make interventions into how academic research is conducted and disseminated.[14] Participants are encouraged to not only engage with their research questions and offer critical feedback to each other through an embodied peer review process, but also to engage with the conditions for producing and disseminating their research as a shared intellectual resource.

The Minor Tech workshop in 2023 made these concerns explicit, setting out to address alternatives to major (or big) tech by drawing attention to the institutional hosting, both at the in-person event and online.[15] In this way, the publishing platform developed for the workshop can be understood to have a pedagogic function allowing for thinking and learning to take place as part of the wider socio-technical apparatus.

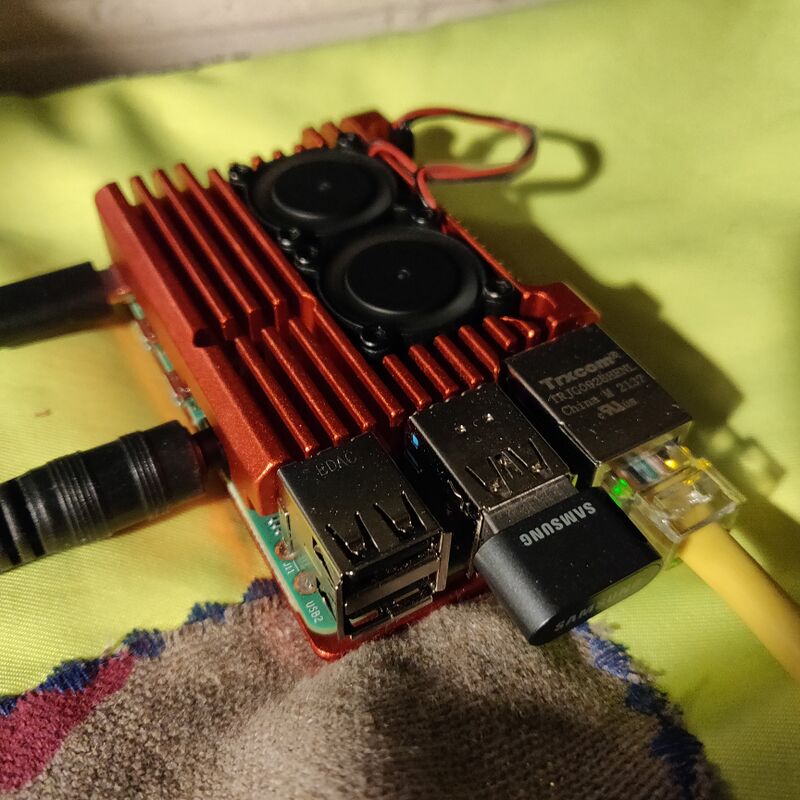

The 2024 workshop Content/Form, further developed this approach in collaboration with Systerserver and In-grid, using the ServPub project as a technical infrastructure on which to build the pedagogy, and to stress that the tools and practices for our writing shape it whether acknowledged or not.[16] The process of setting up the server is described in subsequent chapters, but for now it is important to register how its presence in the same space as the workshop helps to place emphasis on the material conditions for collective working and autonomous publishing.

Server issues

In an academic context it is no easy matter to work in this way, as infrastructures are mostly locked down and outsourced to third parties. At Aarhus University, the CTP (critical-technical practice) server is an ongoing attempt to build and maintain an alternative outside of institutional constraints. This was a response to the problem of allowing access to outside collaboration and running software that was considered a security threat, and therefore needed careful negotiation with IT procedures and policies.[17] In constrast to standard provision, the server is less reliable and does follow official standards of efficiency, scalability, productivity, accessibility, optimisation and immediacy. Issues of ongoing maintenance become foregrounded and the shared responsibility of the group required some agreed code of conduct. It needs care, but rather differently to the ways care has become weaponised in mainstream institutional contexts. Care has become something that institutions purport to do, with endless policies around well-being and support, but without threatening the structures of power that produce the need in the first place.[18] Something more along the lines of "pirate care" is required, in which the coming together of care and technology can question "the ideology of private property, work and metrics".[19] Pirate ethics in this sense comes close to the work of feminist scholars such as Maria Puig de La Bellacasa who draw attention to "relations [that] maintain and repair a world so that humans and non-humans can live in it as well as possible in a complex life-sustaining web" We borrow this quote from The Pirate Care Project, see Maria Puig de La Bellacasa, Matters of Care: Speculative ethics in more than human worlds (University of Minnesota Press 2017), 97. Feminist servers also follow these principles, wherein practices of care and maintenance are understood as acts of collective responsibility.

link=File:Rosa2022.jpg|frameless Caption: rosa, a feminist server, in ATNOFS.

