Coordinator: SysterServer with contributors: xm (ooooo), Mara and nate

"[T]echnologies are about relations with things we would like to relate to, but also things we don't want to be related to." (Femke Snelting in Forms of Ongoingness, 2018)

intro

Feminist networking is a situated, transgressive and technopolitical practice that comprises more-than-human relations, hardware, wetware and software, as well as material, affective and protocological dimensions. Networking can be laborious, an act of care, of weilding solidarities, of sharing and of growing alliances. It is a community practice, a way of staying connected and connecting anew, of looking for and cherishing those critical connections which are always already more than technical -- even though technologies and mediatic infrastructures are often involved in making and maintaining them. Feminists have long recognized the power that digital networking technologies hold for forming translocal movements, mobilizing and sharing information quickly and without mediators. But when it comes to practices of appropriating technology, and coming closer to the machines in ways that are 'unfaithful' to their militaristic and extractivist origins (Haraway), we sense a lot of hesitation, fear and structural obstacles in our feminist queer circles.

This is why, as trans*hack, cyber feminists, some of us take inspiration from the tactics of Queercore: How To Punk A Revolution. The documentary explores the rise of the queercore cultural and social movement in the mid-1980s, which channeled punk angst into a biting critique of societal homophobia. We introduce our feminist server's activities as a catalyst to push techno-feminism into existence and announce that we are here to stay. We set out to appropriate technology for and through our feminist networks, even amidst this current techno-fascist oppressive society.

Feminist networking involves two principles: 'Making space for ourselves*' [x] and 'choosing our* own dependencies'[x]. These principles embraces the feminist politics of embodiment, situatedness and consensual decision making. Feminist networking is not constrained to digital technologies, or even to the ways in which the internet works. (see the 'other networks' publication). But when we are talking about the internet and its potential for feminist networking, we need to move away from thinking of it as something we 'use', away from the cloudy image of cyberspace serving the extension and intensification of the logistics of capital and data power [x]. Instead, we need to understand feminist networking in regard to the internet as a critical practice and theory at once: It means to insist on our vision of a feminist internet as a technopolitical and a collective way of becoming that we can 'co-create' and that involves bodies, materialities, networking skills and technological knowledges.

One of the ways in which this technopolitical becoming materializes is through the practices of feminist servers such as Systerserver, which is the feminist server that channels some of our more current technofeminist practices. Systerserver is one of the oldest feminist servers, founded in 2005 in the context of the Gender Changer Academy and the Ecelectic Tech Carnival. (more on that?) As part of Systerserver we are well connected and co-dependent on other feminist server projects (anarchaserver, Maadix, leverburns, digiticalcare...) and autonomous tech collectives. Together we have a need to share ways of doing, tools & strategies to overcome/overthrow the monocultural, centralized oligopolic surveillance & technologies of control. We need to resist the matrix of domination. Stop the techno-facilitated exploitation and continuation of social and climatological injustice(s).

A network of one's own

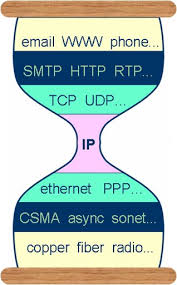

A feminist server is not just a technically facilitated node on the network, it is a place on the internet that we can inhabit and share with our intersectional, queer and feminist communities: A place where our data is hosted, the contents of our websites, where we are chatting, storing our stories and imaginaries and access the multiple online services we need to get organized (mailing lists, calendars, notes,...). This sense of a networked locality, of having an address which can be visited on the internet, is facilitated by the internet protocol (IP) which -- amongst other requirements -- allows a computer to become an addressable node. (Footnote: Servers are computers on a network, so called nodes, who are answering to the calls of nodes, that is to say to other computers on the network. These other computers take on the role of clients making calls such as the call to view a website, to provide a document, to send an email or to receive a video stream.)

However, serving, and becoming a server is not just a technicality or a neutral relation between two or more computers. It is a technopolitical practice, that is tied to politics of protocols, of infrastructure, power, responsablility, dependencies, labour, knowledge, control, etc. What are the politics of having an IP address, of being addressable on the internet? How can we subvert our dependencies on commerical services?

