<unicode> ‡ ※ ☛ </unicode>

Whereas a book would usually end with a ‘list of references’ or 'works cited', this book’s final chapter concerns the practice of ‘referencing’ – the reference as a verb and not a noun. This change of perspective underlines how the creation of references, configurations of authorship, indexing of knowledge, and other scholarly activities – that are usually considered mundane and less important than the actual knowledge itself – are in fact an intrinsic and important part of the constitution of knowledge: What we know cannot be separated from the formats of knowing. To use another word, academic referencing is part of creating what Celia Lury has referred to as an ‘epistemic infrastructure’ – the organisational structures and facilities by which knowledge becomes knowledge. Like other formal cultural expressions, also academic referencing follows formal properties of circulation, composed and upheld by technical infrastructures with specific features.[1]

As also mentioned in the introduction, ServPub explores self-hosting as an infrastructural practice, the potential for autonomy in the publishing process, and not least the role of communities in this. Referencing is to be seen in the same perspective – as an exploration of the potential for social and technical autonomy in the process of making knowledge, knowledge.

Referencing is part of a constellation of practices such as quoting, indexing, paraphrasing, annotating, writing footnotes, selecting, etc. Inherently, they can take many forms and do not necessarily work together. For instance, if we write an email to a friend saying, “my neighbour told me the traffic has dramatically increased in the street these last two years”, We are quoting and referencing. But we are not making my reference explicit (we are not naming our neighbour) and we do not index our reference. Academic publishing, in turn, establishes fixed and formal procedures to quote, index, annotate, etc. What are the logics of referencing and formatting knowledge in academic publishing – considering social, technical, epistemic or other forms of autonomy?

Radical referencing

A reoccurring term in the collective process has been ‘radical referencing’. The notion was brought up by Systerserver in a collective conversation on how, what and who to reference in the making of this book; that is, in our collective practice of referencing:

within systerserver we started to introduce the concept of radical referencing -- as a feminist strategy to share knowledges. Radical referencing came to us after a meeting with an artist, publisher and performer we know for years A.Frei, nowadays called https://aiofrei.net/. aio frei is a non-binary sound artist, relational listener, sonic community organizer, collaborator, sonic researcher, record store co-operator, graphic designer, experimental dj and mushroom enthusiast based in zürich.[2]

As explained, the making of references is partly inspired by a real-life social encounter (in a bar at an event) and is therefore also situated, embodied, and even non-verbal. However, the further investigation of the term ‘radical reference’ also leads to a distributed collective of library workers in the United States, ‘Radical Reference (RR)’.[3] An important task in librarianship is to seek and make available information, a process deeply dependent on the existence of catalogues; that is, an infrastructure of references, indexes and data. Many of the formal requirements in referencing (i.e., the stating of authors, publishers, years of publication in the correct manner) simply come from the need to build and maintain an infrastructure where one can identify and access publications.

RR questions the existing infrastructure from an activist perspective. They argue that the librarian is both a professional and a citizen, who has come to realize the activist potential of their profession. As librarians Melissa Morrone and Lia Friedman put it “RR rejects a ‘neutral’ stance and the commercialization of data and information, works towards equality of access to information services,” and therefore actively seek to form coalitions with activist groups.[4] RR is by no means a new thing. Members of the American Library Association (ALA) also took part in the ‘Freedom Libraries’ in the 1960ies, addressing the racist based inequities in American library services.[5] In the time of its existence, RR would assist journalists and the public in anything from finding information on the radical right on college campuses[6] to providing references on cycling in London.[7] In this sense, ‘the library’ is not just a building with shelves, but potentially everywhere.[8]

What has appealed to many of the participants in the writing of this book, and sharing the notion of ‘radical referencing’ as a working principle, is this idea of a wider and living library of references. There is a collective interest in situations where references are not always identifiable as objects of knowledge suitable for a conventional library (ascribed an International Standard Book Number (ISBN) or a Digital Object Identifier (DOI), for instance) – let alone listed at the end of a book. This would, for instance, include the practices of activists and others, who are not always considered ‘proper references’ in academic writing, and where the formal standards (or ‘styles’) of references can be hard to meet because the knowledge relies on collective efforts (such as workshops, social gatherings, and conversations) or is dynamic in nature (preserved in a wiki, or other technical system).

To some, there is also an appeal in the recognition of the librarian’s labour as an activist; or perhaps rather, the activist as a librarian. RR resembles other library projects found in grass-roots software culture, where it is common (also to the authors of this book) to use Calibre software to access and build ‘shadow libraries’.[9] That is, for hackers and activists to become their own ‘amateur librarians’, building and sharing catalogues of publications – not only to distribute knowledge, but also to curate knowledge on particular subjects, and to preserve knowledge prone to erasure or other types of discrimination. Proper referencing here becomes a question of care and maintenance of an epistemic infrastructure, such as a catalogue or an index of references at the end of a book, in the pursuit of autonomy.