Caption: rosa, a feminist server, in ATNOFS.

A further inspirational project is "A Transversal Network of Feminist Servers" (ATNOFS) formed around intersectional, feminist, ecological servers whose communities exchanged ideas and practices through a series of meetings in 2022.[20] As the website notes outline, the project responded to the need for federated support for self-hosted and self-organised computational infrastructures in The Netherlands (Varia, LURK), Romania (hypha), Austria (esc mkl), Greece (Feminist Hack Meetings) and Belgium (Constant).[21]

At the centre of ATNOFS was rosa, a feminist server (see image above), collaboratively created as part of the project, a travelling infrastructure for documentation, collective note-taking, and publishing to connect people and things. The naming and use of terms was considered important in the male-dominating discourse of technology. "We’ve been calling rosa ‘they’ to think in multiples instead of one determined thing / person. We want to rethink how we want to relate to rosa".[22] In this way the server itself performs an identity function that broadly reflects feminist values — acting not as a neutral or passive machine, but as a situated, relational agent of care and resistance. It is a "situated technology", drawing on Donna Haraway’s concept of “situated knowledges”[23] — emerging from particular bodies, contexts, cultures, and relations of power.

Is it about self definition? – I am a feminist server.

Or is it enough if they support feminist content?

It is not only about identifying, but also whether their ways of doing or practice are feminist."[24]

It is clear that to describe a server as feminist is not merely to identify who builds or uses it, but to consider how it is produced, maintained and engaged with— in opposition to the patriarchal, extractive logic of mainstream computing. However, without careful qualification, the idea of a feminist server risks defaulting to white, ableist, and cis-normative assumptions, potentially obscuring interconnected systems of oppression. An intersectional approach is needed. In the publication it is argued that a focus on resources can connect issues related to "labour, time, energy, sustainability, intersectionality, decoloniality, feminism, embodied and situated knowledges. This means that, even in situations focusing on one specific struggle, we can’t forget the others, these struggles are all linked."[25]

It is with this in mind that we have tried to engage more fully with affective infrastructures that not only support alternative forms but are underpinned by intersectional and feminist methodologies. Systerserver, for instance, as a feminist, queer, and anti-patriarchal network, prioritises care and maintenance, offers services and hosting to its community, and acts as a space to learn system administration skills and inspire others to do the same.[26]

Socio-technical forms

We hope it is clear by now that our intention for this publication is not to valorize feminist servers or free and open-source culture but to stress how technological and social forms come together, thereby to encourage reflection on shared organizational processes and power relations. This is what Stevphen Shukaitis and Joanna Figiel have previously clarified in "Publishing to Find Comrades," a phrase which they borrow from the Surrealist Andre Breton:

“The openness of open publishing is thus not to be found with the properties of digital tools and methods, whether new or otherwise, but in how those tools are taken up and utilized within various social milieus."[27]

Their emphasis is not to publish pre-existing knowledge and communicate this to a fixed reader — as is the case with much academic publishing — but to work towards developing social conditions for the co-production of meaning and action. We publish in solidarity with others.

Thus, publishing is not something that occurs at the end of a process of thought, a bringing forth of artistic and intellectual labor, but rather establishes a social process where this may further develop and unfold. In this sense, the organization of the productive process of publishing could itself be thought to be as important as what is produced.[28]

We agree. Their article discusses how the collectives involved in autonomous publishing invent organisational forms that come close to political organising. Thus the process of making a book can be seen to be not merely a way to communicate the contents but to invent organisational forms with wider political purpose. Can something similar be said of the ServPub project and our book? Maybe. Perhaps the attention to infrastructure is significant here, as well as the affordances of the tools we use, in allowing for reflection on creative labour, the conditions of production, and sustainability of our practice as academics and cultural workers. Moreover, the political impulse for our work draws upon the view that tools of oppression offer limited scope to examine that oppression and their rejection is necessary for genuine change in publishing practices.[29]

[insert an image of etherpad]