Who can become a server, who is being served? [x]

As feminist servers, we refuse to be served in ways that increases our dependencies on cis male dominated and commercial technologies and the hegemonic technical paradigm around individualism and commerce. The spacial vocabulary around having a place or 'a room of one's own' on the internet is an important principle that communicates the politics of feminist servers in serveral ways, referencing feminist struggles for independence and safe/r off- and online spaces.

One of its meanings is taking up the feminist writing by Virginia Woolf from 1927. In her essays, Woolf addresses the need for women to escape from societal pressures of fulfilling their socially assigned roles as care-givers, house wives, servants. For many people in the feminist movement, the fight to become our own persons, with our own spaces, our own devices and ways of accessing the internet, is still ongoing in the face of intersecting, economic oppression and societal roles and burdens. This can sometimes look like a practice of withdrawal, of temporary locking the door behind oneself or of creating separatist spaces with peers whose experiences are similar to our own.

Yet importantly, insisting in this room of one's own-- not unlike the room of the woman who writes on the back of and in reference to other women authors (a room full of book one can presume) -- is also of connecting with others, of making critical connections.

In terms of feminist servers, the server thus becomes a 'connected room' or even 'infrastructures of one's own' characterized by the tension between the need for self-determination and the promiscuous and contagious practices of networking and making contact with others. These practices inherently surpass strong notions of an identitarian 'self' in a collective and heterogenous search for empowerment and are taking part in creating the conditions for networked socialities and solidarities. (see Femke, in Ongoingness)

A connected room, network of one's own, with allies as co-dependencies, attributes collectivities interacting as radical references which evades hierarchies of cognitive capital based on individuals and underlines the collective efforts to resist within the hegemonic technological paradigm.

Furthermore, the metaphor of the room highlights the ways in which bodies need to be accommodated in the practices of feminist networking.

"We think of a feminist server as an (online) space that we need to inhabit with our bodies. As inhabitants, we contribute by nurturing a safe space and a place for creativity, experimentation and justice, a place for hacking hetero normative and patriarchal technologies. " (quote Ongoingness?)

These bodies incorporate our data bodies but also the ways in which we show up in gatherings and places outside of digital networks. Self-organized gatherings such as the ecclectic tech carnival or the trans hack feminist convergence, as well as residencies or other feminist server meetings have been crucially informing and nuturing feminist server and networking practices since the very beginning.

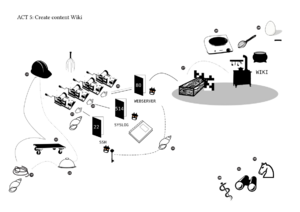

The importance of offline-online entanglements can also be demonstrated by the attempt to provide a physical interface of Anarchaserver, a feminist server project which was started in 20xx and which is currently dormant. The public interface of the server was created as a room onsite an anarchist commune in the mountains by Barcelona that could be visited and which was structured according to the functionalities of its hardware-software counterpart (including a repository... and even a firewall, https://zoiahorn.anarchaserver.org/physical-process/). Another example is the performative event 'Are you being served?' developed by ooooo which took place during The Feminist Server Summit, organized by constantvzw in brussels https://areyoubeingserved.constantvzw.org/Home_server.xhtml Home is a Server is about mimicking computer functioning through human energy and towards a human goal (eating the pancake instead of just publishing its recipe online), transforming ourselves into CPU, data, kernel, hard drive, booting, rebooting, getting into Kernel Panick and finally managing to get through the difficulties of sending data out, making a wiki that eventually achieves the very physical process of making pancakes for the group during the afternoon, 12–15 December 2013

((Instead we need a room of our own and we need a ‘connected room’ of our own.* or a network of one's own [3] [4]))

((A connected room, network of one's own, with allies as co-dependencies, attributes collectivities interacting as radical references which evades hierarchies of cognitive capital based on individuals and underlines the collective efforts to resist within the hegemonic technological paradigm. [5]))

Data literacy: The knowledge about networks and their politics

Networking is a practice that involves knowledges about networks as well as the technopolitics that are tied to different ways of connecting, of making space and relating to online services.

One way of addressing the politics of networking and of relating with technology is by 'following the data'. Data is not just an informational unit or a technicality, it is how we relate to computers, both on a supra- or infra-individual level but also as something that can be be incredibly personal and intimate. We need to keep asking 'Where is the data?'