In the following, we take these appeals as points of departure for an exploration of the logic of referencing, and the potential implications for autonomous academic referencing.[10] In other words, if referencing is a compulsory formality in the publication of research, we ask what purposes, and whose, does this formality serve? Referencing in a radical perspective is not just a matter of autonomy from certain references, or types of referencing (like the formal academic one), but rather an examination of the condition of all referencing, and potentially also an exploration of the forms that a liberation from referencing would potentially take – in recognition of other collectivities than the one that occur in a, say, a research community (connected by a network of references), and also in recognition of the various technical infrastructures (such as the MediaWiki or Etherpads used for collective writing) that make referencing in the ServPub community possible in the first place.

Academic akribeia and citation styles

Writing culture extends more than 4,000 years and making reference to other manuscripts has always been practiced. For instance, Aristotle would often reference his mentor, Plato, but as scholar of Ancient Greek, Williams Rhys Roberts has argued: “The opening chapters of the Rhetoric do not give Plato's name, but I wish to suggest that they contain some verbal echoes of his Gorgias which are meant to be ‘vocal to the wise.’”[11] Referencing does not inherently involve a direct mention of a name, and the study of ancient texts involves much debate on these intertextual relations. Until the 19th century there was no need to specify the ways in which one speaks of others. As readers of scholarly articles will know, there are nowadays set traditions of references that all authors will need to abide by, formulated as ‘styles’ of referencing. The organization of citing, listing, and other tasks finds, in other words, its form in a pre-defined template. This template is much more than a mere formality and belongs to an academic history of knowledge governance and an intellectual history of epistemic infrastructuring.

One widely used standard for referencing within the arts and humanities is the American Modern Language Association’s standard, the MLA format. MLA, along with several other standards like the Association for Computing Machinery’s (ACM format) or the American Psychological Association (APA format), indicates that the act of referencing belongs to an institutional practice of ‘scholarly’ work and academic akribeia; that is, a rigorous keeping to the letter of the law of the institution (and not just its principles).[12] With a certain ethical – or even religious – undertone (‘the right way’), it performs as a marker of ‘proper’ knowledge within a particular field of knowledge, serving to demarcate it, exactly, as a field of knowledge. The Modern Language Association was, for instance, founded in the late 19th century when programs in language and literature were being established at universities to promote and preserve a national cultural heritage and identity. Formatting references was a way for librarians to index reliable and useful knowledge in a field, and to provide insights into a network of scholars referencing each other, as well as into what and whose knowledge mattered the most. Such practices of demarcation and impact cannot be separated from the governance of research and are no less important in today’s austerity measures of knowledge production.

Besides librarians (as mentioned above) and academic associations, also publishers were keen to build epistemic infrastructures for referencing. The Chicago Manual of Style(used in this book) was historically the first attempt to specify clear principles for making references – quoting in a text, and listing the works quoted. It was first invented by the University of Chicago Press in the late 19th century to streamline the work of editors who had to produce books out of handwritten manuscripts and therefore drew up a style sheet and shared it in the university community.[13] Over time, it has become one of the most widely used reference guides for writers, editors, and proofreaders. It comes in two versions: The “notes and bibliography” where sources are cited in numbered footnotes or endnotes, and the “author-date” where sources are referenced briefly in a parenthesis that can be matched up with the full biographical information in a concluding reference list. As we will discuss later in this chapter, a practice of making footnotes, and also of ‘bracketing’ references are more than anything a particular cultural practice that has become naturalized within an academic publishing world, but it also comes with particular histories and assumptions that reflect hierarchies of power, knowledge and knowledge production. For, after all, what is a reference? And under what terms and conditions does an academic reference and authority occur?

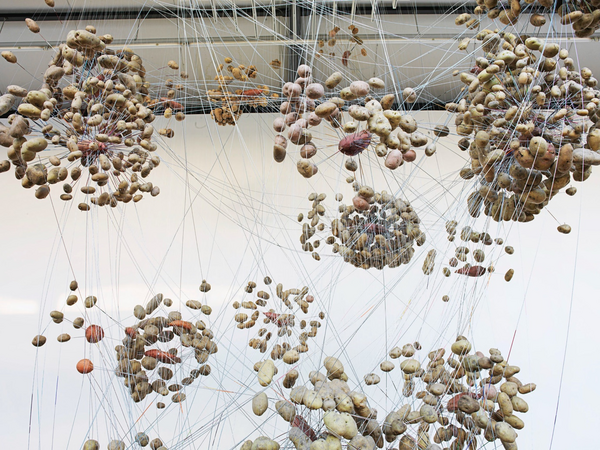

As an illustrative example, The Works, Typologies and Capacities by Dutch artist Jeanne van Heeswijck uses 26 different types of potatoes to visualize all the collaborations and projects undertaken by Van Heeswijk from 2001 to 2019. The installation is divided into 26 typologies with 26 specific capacities, each linked to a potato species. Consider, for example, the artist who contributes to a work or a project, but also the activist, the teacher, the cameraman, the sound man, the reporter, the curator, the musician, the actor, and so on. The choice of different potato varieties as materials symbolises those typologies and capacities in a network.