For this book, we have used Etherpad for drafting our texts, a free and open source writing software, to coordinate, collaborate, and write together asynchronously. As an alternative to working with Microsoft teams or Google docs, a pad allows for a different model for the organisation and development of projects and other related research tasks that tend to follow a prescribed division of labour. To explore the public nature of writing, Etherpad makes the writing process visible — anyone of us can see how the text evolves through additions, deletions, modifications, and reordering. One of its features is the timeline function (called Timeslider in the top menu bar), which allows users to track version history and re-enact the process. This transparency over the sociality and temporality of form not only shapes interaction among writers but also potentially engages unknown readers, before and after the book itself.[30] Another feature is that authors are identifiable through colors, usernames are optional with writing anonymous by default. Martino Morandi has described this as “organizational writing”, quoting Michel Callon’s description of “writing devices that put organization-in-action into words” and how writing in this way collectively “involves conflict and leads to intense negotiation; and such collective work is never concluded, for writing leads to endless rewriting.”[31]

Logistics

Apart from writing the book, and drawing attention to its organisational aspects, it is important to register that we are collectively involved in all aspects of its making. The production process — including writing and peer review, copyediting and design — is reflected in the choice of the tools and platforms that we are using. Using MediaWiki software and web-to-print layout techniques, ServPub is an attempt to circumvent standard academic workflows and instead conflate traditional roles of writers, editors, designers, developers alongside the affordances of the technologies. To put it bluntly, this means rejecting proprietry software such as Abode Creative Cloud and designing otherwise, with the ironic naming of Creative Crowds a reminder of an alternative approach. Indeed, the distributed nature of this process is reflected in the combinations of those involved, directly and indirectly. This includes building on the work of others involved in the development of the tools such as the various iterations of 'wiki-to-print' and 'wiki2print', which In-grid have further adapted as 'wiki4print' for this book.[32] The book object is just one iteration of a complex set of interactions and exchange of knowledge.

As mentioned, the traditional divisions of labour are somewhat collapsed, and the activities that make up the publishing pipeline are reinvented in relation to the various tools and the organisational forms they support. This is inevitably not without its challenges, especially when such a diverse group is involved, each with their own experiences, positionalities, life and employment situations. One of the many challenges of a project like this is to account for these differences, which include the complexities of free and paid labour. We have tried to address or acknowledge potential "discomfort" associated with the project throughout our work together, and see this as a requirement when engaging technology and grassroots collectives who often remain suspicious of academia. In the article by Shukaitis and Figiel, these tensions are characterised as a question of who has access to resources and the reliance on forms of free labour in cultural work.[33] Mirroring what takes place in the arts, they refer to how unseen and unpaid labour is central to academic publishing, in particular the peer review process, if not the writing too.[34] Careful consideration must be given to the working conditions and infrastructures for publishing, with sensitivity to all aspects of intersectionality, such as how race, gender, class, sexuality, and ability interact and overlap to allow access to the resources we are able to draw upon, and questioning which particular kinds of labour are valorised or not.

This attentiveness to the social and material conditions of publishing — as a means of establishing new social relations and engaging critically with infrastructure — resonates with what Fred Moten and Stefano Harney describe as the "logisticality of the undercommons".[35] In The Undercommons, they refer to how "logistics" — the invisible infrastructures that move people, goods, and information — are central to how institutions function under global capitalism. The "undercommons" refers to spaces or modes of being that exist outside of formal institutions like the university or the state. It's about informal, "fugitive" and diverse ways of knowing, relating, and organizing that don’t reproduce existing power structures and refuses easy resolutions and answers. This also resonates with David Graeber’s rejection of academic elitism and instead embraces lived experience and collective imagination.[36] Like Jack Halberstam’s articulation of "low theory" in The Queer Art of Failure, this a way to think with failure and engage theory from the margins, rather than from rigid and legitimated systems of knowledge often published in journals.[37] The logisticality of the undercommons points to questions of how we share resources, how we organize together, and how we circulate ideas — an infrastructural issue for publishing in our terms.