Besides from these roles we need to encourage “data infrastructure literacy” for the ability to account for, intervene around and participate in the wider socio-technical infrastructures in which data is created, stored and analyzed. Our intent is to make space for collective inquiry, experimentation, imagination and intervention around data. Data as in binary information, suitable for processing by computers, recognizing it's intrinsic (human)labour conditions, maintenance and hence care. In becoming more literate, we cultivate our sensibilities around data politics and as well engage a wider public with digital data infrastructures. [6]

For this reason we need to make servers visible and physical as a crucial/critical space,

By making infrastructures visible with the aid of drawings, diagrams, manuals, metaphors, performances, gatherings, systerserver traverses technical knowledge with an aim to de-cloud (Hilfling Ritasdatter, Gansing, 2024) our data, and redistribute our networks of machines and humans/species.

politics of networks

Being part of the Internet, or internets, creating and maintaing our own networked infrastructures involves an understanding of the technicalities and politics of IP address, local, public, private and virtual networks, routing and subnetting, an economy of scarcity, institutional and corporate control. Systerserver infrastructure is sheltered in the data room of mur.at, a cultural association which enables the hosting of a wide variety of art and cultural initiatives in a (shared) virtual server, along with Systerserver’s two physical servers. Donna Meltzer and Gaba from Systerserver went to install the most recent hardware in 2019 . The server is called Adele. The older machine was installed and configured in 2005 and is called Jean. Both are running on Debian, which is a Linux based operating system, with different services on each machine. Jean hosts a social network platform, a mastodon instance for our wider feminist communities, and tinc, a VPN software. Mastodon is a free and open-source software for microblogging. It operates within a federated network of independently managed servers that communicate using the ActivityPub protocol, allowing users to interact across different instances within the Fediverse. Tinc is a VPN tunneling software. It creates virtual private network(s), enabling computers and machines to connect to each other, even if these machines are not servers with a public address. The network is hidden, thus called private, as it only exists between the machines that are added to it.

A VPN can also facilitate as a public entry point to these machines, allowing them to become servers. So if a request is made to a domain name, which e.g, is serving a wiki, hosted in one of these machines hidden within the private network of Jean, the domain name request is first reaching Jean, the only public address in this network. On Jean, a web engine configuration software is resolving the domain and mapping it to the private address of the machine, which hosts the wiki. The request is thus rerouted internally, meaning inside the hidden network to the specific machine.

Systersever has configured three of these private networks, distinguishing between "internes" and "alliances". The first is for Systerserver physical servers in mur.at to reach a backup server in Antwerp, which has no public address. The latter is for facilitating a range of home based server initiatives within our community, e.g, the etherpad servers of leverburns which we use for technical documentation during our server maintenance worksessions. Or allied communities, e.g, Caladona that want to serve content without having to commit to the high costs of acquiring a public address. There is also the network named “systerserver” which was our first attempt to install and configure Tinc for the publishing infrastructure of the ServPub project, making the raspberry-pies wiki and website accessible as servers. Home based servers are assigned with dynamic addresses that change periodically. A home router switches its public IP regularly, thus called dynamic IP addresses, because the internet service provider (ISP) temporarily assigns an IP address from a given pool, called also a lease time, that can expire and trigger an IP address change. They do this to manage their available addresses more efficiently and for minor security benefits. The drawback of this, is that a home router cannot be assigned a domain name, since domain names need to be mapped to what we call a static of fixed IP address in order to be translatable to a unique machine’s service or content.

Hence for home based servers to be accessible in the Internet they need a static IP address. With the creation of the Tinc networks, as we mentioned above, home based machines can become servers since they can be accessed via the IP of jean which has a fixed IP, assigned by the networking of mur.at. Tinc (and other VPN) tunnels operate within private networks, usually in the ranges of 10.0.0.0 pool, and the machines 'invited' inside these tunnels can connect to each other. The machine with the public IP, or the public node, as we call it within the private network, provides the web engine configutation software – nginx, apache being the most popular and FLOSS options, and those that we work with in Systerserver infrastructure – for forwarding traffic requests, which is also called a reverse proxy. Proxy because Jean servers as the proxy to reach a hidden (private) machine, and reverse, because the hidden machine can respond back to the request by serving its content to the computer who requested it. This is therefore the other distinct feature of a server, the ability to receive and send data over the network, while a computer who is not serving, known as the client, and which is the typical case of working with our computers from home, browsing the internet, and being able to request content, but not being allowed from our home router to send or serve content outside our home network.