Authorship and research ethics

‘Potato style referencing’ does not yet exist in scholarly akribeia. Instead, there is an obsession with origin in a different sense: knowledge has to come from someone, somewhere, sometime. The typical bibliography encodes limited entities: time in the form of dates, spaces in the form of locations (sometimes), people or collectives of people in the form of names, organisations in the form of publishers. Here the figure of the author, treated as a self-contained unit, plays the most central role. The scope is much broader than merely establishing ‘the letters of the law’ (to cite the formally correct way); it has to do with a more idealistic research ethics. Establishing authorship is a question of acknowledging the origins of knowledge, but it is also a scientific community’s promise of holding people accountable for knowledge, and for guaranteeing the validity of that knowledge: at all times, knowledge must be ready to be verified by others, and authors must be prepared to accept contradiction.

This type of research ethics was the topic of the acclaimed ‘Vancouver Convention’ in 1978, where a group of medical journal editors decided to establish a rule of conduct for scientists, editors and publishers, known as the ‘Vancouver Guidelines’.[14] Although these ethics standards were developed within the medical sciences, they have been applied within all the sciences, and also the arts and humanities. But are they easily applicable in a book such as the one you are reading now?

The Vancouver guidelines outline four criteria, by which all listed authors must abide.[15]

- An author is someone who has made a substantial contribution to the work.

- An author must have reviewed the work.

- An author must have approved the work.

- An author is accountable for the work.

These ethical standards clearly bring a level of order to academia (letters of law to abide by), but a critique often raised is that they do not sufficiently consider the extent to which authorship, and making reference to authorship, are situated within cultural communities of practices.[16] In some types of knowledge production, like particle physics, for instance, it will make perfectly good sense to include hundreds of authors who have all contributed with specific tasks, but who cannot all possibly have read the final proved version and therefore be held accountable. In other research traditions you would credit people who cannot read, like in some areas of social anthropology, acknowledging the productive role of local informants. In interdisciplinary research, an author within one field may have read and approved a section contributed by a researcher within another field, but with no authority to determine the validity of the knowledge.

In other words, even in the established world of research writing and research publication, the question of where an author is, and who speaks in a text, poses challenges. The complexity of enunciation points to a different type of research ethics, where one is less concerned with the validity and verification of the content, and more with the ethics of textual production itself; that is, an attention to the often unorganized patchwork that knowledge sharing is and becomes in a text (including the writing of this one). As once pointed out by Roland Barthes, text functions as textile:

“a multi-dimensional space in which a variety of writings, none of them original, blend and clash. The text is a tissue of quotations drawn from the innumerable centres of culture.”[17]

Not only in literary writing, but also in research writing, one might argue that language does not always refer to some-thing, but – in the extreme – also to a commonality, something shared; a set of conditions for common ground where the question of ownership and authority remains undefined, where meanings swerve, and new sensibilities and habits arise.[18] In similar ways, the stipulated originality in science and research (‘The Vancouver Guidelines’) is partly refuted in this publication; the wiki4print is not only a repository tool for print but contributes to a larger whole and network of voices. No authorial voice can be raised fully; rather, it is a chorus of collective voices that takes on a name – ‘Systerserver’, 'NoNames', ‘Ingid’, ‘ServPub’, ‘SHAPE’ – in full recognition of the wider ‘tissue’ of a culture’s immeasurable voices of people and collectives (including Martino Morandi's work wiki-to-pdfenvironments (TITiPI), Constant and Open Source Publishing's (OSP) work on web-to-print, and much more, mentioned in this book).

The demonic grounds for referencing

As we have seen, scholarly akribeia is connected to the assignation of an origin which takes the form of the author’s figure to assess who is speaking as well as for verification. Rather than a fully coherent technique, this form of referencing falls short of accounting for the academic contexts in which knowledge is produced and cannot grasp the ‘textile’ dimension of discursive production. This has even stronger implications for those who produce knowledge outside of academia and those whose knowledge has been historically erased or appropriated. Indeed, referencing’s epistemic dimension cannot be separated from a larger problem of symbolic capital production. It is a key instrument in an economy of visibility central to the contemporary knowledge factory and a vector of exclusion of the subjects that are not deemed good ‘referents’.

In that perspective, scholarly akribeia needs to be challenged on a political ground as well. Katherine McKittrick’s discussion of Sara Ahmed’s intervention in the politics of referencing gives a sense of both the urgency of interventions and their complexity. In her book Living a Feminist Life, Ahmed adopts a citation policy that excludes white men. To absent white men from citations and bibliographies opens up a space for the inclusion of other scholars. It simultaneously emphasizes the pervasive reproduction of a gendered and racial canon by contrast. What is naturalized under the routine referencing of the same canonical authors as a useful procedure for attribution is revealed as a conduit for white patriarchal authority.