As the publisher of Harney and Moten's work (and our book of course), the project of Minor Compositions follows such an approach. The naming of "minor compositions" resonates too, alluding to Deleuze and Guattari's book on Kafka, the subtitle of which is "Towards a Minor Literature".[38] As mentioned, we previously used this reference for our 'minor tech' workshop[39] to question 'big tech' and to follow the three main characteristics identified in Deleuze and Guattari's essay, namely deterritorialization, political immediacy, and collective value. As well as exploring our shared interests and understanding of minor tech in terms of content, the approach was to implement these political principles in practice. This approach maps onto our book project well and its insistence on small scale production, as well as the use of the servpub infrastructure to prepare the publication and to challenge the operations of "big" publishing. The project of Minor Compositions is explained by Stevphen Shukaitis as coming, "not from a position of ‘producer consciousness’ ('we’re a publisher, we make books') but rather from a position of protagonist consciousness ('we make books because it is part of participating in social movement and struggle')."[40] Explicit connection is made to the post-Marxism of autonomist thinking and practice, building on the notion of collective intelligence, or what Marx referred to, in "Fragment on Machines", as general (or mass) intellect.[41] General intellect remains a useful concept for us as it describes the coming together of technological expertise and social intellect, or general social knowledge, and recognition that although the introduction of machines under capitalism broadly oppresses workers, they also offer potential liberation from these conditions. The same is the case with infrastructure as we have tried to argue.

In the case of publishing, our aim is to extend its potential beyond the functionary role to make books as finished objects and generate surplus value for publishers, and instead engage with how thinking is developed with others as part of social relations and organisational forms. In our interview sessions with the organsiers of Open Book Futures (our sponsors), collectives have identified that working together is a way to learn together, a way to share skills and knowledge, often taken from experience of computational practice and then applied to publishing, and trying to thinking outside of the established conventions of both (even if publishing is relatively unknown, as identified by In-grid). Systerserver, on the other hand, build on their experience making zines for technical documentation, and recognise that what we refer to as academic publishing comes with its own protocols and conventions that tend to go against the grain of radical self-organisation. Radical referencing is part of this, as a way to address the canon and offering other viewpoints and voices that tend to be left out of the discussion. The book has tried to take this approach seriously, diverting from the reliance on big name academics in recognition that ideas evolve far more organically through conversations and encounters in everyday situations. The last chapter explores this in more detail and it becomes clear that hierarchies of knowledge are reinforced through referencing and the cultural capital attached to certain theorists and theory.[42] We are also introduced to Sara Ahmed’s intervention in the politics of referencing in which white men are excluded from citation.[43] If we are to take an intersectional approach here, then other exclusions need to be engaged that relate to the broader project of epistemic justice.

Structure of the book

Each chapter unpacks practical steps alongside a discussion of the implications of our approach.

[go on to describe each chapter in detail]

Autonomous publishing

The different groups have identified some of the challenges and opportunities in making a book like this. In our interview sessions they state that working together is a way to express autonomy and recognise our dependencies. This relates to the issue of consent according to one of the members of In-grid, and a baseline solidarity about what everyone is working towards and agreed to. "We're choosing to be to be reliant on software's open source practices, drawing upon the work of other communities, and in this sense are not autonomous". But it is important to clarify what we mean by autonomy or autonomous publishing in this connection. There’s a complex discussion here that we simply don’t have time to rehearse in this book but broadly connects to the idea of artistic autonomy and practices to undermine the kinds of autonomy attached to the formalist discourse of Clement Greenberg and others.[44] One way to understand this better would turn to the etymology of the term which reveals ‘autos’ as self and ‘nomos’ as law, together suggesting the ability to write your own laws or self-govern. But clearly individuals are not able to do this in isolation from social context, and any laws operate in social context. It is no wonder much contemporary cultural practices are performed by self-organised collectives that both critique and follow institutional structures, managerial and logistical forms. No different is our own nested formation of a collective of collectives.

Making reference to the post-Marxism of 'autonomia' it allows us to draw attention to our understanding of the value of labour in our project as well as subjectivity of the worker.[45]There's much more to say here, and about the context of Italy, but we perhaps stray from the point of the book. For more on Autonomia, see Sylvère Lotringer and Christian Marazzi, eds., Autonomia: Post-Political Politics (Semiotexte, 2007).</ref> Whereas Capital valorises work, and tries to re-establish the wage-work relation at all costs (even when speaking of unpaid house work), an autonomist approach politicises work and attempts to undermine spurious hierarchies related to qualifications and different wage levels from full-time employment to casualisation in ways that resonate with the different statuses across our team. This has relevance, especially in the collective formation of collectives where some are waged and others not, some positioned as early career researchers and others with established positions. Who and how we get paid or gifts, and what motivates this effort is variable and contested. As we have suggested earlier, that's important but not really the point.