A VPN software and a reverse proxy configuration is a tactical dependency to avoid the costs for a static IP address, therefore overcoming the shortage of IPv4. Or to avoid censorship and institutional control over the content of a server, since it remains hidden from the public network provided by the ISP. [7] It also facilitates the mobility of home based servers, and reinforcing trusted networks by enabling hidden localities – the actual IP address of the private server is not known, but to the public node. Who is the public node, hence becomes a political dependency. And the legalities that govern that said public node become crucial depending on the content being served. We have to keep in mind that adding new servers to our Tinc network(s), requires more bandwidth traffic, and hence material resources from the dataroom in mur.at.

choose your dependencies

An alternative for when your ISP changes your home network's IP address, would be Dynamic DNS, which is a useful service that allows you also to use a fixed and memorable address for your home network. You can often set up DDNS on your router. You can also run a DDNS client on one of your servers.

/// needs more... / generalisation + references

THIS SEEMS MORE INFORMATIVE /MAYBE IN SEORATE DESIGN STYLE

lan/wan/van

To understand somehow more the private and public IP’s and networks, we can look at them from their naming conventions. LAN is an abbreviation for LOCAL AREA NETWORK, and the reserved addresses for these networks are either 192.x.x.x, 169.x.x.x (DHCP) and 172.x.x.x. These addresses are distributed within one room, building that has a router. The router that broadcasts the WiFi or provides ethernet cable connections is the interface between the local network inside the room, and the WAN (WIDER ARE NETWORK), basically the Internet.

The addresses 10.x.x.x are reserved for the private networks, that are also called virtual. Since Virtual Private Networks are more complex to comprehend. Let's introduce a little bit of their history, hoping that it will illustrate their purposes and functions more.

regulatory bodies ICAN-RFC's develop/discuss standards (missing)

routing / subnetting (missing)

history and topology of VPN

After the WWW and http protocol, the question of secure connections became urgent as the ability to connect beyond institutional networks became wider. AT&T Bell Laboratories developed an IP Encryption Protocol (SwIPe), implementing encryption in the IP layer. This innovation had a significant influence on the development of IPsec, an encryption protocol that remains in widespread use today.

"IPsec, introduced around the mid-1990s, provided end-to-end security at the IP layer, authenticating and encrypting each IP packet in data traffic. Notably, IPsec was compatible with IPv4 and later incorporated as a core component of IPv6. This technology set the stage for modern VPN methodologies." [8]

By end of 90s Microsoft worked towards implementing a secure tunnel protocol, creating a virtual data tunnel to ensure more secure data transmission over the web. The encryption methods used in the PPPP was vulnerable to advanced cryptographic attacks. the MPPE (Microsoft Point-to-Point Encryption), only offers up to 128-bit keys which have been deemed insufficient for protecting against advanced threats. Later together with Cisco, they developed another protocol, the L2TP, for serving multiple types of internet traffic.

"L2TP (Layer 2 Tunneling Protocol) works by encapsulating data packets within a tunnel over a network. Since the protocol does not inherently encrypt data, it relies on IPsec (Internet Protocol Security) for confidentiality, integrity, and authentication of the data packets traversing the tunnel." [9]

A later tunneling protocol is the openVPN, which has been designed as a more flexible protocol allowing port configuration, and more security.

Tinc protocol follows here...

the drawing of encapsulation from tunnel up/down

While https is another way to secure traffic over the internet, it is distingue from IPSec in that IPsec secures all data traffic within an IP network, suitable for site-to-site connectivity. HTTPS, the secure version of HTTP, using SSL, and its successor TLS secures individual web sessions, typically used for secure remote access to specific applications via the internet.

geolocation and network infrastructures

Now that hopefully we have a clearer idea of the local/private networks vs the public networks aka Internet, it’s important to dive into the distribution of addresses and the politics that stem from this. According an online article about the state of the Internet as of 2023, several factors have contributed to the decline in IPv4:

• Market Saturation: The Internet may have reached a point where there is no additional demand to drive further growth, leading to a natural plateau in IPv4 usage.