In her ‘Footnotes essay’, McKittrick acknowledges the “smartness” of Ahmed’s proposal but problematizes it further. Is it enough to simply replace some names by others, leaving the structure intact? And “Do we unlearn whom we do not cite?”[19] McKittrick’s proposal is that we “stay with the trouble” of referencing, and that we suspend the urge to make the cut. Writing should acknowledge its unstable foundation on demonic grounds:

“the demonic invites a slightly different conceptual pathway—while retaining its supernatural etymology—and acts to identify a system (social, geographic, technological) that can only unfold and produce an outcome if uncertainty, or (dis)organization, or something supernaturally demonic, is integral to the methodology.”[20]

The reason for this goes beyond a mere post-structuralist stance. An insisting question needs answering: what kinds of collectives are implied and elicited by different forms of referencing? How to relate and do justice to the kinds of collective attachments and entanglements that cannot be resolved by assigning a name? How to balance the generosity and necessity of acknowledging, expressing, nurturing one’s relations and resisting at the same time the form of interpellation that is inherent to the naming, the assignation? How to acknowledge one’s debt without any simple recourse to ‘credit’? There isn’t really one satisfying answer to these questions. In part, because there is a form of recursivity to citational practice that tries to do justice with the various levels of agency involved in a creative process. As ooooo (who is part of Systerserver and the making of this book) observed in a commentary to this text, spaces have their role to play in bringing up ideas together:

“we wanna insist on including social environments, (self-organized) gatherings of peer-to-peer sharing as 'identifiers’. The place where you were introduced to the specific author, situate it.”

Specific examples from this book would include for instance, In-grid's poem, which opens the servpub page landing page, stressing how social and technical forms and organisational processes come together in referencing:[21]

Why Wiki4Print?

2+to=4/for to from Varia's wiki-to-print[22]

2 from Hackers and Designers wiki2print[23]

4 as it is what the wiki is for

for as it is the fourth iteration since TITiPI's wiki2pdf[24]

The book is made with Wiki4Print techniques, but wiki4Print as a platform does not occur without wiki-to-print developed by Creative Crowds' participation in the project, which – as they describe it – is “a collective publishing environment based on MediaWiki software, Paged Media CSS techniques and the JavaScript library Paged.js, which renders a preview of the PDF in the browser.”[25] Nor would it be possible without the collective Hackers and Designers and The Institute for Technology in the Public Interest (TITiPI). The poem’s hyper-links stress the collective efforts to build a network of practice and practitioners, but the poetic language itself also underscores how language is more than an exchange of information. Poetic language tends to make us aware of a shared set of conditions in language – the grounds on which we speak.

These infrastructural inspirations and contributions are "situating" (as described by ooooo) other groups and individual efforts within the project. The ongoing documentation of the tools and services used during the construction of the book not only works as a repository of technical knowledge, but also as a referencing tool for making visible the groups and projects that developed the infrastructure on which Servpub iterates (including, for instance, XPub's "tinc"), as well as the active practices that ultimately allowed the construction of the book (e.g. internal communication using and managing "tinc").[26]

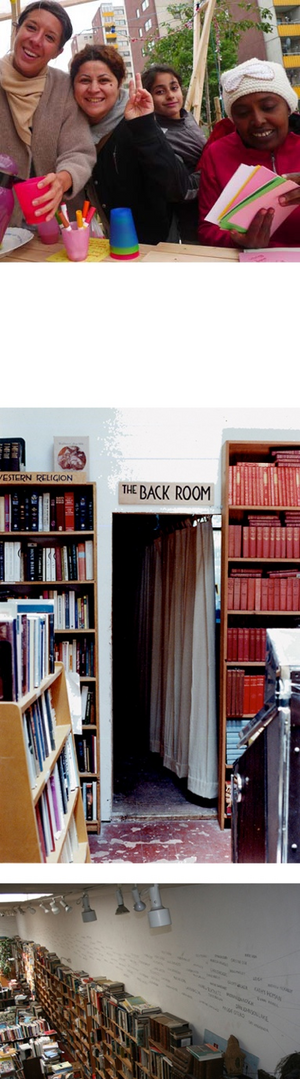

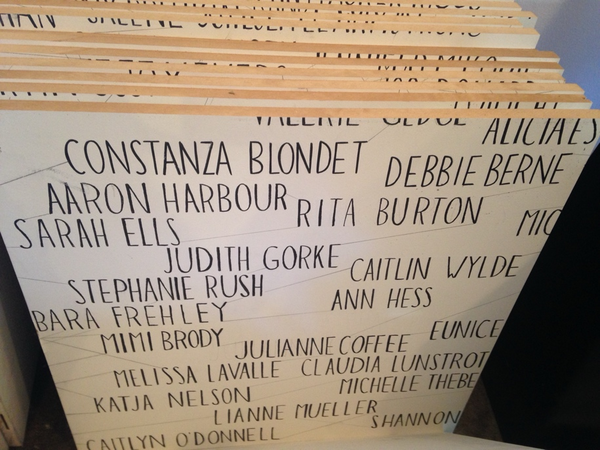

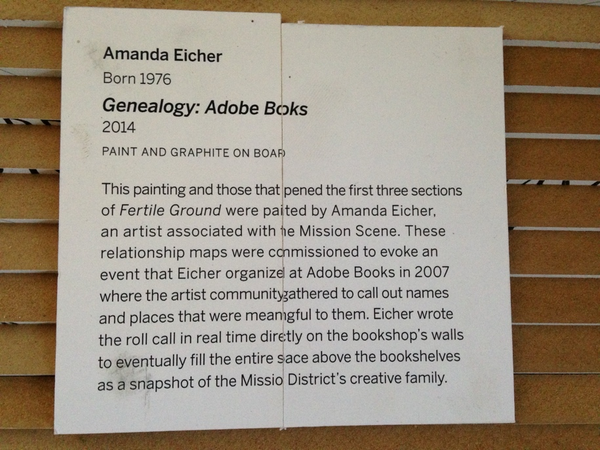

As ooooo further suggests, the quality of encounters is significantly defined by the surroundings and atmospheres. But, as they also point out, spaces are managed, sustained, and inhabited by people. Such referential dimensions of the space of encounter is visible in the practice of Amanda Jeicher, as ooooo remarks:

“In the Adobe bookshop, the artist Amanda Jeicher started keeping track of 'readers', visitors of the local community. On the last images of the scroll (fig. 1) you see the implementation in the bookshop which was also a gathering place for reading and activities. She later when the bookshop was closing made an artwork with the documentation of the real-time roll call of names and people who were meaningful to local artist and communities (fig 2, 3).”

Each reference brings in a new entanglement. Which begs the question: where does referentiality end?

Another complicating factor is that any answer is context-specific. A strategy that works in the citational economy of academia might simply fall flat in an activist context where fluctuating forms of presence are integral to a practice. Not to mention the problem of networks of collaboration that straddle different worlds with their different citational practices. This publication is a good example of this conundrum. We opted to attach all our names to the publication as a whole rather than by chapters. We aim to emphasize the collective nature of the effort. Indeed, if we didn’t all write actual words in every chapter, all chapters are the results in some form of a collective discussion and inspiration. There is a kind of diffused authorship that permeates the publication. Nevertheless, we belong to varying degrees to worlds where citational practices are part of an economy of visibility. Therefore, we still attach our names to the publication. This form of balance is an attempt to engage with the collective who worked on this manuscript whilst acknowledging our dependencies on modes of production such as academia and building one’s CV. The part where a name points to a delimited and singular, well-bound entity. But when it comes to the demonic ground (the unstable foundation for writing this text and this book), what kind of practices do we mobilize? Before we get back to this question, we must introduce another set of agents weaving the tissue of references: the machines, networks and protocols underlying the ServPub collective.

ServPub as a technical referencing ecology

To summarize, the exploration of the logics of referencing, in an autonomous perspective, implies a questioning of the authority of the text. When referencing, there are debts with credits, but also more demonic ones, without credit – exceeding the restricted economy of exchange found in academic conventions of referencing (such as the Vancouver Guidelines).[27] However, this is only a partial answer. Textual authority cannot be excluded from the technical systems, intrinsic to the epistemic infrastructure of referencing. Referencing of text is maintained not only by authors, librarians, editors and publishers, but also by a range of software products, such as Endnote or Zotero – automating and reassuring the indexicality of the text, that quotations are formatted, their origins identifiable in the larger repositories of text, and that they are listed correctly; keeping the ledger and minimizing the risk of debts without credits, so to speak. But when it comes to the demonic ground of a text, what kind of socio-technical practices do we then mobilize?

This ‘book’ is not only printed material, but it also exists in a technical layering, or what N. Katherine Hayles would call ‘postprint’. Unlike previous publishing infrastructures, the subreptitious ’code’ of the book positions it as a product of its technical epoch and modifies its nature.[28] This is evident in the content and skeleton of this project, where the book exists in a series of technical and social infrastructures, that afford different materialities (the server, the wiki, the html code, the pad), but it is also reflected in the social practices related to these materials. As an immediate example, Hayles foregrounds the XML code used in her own book: the code enables the cognitive assemblage of humans and machines to function by enabling communication between them.

The practice of referencing within this book is explicitly embedded in a technical ecology in a relatively traditional way, where for example a bibliography generated within Zotero both enacts the spirit of openness while encoding the information in a suitable ‘Vancouver-complying’ standard. This is not too different to the XML example: it enables indexicality and structures formats of reference. However, while in other projects these tools are merely instrumental, or even invisible, most of the technologies that make this book possible have been not only carefully selected but also built. The technical ecology of this project is very much a milieu with its own sense of accountability, verification, and ethics. A self-hosted wiki for collaboration is not (only) an instrumental endeavor, but (mainly) a political and ethical stance. In a perhaps more complex setup, the server, the online meetings, the pads, and the CSS layouts, are ‘the collective’ that this book both is and is about.

Perhaps the clearest example of this is the series of pads, where referencing practices exist but in a highly unstructured fashion: the pads (etherpad instances) traverse the whole production process, not only for each chapter, but also for coordination, planning, and communications. The post-print practice of referencing is also manifested here, yet in more subtle forms and without specific standards. Each pad brings a communal authorship (as there are no straight ids associated with the comments) and acts as a free-floating space for lineages, a variety of ideas, authors, remembrances, and even affective elements. A highly demonic ground for referencing beyond standards.