All the same, a more anarchist position is an attempt to dismantle some of the centralised (State-like) structures and replace them with more distributed forms that are self-organised. And this is not to say that power goes away. In our various collectives this power relation leads to inevitable feeling of unease as our precarities are expressed differently according to the situations in which we find ourselves. When we recognise the system is broken, subject to market forces and extractive logic, Systerserver remind us that repair is possible, along with a sense of justice, other possibilities that are more nurturing of change. We'd like to think that our book is motivated in this way, not to just publish our work to gratify ourselves or develop academic careers or generate surplus value for publishers or Universities, but to exert more autonomy over the publishing process and engage more fully with publishing infrastructures that operate under specific conditions. Our aim is to rethink publishing infrastructure and knowledge organization, and offer a viable alternative which can support new and existing publishing initiatives and collective organisation. The publication that emerged from this process reflects ongoing conversations and collective writing sessions between the various communities that have supported the development of our ideas in such a way that we no longer know who thought what. No matter. The book is a by-product of these lived relations and oragnisational forms, open to ongoing transformation and the creation of differences, and operating across modes of knowing and becoming.

index.php?title=Category:ServPub

- ↑ Janneke Adema, "Experimental Publishing as Collective Struggle: Providing Imaginaries for Posthumanist Knowledge Production", Culture Machine 23 (2024), https://culturemachine.net/vol-23-publishing-after-progress/adema-experimental-publishing-collective-struggle/

- ↑ Influential here is the Experimental Publishing masters course (XPUB) at Piet Zwart Institute in Rotterdam, where students, guests and staff make 'publications' that extend beyond print media. See: https://www.pzwart.nl/experimental-publishing/special-issues/. Amongst others, two other grassroot collectives based in the Netherlands are also significant, Varia and Hackers & Designers, and in Belgium, Constant and Open Source Publishing, who have focused on developing and sharing free and open source publishing tools, including web-to-print techniques. See https://varia.zone/en/tag/publishing.html and https://www.hackersanddesigners.nl/experimental-publishing-walk-in-workshop-ndsm-open.html. The colophon offers a more comprehensive list of the geneology of these tools.

- ↑ Jeffrey Beall, Predatory publishers are corrupting open access, Nature 489, 179 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/489179a.

- ↑ Mathias Klang, "Free software and open source: The freedom debate and its consequences." First Monday (2005): https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/1211.

- ↑ Lucie Kolb, Sharing Knowledge in the Arts: Creating the Publics-We-Need. Culture Machine 23 (2024): https://culturemachine.net/vol-23-publishing-after-progress/kolb-sharingknowledge-in-the-arts/.

- ↑ See Christopher M. Kelty, Two Bits: The Cultural Significance of Free Software (Duke University Press, 2020), 3; available as free download at https://twobits.net/pub/Kelty-TwoBits.pdf.

- ↑ Leigh-Ann Butler, Lisa Matthias, Marc-André Simard, Philippe Mongeon, Stefanie Haustein, "The oligopoly’s shift to open access: How the big five academic publishers profit from article processing charges", Quantitative Science Studies (2023) 4 (4): 778–799. https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00272.

- ↑ Keller Easterling, Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space (London: Verso, 2014).

- ↑ Susan Leigh Star & Karen Ruhleder, Steps Toward an Ecology of Infrastructure: Design and Access for Large Information Spaces, Information Systems Research 7(1) (1996), 111-113, https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.7.1.111. Thanks to Rachel Falconer for reminded us of this reference.

- ↑ Susan Leigh Star. The Ethnography of Infrastructure. American Behavioral Scientist 43(3) (2016): 377–391. doi: 10.1177/00027649921955326.

- ↑ The Community-led Open Publication Infrastructures for Monographs research project, of which Adema has been part, is an excellent resource, including a section "Versioning Books" from which the quote is taken, https://compendium.copim.ac.uk/. Also see Janneke Adema’s "Versioning and Iterative Publishing" (2021), https://commonplace.knowledgefutures.org/pub/5391oku3/release/1 and “The Processual Book How Can We Move Beyond the Printed Codex?” (2022), LSE blog, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/lsereviewofbooks/2022/01/21/the-processual-book-how-can-we-move-beyond-the-printed-codex/; Janneke Adema and Rebekka Kiesewetter, Experimental Book Publishing: Reinventing Editorial Workflows and Engaging Communities (2022), https://commonplace.knowledgefutures.org/pub/8cj33owo/release/1.