• Shift to Content Distribution Networks (CDNs): The transition to CDNs for digital services has reduced the demand for traditional content distribution methods, impacting IPv4 growth.

• IPv4 Address Exhaustion: The depletion of available IPv4 addresses has led to the adoption of address-sharing technologies and significant architectural changes in Internet services, further contributing to the decline.

Despite these trends, the article notes that the majority of the Internet user base (slightly under two-thirds as of the end of 2022) still relies exclusively on IPv4. The future trajectory of IPv4 and IPv6 usage remains uncertain, influenced by technical developments, economic factors, and global events, such as pandemics, economic crises and communications technology in different parts of the word. IPv6 adoption is scant in most of Africa, the Middle East, Eastern and Southern Europe, and the western part of Latin America. Due to the market saturation and the smaller pace of network growth (double check) in those regions appears, for the moment, be adequately accommodated in the continued use of IPv4 NATs. This means that ISP can charge higher prices for a declined number of IPv4 and the need for self or community based hosting that relies on static and fixed IPv4s can be obtained through VPN tunnels and reverse proxies, or Tor onions. [10]

During the translation of the manuals Tunnel Up/ Tunnel Down, the Chinese artist and translator Biyi Wen pointed us to the art research project A Tour of Suspended Handshakes, in which artist Cheng Guo physically visits nodes of China’s Great Firewall. Using network diagnostic tools, he identifies the geolocations mapped to IP addresses of these critical gateways, based on data published by other researchers. At times, these geolocations correspond to scientific and academic centers, which seem like plausible sites for gateway infrastructure. Other times, they lead to desolate locations with no apparent technological presence. While Guo acknowledges that some gateways may be hidden or disguised—for example, antennas camouflaged as lamp posts—the primary reason for these discrepancies lies in the redistribution and subnetting of IP addresses, as well as their resale. These factors make it difficult to pinpoint exact geographical locations. Additionally, online IP location tools provide coordinates in the WGS-84 system (the global GPS standard), whereas locations in China must be converted to GCJ-02 (an encrypted Chinese standard). This further complicates geographic identification, as mapping activities have been illegal in mainland China since 2002. In the case of the Great Firewall, the combination of IP redistribution and encrypted coordinates obscures the true locations of its gateways, rendering the firewall a nebulous and elusive system. Similarly, for mobile (ambulant) servers, geolocating individual servers—beyond the main public-facing ones—remains a challenge. However, unlike the Great Firewall, the mobility of such servers is not enforced through top-down government control. This decentralization has the potential to counteract centralized policies and provide a means of circumvention. [11]

resources matter

traffic costs and electricity (missing)

index.php?title=Category:ServPub

- ↑ https://digitalcare.noho.st/pad/p/servpub

- ↑ https://eth.leverburns.blue/p/servpub-2b

- ↑ (Spideralex) https://creatingcommons.zhdk.ch/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Transcript-Femkespider.pdf.

- ↑ referring to the paranodal periodic publication and series of events and worksessions in rotterdam revisting of Virgina Woolf's classic essay.

- ↑ https://www.roots-routes.org/hacking-maintenance-with-care-reflections-on-the-self-administered-survival-of-digital-solidarity-networks-by-erica-gargaglione/

- ↑ https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2053951718786316

- ↑ See also the networking introduction of the art project A Traversal Network of Feminist Servers, which allowed rosa, the project's mobile server to travel to places: the Hub, p.9, accessed on 24 July 2025, https://atnofs.constantvzw.org/ATNOFS-screen.pdf. However systerserver as a techno-feminist collective don't prescribe to the idea of originality and individuals' accreditation to technicalities that have a long history of software development and implementations in various contextes, we cite the reference as another example of using VPN in artistic infrastructural practice.

- ↑ https://www.paloaltonetworks.com/cyberpedia/history-of-vpn

- ↑ https://www.paloaltonetworks.com/cyberpedia/what-is-l2tp

- ↑ https://blog.apnic.net/2024/01/09/measuring-bgp-in-2023-have-we-reached-peak-ipv4/

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Restrictions_on_geographic_data_in_China