What is more, the technical layers add their own traditions and circumventions, when we refer, reuse, and remix existing technologies. For example, the project's use of tinc, a vpn daemon played indeed a daemonic role in circumventing closed academic networks. Being tinc an open software endeavor itself, the list of contributors directs towards a long-tailed genealogy of free and voluntary labour, hosting platforms, and distributed expertise. This opens the question of how we ‘cite’ not only software, but the ethos, praxis, and economies that come with it. As stated by ooooo in an email exchange regarding radical referencing:

The references are not mere symbolic capital but also have financial repercussions and redefine labour, and these issues stay [a] complex issue to tackle in the FLOSS environments.

Both Ahmed’s strategy for inclusion, and our negotiated relation to authorship and communal authorship, are traversed by these infrastructures and traditions, which enrich and complicate how we integrate production. On the one hand, we play with the demonic inherent to any technological system by choosing a certain ecology of systems that prioritizes care, openness, transparency, and collaboration (e.g., Calibre, Zotero, the wiki format for referencing, and the pad). On the other hand, we are aware of the perhaps inevitable ways in which larger infrastructures capture our labour as a community of authors and practitioners.

Unconsensual indexing

Embedded in networks, referencing takes place under a condition of general indexicality. If we index others (by referencing them), we are also indexed. In that way, technical infrastructures for collaboration, even if resilient, are not immune to un-consensual indexing enterprises, due to their capturable nature. There are multiple frames of reference for indexing, but the largest indexing operation is performed by search engines. Exposed to the scrapers of the likes of Google or Bing, words published online are ranked and indexed. This is the main condition through which digital texts are searchable. In this sense, the condition of referentiality cannot be limited to an economy of citations. It is also an economy of links. To the difficulty of formalizing a citational politics and its problematic assignation of names, we need to add the difficulty of formalizing a politics of the integration of our texts in a politics of search engine discovery and ranking. Once the document you are reading now circulates as a PDF with active links or as a wiki page, it condenses a network of references redirecting to other (bound) objects.

As an example, the wiki is a digital platform where the indexicality of the content is embedded. By using this system as a writing infrastructure, referencing can be automated and aggregated, allowing automated tools to extract and monitor the ecology and sociometrics of an article. Studies of Wikipedia can monitor and millions of references to understand the dynamics and temporal evolution of included bibliographic content,[29] and compare it to other knowledge reservoirs. Interestingly, only 2% of all the Wikipedia sources (with DOI) are indexed in the Web of Science[30] repository, showing how vastly different these two academic spaces are, just in terms of sources and validation. These are but a few examples of the index-capture relationship inherent to computational platforms, whether we talk about the neoliberal subject and the corporate software, or collaborative and open alternatives. While this allows for a better understanding of citation, trends, and knowledge in collaborative systems, embedded indexicality is also the cornerstone for highly unconsensual extractive practices.

In recent years, this condition of general indexicality created the basis for another form of textual production that culminated with the chatbots of generative AI. Indexed texts became components of datasets. Interestingly, they undergo a different process. The search engine outputs links which connect a query to an actual page whereas the chatbot mostly absorbs the referent. Here to be exposed to scrapers means being digested into a statistical model that cannot reliably refer back to its constituent pieces. To expose one’s content to scrapers means to participate (unwillingly maybe) to the production of a mode of enunciation that is controlled by those who have the means to train AI models at scale (what Celia Lury has referred to as an ‘epistemic infrastructure’, as mentioned in the introduction to this chapter). In that case, writing robots.txt files becomes an essential part of a practice of referencing as much as a list of references or footnotes. And a reminder that looking for a position regarding referencing also implies looking for versatile modes of opacity.

Intimate spaces

Referencing as conceived in this book is not about metrics and exposure only. Perhaps quite the contrary, the wiki (the vpn, the server, etc) where it rests, is more of an intimate space. As such, we can ask: what do our technical interfaces (the ServPub cognitive assemblage) allow for, that more scholastic bibliography and conventional academic akribeia do not? If there is no space in Chicago, MLA or APA for an affective dimension, the collective elaboration of this publication needs an approach of referencing that allows for the expression of admiration or tension.

Approaches to a more affective approach to bibliographic production also state both the importance of a community of care and shedding more light into the emotional work associated with the labour of academic written production, as noted by Malcom Noble and Sara Pyke. While opening the space for queering textual representation, Malcom Noble and Sara Pyke organized a gathering dedicated to discussing queer tools, methods, and practices with bibliographers. Queer Critical Bibliography, notably, does not entail only a topical gathering, but also emphasizes the intersectionality of the "academic" and the "practitioner", alongside the "emotional nature of queer bibliographic work".[31]

This emphasis on the tools for emotional labour also has wider implications. For instance, if formats are not simply thought of as practical templates, how can they be invested with other energies? Erik Satie, the composer, was aware of the limitations of formatting. His music sheets, filled with notes for the performer, deviate from the expected notation (e.g., ‘pianissimo’), and instead take a sort of emotional and highly specific instructions: "Tough as the devil", "Alone for an instant. So that you obtain a hollow", "The monkey dances this air gracefully" or "If necessary, you can finish here."[32] While there is a dadaist humor tinge in this example, Satie's scores break with the format, even in the form of annotations, of classical music, and allow for unconventional references. Perhaps in a similar fashion, the format for referencing has to represent better the practices of referencing. Ones that reflect intersectionality, collectivism, solidarity, and invisible lineages.