- ↑ Winnie Soon & Geoff Cox, Aesthetic Programming (London: Open Humanities Press, 2021). Link to downloadable PDF and online version can be found at https://aesthetic-programming.net/; and Git repository at https://gitlab.com/aesthetic-programming/book. See also Winnie Soon, "Writing a Book As If Writing a Piece of Software", in A Peer-reviewed Newspaper about Minor Tech, 12 (1) (2023).

- ↑ In response to the invitation, Mark Marino and Sarah Ciston added chapter 8 and a half (sandwiched between chapters 8 and 9) to address a perceived gap in the discussion of chatbots. Their reflections on this can be found in an article, see Sarah Ciston & Mark C. Marino, “How to Fork a Book: The Radical Transformation of Publishing,” Medium, 2021, https://markcmarino.medium.com/how-to-fork-a-book-the-radical-transformation-of-publishing-3e1f4a39a66c. In addition, we have approached the book’s translation into Chinese as a fork. See Shih-yu Hsu, Winnie Soon, Tzu-Tung Lee, Chia-Lin Lee, Geoff Cox, “Collective Translation as Forking (分岔),” Journal of Electronic Publishing 27 (1), pp. 195-221. https://doi.org/10.3998/jep.5377(2024).

- ↑ Details of the workshops and associated publications can be found at https://aprja.net/. To explain, an annual open call is released based loosely on the transmediale festival theme of that year, targeting diverse researchers. Accepted participants are asked to share a short essay of 1000 words, upload it to a wiki, and respond online using a linked pad, as well as attend an in person workshop, at which they offer peer feedback and reduce their texts to 500 words for publication in a “newspaper” that is presented and launched at the festival. Lastly, the participants are invited to submit full length articles of approximately 5000 words for the online open access journal APRJA, https://aprja.net/. The down/up scaling of the text is part of the pedagogical design, condensing the argument to identify key arguments and then expanding it once more to substantive claims.

- ↑ The newspaper and journal publications in 2023 and 2024 were produced iteratively in collaboration with Simon Browne and Manetta Berends using wiki-to-print tools, based on MediaWiki software, Paged Media CSS techniques and the JavaScript library Paged.js, which renders the PDF, much like this book. As mentioned, an account of the development of these tools is included in the colophon, including, for example, wiki-to-print development and F/LOSS redesign by Manetta Berends for Volumetric Regimes edited by Possible Bodies (Jara Rocha and Femke Snelting) (Open Humanities Press, 2022), available for free download at http://www.data-browser.net/db08.html.

- ↑ More details on the Content/Form workshop and tools as well as the newspaper publication can be found at https://wiki4print.servpub.net/index.php?title=Content-Form. The research workshop was organized by SHAPE Digital Citizenship & Digital Aesthetics Research Center, Aarhus University, and the Centre for the Study of the Networked Image (CSNI), London South Bank University, with transmediale festival for digital art & culture, Berlin.

- ↑ Fuller description can be found at https://darc.au.dk/projects/ctp-server.

- ↑ See Nishant Shah, "Weaponization of Care", nachtkritik.de, 2021, https://nachtkritik.de/recherche-debatte/nishant-shah-on-how-art-and-culture-institutions-refuse-dismantling-their-structures-of-power.

- ↑ See "The Pirate Care Project", https://pirate.care/pages/concept/.

- ↑ A Traversal Network of Feminist Servers, available at https://atnofs.constantvzw.org/. The ATNOFS project drew upon Are You Being Served? A Feminist Server Manifesto 0.01, available at htps://areyoubeingserved.constantvzw.org/Summit_aterlife.xhtm. For a fuller elaboration of Feminist servers, produced as a collective outcome of a Constant meeting in Brussels, December 2013, see https://esc.mur.at/en/werk/feminist-server. Marloes de Valk contributed to the ATNOFS pubication and has also written about this extensively in her PhD thesis, The Image at the End of the World: Communities of practice redefining technology on a damaged Earth (London South Bank University, 2025).