To summarise, this book started with the desire to publish in solidarity with others. In echo, we end by addressing the problem of referencing in solidarity. The question of referencing has led us to consider how referencing is not simply a list of sources, but a practice that can be considered in ‘radical’ and ‘autonomous’ ways. We have tried to outline what this means and the complex implications of this, also when it comes to the underlying dependencies on tools, software, infrastructures and affective labour.

One needs to understand that academic referencing, or akribeia as we have referred to it, also expresses a form of solidarity, but a very different one that underlines the ethical and almost religious undertone of academic accuracy, accreditation and authority. A style of referencing is a technical and organizational epistemic infrastructuring that reflects the ways academia indexes knowledge in order to build authority. This authority may be of an emerging field or a publication system, but also of other authorities, such as gendered, social, or racial ones. How does one build and ‘infrastructure’ other forms of solidarity?

Of course, one can choose to question and unlearn one’s own routines of referencing (and their compulsive gendered, racial or other preferences). However, an objective has also been to question the underlying principles of referencing on which all writing relies; that is, to reference in recognition of more affective and situational relations, to point out a commonality in writing and in the tools for writing that serves as a shared set of ‘demonic’ conditions where ownership of meaning and authority is less defined. To paraphrase ourselves and Jeanne van Heeswijk, to explore what a ‘potato style of referencing’ might be in an academic text that is otherwise dependent on a Chicago Manual Style. Therefore, radical and autonomous referencing within this project also includes a criticism of the power structures embedded in bibliographical conventions such as the Chicago style, of the role of authorship within a neoliberal political economy of publications, and of the infrastructures that mediate and regulate new digital formats of old traditions. That is, a political stance which is not limited to topicality within library studies that conventionally takes care of the practices and tools of referencing.

Finally, we have also considered the tools and technical infrastructures for radical and autonomous referencing, and how they are built into the ways referencing is practiced. On the one hand, the technical ecology of this project unfolds as a living milieu, self-built with its own accountability and ethics. The self-hosted wiki, pads, CSS Layout, and so on, far from being a mere tool, are a quiet declaration of political intent. Yet, one should also consider how this form of referencing and indexicality that lies within these tools inevitably are also part of a much wider one – a more general indexicality that nowadays underlines the textual production of both search engines, chatbots, generative AI, and the like. Choose your referencing and its dependencies carefully.

- ↑ Celia Lury, Problem Spaces: How and Why Methodology Matters (John Wiley & Sons, 2020), 3.

- ↑ ooooo continues: “they organize concerts, experimental audio formats and collaborate on listening performances and collective listening settings. aio works as freelance graphic designer focusing on sound related projects, small editions and art books and give weekly risography-print-workshops. they are deeply interested in questions concerning “ethics of listening” – in socio-political, environmental, embodied and queer practices of listening within its situated contexts, emancipatory possibilities within the sonic realm, forms of non-verbal communication/improvisation and relational composition. aio frei is co-founder of oor records/oor saloon. oor records is a collective, cooperative and honorary operated record and art bookstore, organic archive and social gathering place for engaged ears.oor records they were invited in the Slamposium of Mothers & Daughters, A Lesbian* and Trans* Bar in Brussles. The event took place in 15–16.10.2021, Kaaistudios. https://kaaitheater.be/en/agenda/21-22/slamposium We met after § years not seeing each other. In the after conversation of the performance A.Frei coined the term.”

- ↑ The group has operated since 2004 but terminated its activities in 2017.

- ↑ Melissa Morrone and Lia Friedman, "Radical Reference: Socially Responsible Librarianship Collaborating With Community," The Reference Librarian 50, no 4 (2009): 372, https://doi.org/10.1080/02763870903267952.

- ↑ Morrone and Friedman, “Radical Reference,” 379.

- ↑ “Question: Radical Right on Campus,” Radical Reference, submitted by emk on January 13, 2005, http://radicalreference.info/node/508.

- ↑ “Bicycling Resources,” Radical Reference, submitted by MRM on April 24, 2005, http://radicalreference.info/node/508.

- ↑ Morrone and Friedman, "Radical Reference," 378-79.

- ↑ Calibre is a a free, open-source e-book management software. Some authors have, for instance, used Digital Aesthetics Research Centre’s Semi Library in the process – built on Calibre and developed in collaboration with Martino Morandi Roel Roscam Abbing. Semi Library is a library of collective readings (rather than books) used in a collective process of research, where each publication has an associated pad for collective notetaking. As such, it belongs to a wider network of shadow libraries that would include what Olga Goriunova refers to as different subject positions, such as ‘the thief’, ‘the pirate’, ‘the meta librarian’, ‘the public custodian’, ‘the general librarian’, ‘the underground librarian’, 'the postmodern curator of the avant-garde', and more. (Olga Goriunova, "Uploading Our Libraries: The Subjects of Art and Knowledge Commons," in Aesthetics of the Commons, ed. Shusha Niederberger, Cornelia Sollfrank, and Felix Stalder (Diaphanes, 2020))

- ↑ Reading through the book you realise that “we” is used in many different ways. There is the we of a participating collective, the we of all authors, and the general we. As the sentences of this chapter have been typed by the three of us, the 'we' mainly refers to us Christian, Pablo, and Nicolas. Yet this chapter is also about complicating the understanding of this we. It has been written in dialogue with the other authors of this book. And through the various forms of referencing we discuss, many other voices are spectrally present in this we. The trio behind this we is therefore continuously expanding in the various collectives that made this book possible.