- ↑ Part of our motivation for ServPub was to address the perceived need to develop a parallel community of shared interest around experimental publishing and affective infrastructures in London. We could see similar initiatives elsewhere, in particular in the Netherlands and Belgium, and were envious.

- ↑ See A Traversal Network of Feminist Servers (2024), https://atnofs.constantvzw.org/.

- ↑ Donna Haraway, "Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective", Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (Autumn 1988): 575–599. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066.

- ↑ ATNOFS, 160. The ATNOFS publication that emerged from these meetings and conversations was released in a manner that reflects the collective ethos of the project. A limited number of copies were printed and distributed through the networks of participants, and designed to be easily printed and assembled at home — reinforcing its commitment to collaboration.

- ↑ ATNOFS, 172.

- ↑ See https://systerserver.net/

- ↑ Stevphen Shukaitis & Joanna Figiel, "Publishing to Find Comrades: Constructions of Temporality and Solidarity in Autonomous Print Cultures," Lateral 8.2 (2019), https://doi.org/10.25158/L8.2.3. For another use of the phrase, see Eva Weinmayr, "One publishes to find comrades," in Publishing Manifestos: an international anthology from artists and writers, edited by Michalis Pichler (Cambridge MA: The MIT Press, 2018).

- ↑ Shukaitis & Figiel.

- ↑ As Audre Lorde famously puts it, "the master's tools will never dismantle the master's house". See Audre Lorde, The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House, available at https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/audre-lorde-the-master-s-tools-will-never-dismantle-the-master-s-house.

- ↑ Or, turns readers into writers as Walter Benjamin expressed it, in his 1934 essay "The Author as Producer", in Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings: Volume 2, Part 2, 1931-34 (Belnap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005), 777: "What matters, therefore, is the exemplary character of production, which is able, first, to induce other producers to produce, and, second, to put an improved apparatus at their disposal. And this apparatus is better, the more consumers it is able to turn into producers — that is, readers or spectators into collaborators."

- ↑ Martino Morandi, “Constant Padology,” MARCH, January 2023, https://march.international/constant-padology/. The source is Michel Callon’s “Writing and (Re)writing Devices as Tools for Managing Complexity,” in Complexities, John Law & Annemarie Mol (eds.) (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002), 203.

- ↑ Again, see the colophon for details.

- ↑ Shukaitis & Figiel. Athough it should be noted that they are mindful not to reduce everything to the question of remuneration.

- ↑ Shukaitis and Figiel cite Kathleen Fitzpatrick's Planned Obsolescence: Publishing, Technology, and the Future of the Academy (New York: New York University Press, 2011). On the related issue of unpaid female labour, see Silvia Federici, Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle (Oakland: PM Press, 2012).

- ↑ Stefano Harney & Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (Wivenhoe/New York/Port Watson: Minor Compositions, 2013).

- ↑ Thanks to Marloes de Valk for reminding us of this reference. See David Graeber, Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology (Prickly Paradigm Press, 2004).

- ↑ Jack Halberstam, The Queer Art of Failure (Duke University Press, 2011).

- ↑ Gilles Deleuze & Félix Guattari, Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature [1975], trans. Dana Polan (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1986).

- ↑ A Peer-Reviewed Journal About Minor Tech 12 (1) (2023), https://aprja.net//issue/view/10332.

- ↑ "About - Minor Compositions," excerpted from an interview with AK Press, https://www.minorcompositions.info/?page_id=2.

- ↑ Fragment on Machines is a passage in Karl Marx, Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy (Rough Draft), Penguin Books in association with New Left Review, 1973, available at https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1857/grundrisse/.

- ↑ In the last chapter, we cite Celia Lury's notion of ‘epistemic infrastructure’ – the organisational structures and facilities by which knowledge becomes knowledge, see Celia Lury, Problem Spaces: How and Why Methodology Matters (John Wiley & Sons, 2020), 3.

- ↑ Sara Ahmed, Living a Feminist Life (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016).

- ↑ For an account of the autonomy of art as a social relation, see Kim West's The Autonomy of Art Is Ordinary: Notes in Defense of an Idea of Emancipation (Sternberg Press, 2024).

- ↑ Autonomia refers to post-Marxist attempts to open up new possibilities for the theory and practice of workers' struggle in the 1970s following the perceived failure of strike action.