- ↑ William Rhys Roberts, “References to Plato in Aristotle's Rhetoric,” Classical Philology 19, no. 4 (Oct., 1924): 344, https://doi.org/10.1086/360610.

- ↑ ‘Akribeia’ is Greek (ἀκριβής) and means exactness, precession, or strict accuracy. It is often used in a religious sense, to refer to the accordance with religious guidelines, found in the Acts of the Apostles in the Bible, where Paul says: “"I am a Jew, born in Tarsus in Cilicia, but brought up in this city, educated at the feet of Gamaliel according to the strict manner [akribeian, ἀκρίβειαν] of the law of our fathers, being zealous for God as all of you are this day.” (Acts 22:3). In some research guidelines the notion is used to describe “academic acribia” (such as the PhD Guidelines from Aarhus University ("Guidelines and framework for the preparation of PhD recommendations at the Faculty of Arts, Aarhus University," Aarhus University, accessed January 7, 2026, https://phd.arts.au.dk/fileadmin/phd.arts.au.dk/AR/Forms_and_templates/Ph.d.-afhandlingen/Guidelines_Recommendations.pdf.)

- ↑ “About the Chicago Manual of Style,” The Chicago Manual of Style, accessed September 26, 2025, https://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/help-tools/about.html.

- ↑ Johanne Severinsen and Lise Ekern (updated by Ingrid Torp), ”The Vancouver Recommendations,” The Norwegian National Research Ethics Committees, last modified August 10, 2020, https://www.forskningsetikk.no/en/resources/the-research-ethics-library/legal-statutes-and-guidelines/the-vancouver-recommendations/.

- ↑ Severinsen, Ekern (and Torp), ”The Vancouver Recommendations,” 2020.

- ↑ Brad Wray, “Should What Happened in Vancouver Stay in Vancouver?” AIAS Seminar, Aarhus Institute of Advanced Studies, Aarhus University, September 25, 2025, https://aias.au.dk/events/show/artikel/aias-seminar-brad-wray.

- ↑ Roland Barthes, "The Death of the Author," in Image Music Text, trans. Stephen Heath (Hill & Wang, 1977), 146.

- ↑ Christian Ulrik Andersen and Geoff Cox, "Editorial: Feeling, Failure, Fallacies," A Peer-Reviewed Journal About Machine Feeling 8, no. 1 (2019): 5, https://doi.org/10.7146/aprja.v8i1.115409.

- ↑ Katherine McKittrick, “Footnotes, (Books and Papers Scattered about the Floor),” in Dear Science and Other Stories (Duke University Press, 2021), 22, https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478012573-002.

- ↑ Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds. Black Women And The Cartographies Of Struggle (University of Minnesota Press, 2006), xiv.

- ↑ https://wiki4print.servpub.net/index.php?title=Main_Page

- ↑ https://cc.vvvvvvaria.org/wiki/Wiki-to-print

- ↑ https://github.com/hackersanddesigners/wiki2print

- ↑ https://titipi.org/wiki/index.php/Wiki-to-pdf

- ↑ https://cc.vvvvvvaria.org/wiki/Wiki-to-print

- ↑ https://wiki4print.servpub.net/index.php?title=Docs:00_Contents

- ↑ The notions of 'restricted' and 'genera'l economies are found in the works of Georges Bataille (see: Christian Ulrik Andersen and Geoff Cox, "Excessive Research - Editorial," A Peer-Reviewed Journal About Excessive Research 5, no. 1 (2016), https://doi.org/10.7146/aprja.v5i1.116035.)

- ↑ Katherine N. Hayles, Postprint: Books and Becoming Computational (Columbia University Press, 2020), https://doi.org/10.7312/hayl19824.

- ↑ Olga Zagovora, Roberto Ulloa, Katrin Weller, and Fabian Flöck, "'I Updated the <ref>': The Evolution of References in the English Wikipedia and the Implications for Altmetrics," Quantitative Science Studies 3, no. 1 (2022), https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00171.

- ↑ Harshdeep Singh, Robert West, and Giovanni Colavizza, "Wikipedia Citations: A Comprehensive Data Set of Citations with Identifiers Extracted from English Wikipedia," Quantitative Science Studies 2, no. 1 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00105.

- ↑ Malcolm Noble, and Sarah Pyke, "A Bibliographic Gathering: Reflecting on “Queer Bibliography: Tools, Methods, Practices, Approaches,”’ The Journal of Electronic Publishing 28, no. 1 (2025): 254, https://doi.org/10.3998/jep.6034.

- ↑ While the literature on this is scarce, some of these examples can be found in: Vincent Lajoinie, Erik Satie (L’Age d’homme, 1985).